| INTRODUCTION

The Kurds, Cinderella of liberation movements

by Helga Graham

The Kurdish problem - or rather panorama of problems - is the Cinderella of Third World liberation movements, the issue that forever falls off the bottom of the Western liberal agenda, the 'cause' that never quite comes into fashion, like the mid-calf skirt.

Yet the Kurds are a people of 25 million. Their homeland stretches from the Taurus Mountains in the west to the Iranian plateau in the east, and from Mt Ararat in the north to the plains of Mesopotamia in the south - an area, at around 500,000 sq. km, as large as France. This land between the Soviet border and the oil-rich countries of the Arab/Persian Gulf is situated in one of the world's most sensitive strategic areas. Here is the core of the problem. The Kurds' aspirations for self-expression, human rights and economic and social development, elsewhere regarded as legitimate and even laudable, are seen to collide with a Middle Eastern status quo that has acquired the standing of a totem.

This situation is inherently unstable as well as unjust. It is neither possible nor practicable for the Western powers which have so much influence on the area - whether financial, technological Or military – to encourage freedom, human rights and democracy for Eastern Europe, while aiding and abetting regimes which deny such rights to their citizens. Admittedly, the Kurds' problem in this respect is greater than that of most other peoples in the Middle East since the post-First World War settlement denied them a state of their own. Ultimately, however, the Kurds' future, as that of their neighbours, depends on the development of democracy in the area generally, and their capacity to forge alliances with the new middle classes who have aspirations similar to their own. No doubt guerrilla activity will, in some form and for some time, remain a constant of Kurdishness. But in the face of modern weaponry - as Iraqi Kurds have recently realized at terrible cost - traditional Kurdish modes of political operation are of diminishing relevance and efficacy. Like the early Middle Eastern traders who used the monsoon winds to carry them to distant El Dorados, the Kurds must keep a weather eye on and use the prevailing political winds in the region. They must bear in mind that in a new world governed by the principles of interdependence and reciprocity, their future is inexorably linked with that of the other peoples living around them whatever the precise shape of the political institutions that eventually crystallize. In shaping these, the temptation is obviously to compensate for the past; but the challenge will be to discover the dominant trends in the coming decades and to go with the grain, whatever it may be.

Nowadays the Kurds must also learn to wage a different kind of war from the ones they have known so far. This is the information and public relations battle. The average Westerner, even someone with a minimal knowledge of the Middle East and a maximum of liberal good-will, is simply unaware who the Kurdish people are and where they come from. The Kurds' efforts to achieve a fair hearing are defeated as much by our invincible ignorance in the West as by vested interests.

My own awakening to the issue came about as a result of personal involvement when I was asked to make a film in Iranian Kurdistan in the early 1980s. The Ayatollah Khomeini, having initially given Iranian Kurdish leaders, to understand that he was sympathetic to their demands for democracy and autonomy in Iran, soon reneged, and the Kurds responded by erupting in rebellion. When I visited Iranian Kurdistan a full-scale guerrilla war was being waged amid the magnificent mountains of western Iran. The filming operation was to record this struggle from the point of view of the Iranian Kurds, led by Dr Abdolrahman Ghassemlou, a witty and sophisticated tribal leader and Paris-trained intellectual (who was recently gunned down by Iranians in Vienna). The Iraqi government, locked in mortal combat with Iran, was happy to let the film crew enter Iran illegally across the high, wild no-man's-land that separates the two countries in the north.

The Kurdish mountains, even in the winter,, even in war, are unforgettably beautiful: a land of silver-streaked turquoise streams, bordered by golden autumn aspens, snaking along precipitous valley floors; women walking to wells for water in gorgeous coloured brocades of rich plum, vermilion, crimson, cream and gold, like figures from an Elizabethan pageant, flitting between broad-girthed oaks peppered with the first snow. The stars, at night, were crowded so close it seemed possible to reach out and touch them.

But it was the Kurdish people themselves who made the deepest impression. The vitality and courage of the young Kurdish guerrillas sharing the small village houses where we spent nights, partying into the dawn (or until, fretful for sleep, we stopped them) on a glass of tea and a handful of walnuts, despite or perhaps because they would risk death again on the next day. The Kurdish term Peshmerga (used for the Kurdish resistance fighters) means 'those who face death'. And these guerrillas communicated a deep sense of moral purpose, solemn, heroic after the manner of some distant age, long gone, some ancient medieval chivalrous order. Saladin was a Kurd; and one often felt that the best of both sides during the Crusades, those who were fighting the holy war of chivalry rather than merely bootlegging, must have been very like these high-minded young men with their startling ethos of self-sacrifice and their thin, inadequate plastic shoes amid the infamous winter cold. Despite the terrible so-called dum-dum bullets (which explode under the skin) used against them by Khomeini's forces, Ghassemlou's men refused to respond in kind - just as Iraqi Kurds do not torture prisoners, even to extract vital information, although Saddam Hussein's regime routinely employs grotesque tortures against them. Given the Kurds' circumstances, these are moral achievements of a high order.

On a mountain path one day, we met a guerrilla with an English novel nestling in his cummerbund next to his revolver. He showed no self-pity despite ten years spent in the Shah of Iran's prisons, paying the price Kurds have to pay everywhere, it seems, for their stubborn insistence on freedom. Could I send him a recent novel from London? A friend of his in Iraqi Kurdistan, he said thoughtfully, had had the Manchester Guardian delivered to his distant mountain top.

A rare, perhaps unique occurrence... One which also points up another of the many difficulties the Kurds have to face in making their case known. Despite the desultory drift to cities in recent years, the Kurds are still primarily a peasant people with a relatively small intellectual class. Today they are still fighting their way out of a cocoon of tribal loyalty and are only gradually emerging from a world where each valley is another country.

Hence the interest of Sheri Laizer's book. There are few enough attempts to analyse the Kurds' political predicament (which is to some extent of the West's - Britain and France's - making). But there are even fewer attempts to describe who the Kurds are as a people, and how they live.

Ms Laizer knows particularly well, from personal experience, the Kurdish areas of eastern Turkey - the so-called 'sleeping giant' of Kurdistan, an area with a population of between 8 and 10 million. Here possession of a single cassette by Kurdish singers can mean six months in prison - or, as she writes laconically, worse.

Ms Laizer paints vivid vignettes of daily life: the ritual of women in the communal Turkish bath, the shepherds with their fearless, knowing faces 'granting respect only to nature's laws and harshnesses', a Kurdish grandmother's first spirited encounter with television, a concert by a 'suspect' Kurdish singer in Istanbul, Kurds taking part in a festival to celebrate the Turkish Republic's victory over the European imperialist powers. She writes a moving account of this occasion:

I felt very fortunate in being able to see them all gathered there in their vividness and variety, for once in a situation where enjoyment was permitted overt expression... Obviously delighted to have a lawful occasion for appearing in this fashion, they flashed looks of silent triumph and power at friends scattered throughout the crowd.

For once, 'enjoyment permitted'. This says it all.

'We follow Sheri Laizer's journey into a culture very different from her own - a journey through friendships, acceptance and marriage, from the outside to the inside. It is impossible not to be moved by this extraordinary account of this proud, passionate and resilient people.'

Peter Gabriel

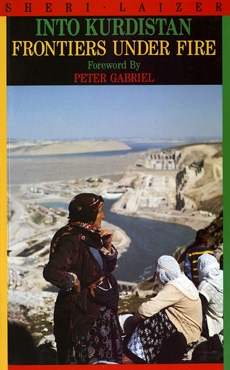

Into Kurdistan is a journey through the lives of a people without a country. Part travelogue and part political commentary, it portrays both the pride and the oppression of the Kurdish people.

Sheri Laizer recounts the drama of a family living close to the border, hearing gunshots and wondering if a favoured son will make it home at night from a smuggling expedition. She shares the companionship of Kurdish women in the mountains, washing in the melted snow. She captures the ambiguity of Kurdish intellectuals entwined in the cultural life of Turkey, a country which refuses to acknowledge the very existence of a Kurdish identity. And she paints a vivid picture of the centuries of tradition behind the people who had given the Middle East some of its greatest heroes, from Saladin onwards.

Into Kurdistan uncovers the recent atrocities in Iraq, and the systematic persecution suffered by the Kurds in Turkey. In a marvellous blend of political commentary, folktale and sympathetic observation, Sheri Laizer helps us understand the people behind the terrible headlines.

'The best introduction we have yet to the life of the

average Kurdish citizen of Turkey.'

Hazhir Teimourian, Middle East specialist of

‘The Times’.

'Ms Laizer paints vivid vignettes of daily life.'

Helga Graham

'Part travelogue, part political history... Laizer's personal approach brings the cold statistics and blunt facts of newspaper headlines to life.'

Geographical Magazine

|