| Éditeur : Oxford University Press | Date & Lieu : 1936, London |

| Préface : | Pages : 340 |

| Traduction : | ISBN : |

| Langue : Anglais | Format : 155x230 mm |

| Code FIKP : Liv. Ang. 3651.I | Thème : Histoire |

|

Présentation

|

Table des Matières | Introduction | Identité | ||

Versions:

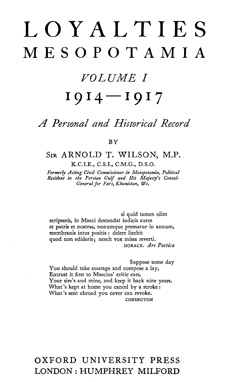

Loyalties Mesopotamia, volume 1 | |||||

|

PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION Five years have elapsed since I wrote Loyalties and its sequel The Clash of Loyalties, which are here reproduced without alteration or omission. There is no word in the prefaces, and little or nothing of substance in the body of either volume which I should wish to omit, or to say otherwise. The events of the past six years have served rather to emphasize than to dispel the doubts here recorded as to the wisdom of the decisions reached at Versailles and later, in regard to Turkey, at Lausanne. The fears expressed as to the fate of the Assyrian minority whom we abandoned, after using them for our own purposes, have been confirmed by the terrible events of 1934, and by the palsied indifference or helplessness of Great Britain and France. Many hundreds were massacred in cold blood by Iraqi troops within a few miles of a squadron of the Royal Air Force in defiance of assurances which we gave to the League of Nations, who would not have been content with the formal undertakings of the Iraq Government had they not been endorsed by us. We did not withdraw our Ambassador: we did not even permit British Military officers serving in that country as a Military Mission to return, as they desired, to England. The question as to the future settlement of the Assyrians was 'referred to the League': two years have elapsed, and nothing has been done. We have broken our word, pledged at Geneva to these people: the whole Moslem world is aware of the fact and discount, accordingly, the sincerity of our representatives at Geneva when they speak of the sanctity of treaties. The French Government have declared their intention to abandon the mandate for Upper Syria, whilst maintaining a firm hold over the Lebanon. This decision is probably wise. Nothing has happened in Syria in the past five years to cause me to modify the opinion expressed at page 11 of vol. ii, that the mandatory principle in Syria was unworthy and did not deserve to endure. The removal or restriction of French authority in Northern Syria will sooner or later have grave consequences in Southern Syria which, under the name of Palestine, is a British responsibility under the form of a mandate. Events in Palestine in the last five years have given point to the statement, with which I concluded the first volume (p. 306), that 'to the Jewish and to the Christian population of Arabia, as well as to the Arabs, the policies of the Allies (viz, in Syria and Palestine) involved a sharp conflict of loyalties, the issue of which is still in doubt'. Although British statesmen had for half a century been acutely aware of the difficulties inherent in the existence within the Turkish Empire of large religious and racial minorities, we proceeded of our own volition, though of course in our own temporary interests, to pledge ourselves to create a fresh and formidable minority problem in almost the only part of Turkey, and the only part of Syria, where minorities had not already been a cause of war and massacre. The Balfour declaration (for text, see vol. i, p. 3o5) had two sides: we have emphasized that of the Jewish national home, with less regard to the equally solemn pledge to respect Arab rights. We never intended, and the Arabs were never led by us to expect, to see nearly half a million European Jews in Palestine 15 years later, the vast majority being our former enemies from Central and Eastern Europe, not Semitic by race (being mainly converted Slays), wholly unassimilable and Jewish by tradition and temperament rather than by race. The Poles, who form the majority, have left Poland not because they are persecuted, but to better themselves. Some 50,000 Poles, if dependents and clandestine immigrants be included, entered Palestine in 1935. That is about the net annual increase of the Jewish population in Poland, and Palestine clearly cannot long continue to absorb so many. Zionism is no sort of solution of the Jewish problem; it is scarcely even a serious contribution to a solution, but it is bound to have a serious effect upon the minds of Arabs in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. In the last five years, under despotic rulers drawing their strength from the people with whose assent they rule, Turkey and Persia have become stronger, from every point of view. They are no longer elements of weakness in the Near and Middle East; they display a strength and unity of purpose which contrasts with the uncertainty and infirmity of purpose which has marked the policies of Western parliamentary democracies for some years past. If the German demand for the return of certain African mandated territories is accepted, as is ultimately probable, it is possible that Turkey, now renewing her youth, will renew her ambitions. Of such a tendency there is no sign at present, but the whole course of history suggests that powerful and united nations are adscititious, and tend to absorb weaker units on their borders, as Russia has done during the past fifteen years. Arabs are by disposition fissiparous-'a people of dissension', ahl al nifaq' in their own proverbial lore, agreeing only to disagree. The course of events must be measured not by calendar years but by generations. Turkey, secure behind the Dardanelles, can afford to await the Day: she will be assisted by the rapid weakening of Islamic feeling and the growth in its place of xenophobia, directed principally against Europeans and greatly stimulated by our Zionist commitment, which is the antithesis of the popular gospel of self-determination. Only one new factor has emerged in the last five years, namely, the discovery and development, on a great scale, of the oil-fields of Iraq, and the completion of pipelines carrying the crude petroleum from the Eastern side of Northern Iraq to Tripoli and Haifa. British, American, French, and Dutch capital aggregating many millions of pounds in-vested therein is now concerned in the maintenance of order, and the governments of Iraq, Syria, and Palestine are alike, though not equally, interested in preventing any disturbance which might hamper the operations so mutually profitable to all concerned. This is perhaps the most hopeful feature of the present situation. It will retard, but will not prevent, great political changes: it will provide in the future, as now, substantial revenues to de facto or de jure governments. How difficult it is to forecast future developments may be gathered from the fact that the one man who emerged during the war and has since strengthened his position -Ibn Saud- was regarded by such authorities as the late T. E. Lawrence and D. G. Hogarth as unworthy of their attention and as unlikely to attain power. The only certainty is that the present state of affairs in Iraq and in the Middle East generally, elsewhere than in Turkey and Persia, is unstable; the existing regimes transitory. Improved communications have not allayed but increased national and local rivalries: extended facilities for superficial education have enhanced the ambitions and jealousies of those who aspire to administrative and executive offices in these countries. None of these movements have yet reached their full development: when they have done so, perhaps a decade hence, the reaction will begin. It will gain strength from the growing resentment of the toiling masses, cultivators, artisans, and shepherds, who have little of the bitter, narrow patriotism which, however artificially fostered, inspires the college-bred scions of the middle and upper classes. I am inclined to believe that, mindful of their long history, they will turn to Turkey, as twenty years ago they turned to Great Britain, in the hope that, as part of a larger whole, they may be rid of `servants upon horses, and princes walking as servants upon the earth'-a spectacle as little pleasing to wise men now as to the writer of Ecclesiastes. For the rest, I respectfully commend this book in its new form to a larger circle of readers who may here read what their fathers and brothers endured and suffered, in bitter cold and torrid heat, emerging from the furnace of affliction neither bitter nor resentful, neither hard nor broken, but cheerful and patient, and able on return to civil life to play a dignified and useful part in the life of their country which sent them out. They-the rank-and-file-left behind them a reputation which no foreign army has ever enjoyed in eastern countries: they did more for our good name than the greatest ambassador. 'They were a wall unto us by night and by day' and their Indian fellow soldiers were, as these pages show, not inferior in discipline, in endurance, or in courage. All alike possessed what we most need today; faith in the nation; hope for the future, and charity towards, or love of, their fellow men. To the memory of my dearest friends who perished in Iraq, and to the memory of the great company of 60,000 men who died there, I again dedicate this work. Arnold Wilson Lammas Day, 1936. PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION In the four months that have elapsed since the publication of this work in December 1930, it has been widely reviewed, and I have been privileged to receive more than a hundred letters from men who participated in or had personal knowledge of the events described. Their criticisms are summarized in the following notes. Except as stated below, no responsible critic has as yet questioned either the facts or the conclusions reached. The argumentum ab silentio is always weak, and I should be the last to claim that my interpretation of this tangled chapter of our history, which in places is inevitably controversial, cannot be challenged by some men whose knowledge of particular aspects of the campaign is greater by far than my own. It is, however, perhaps legitimate to deduce there from that the narrative, in its broad lines, has stood the test of contemporary criticism. A. T. W. Saint George's day, 1931 Notes - page 10, note 2. The name of the fourth ship was the Jaffari, owned by a resident of Basra, Agha J'afar. - Page 82, The following is an extract from Sir George Arthur's Life of Lord Kitchener (1920), vol. iii, p. 301: 'The situation which the War Secretary and the Chief of the Staff had to consider at the close of 1915 was none too rosy. In October the War Committee-called at that time the Dardanelles Committee-inspired by the India Office, had decided that General Nixon should be ordered to march on Baghdad with the force at his disposal, two divisions being promised him as soon as possible. Kitchener dissented, decidedly but vainly, from this mandate; he even repaired to the Secretary of State for India and warned him that he considered the advance, without further preparation and a larger force, to be fraught with danger; urging that anyhow it could be made with less risk, less cost, and equal value later on. Lord Curzon was wholly of the same opinion, and even negatived a suggestion of Kitchener's that a raid might be made on Baghdad to secure any valuable military stores there without permanent military occupation. The Committee, however, after consulting the Viceroy, overruled the main joint objection of the two members who had first-hand and first-rate knowledge of the East.' Sir Austen Chamberlain in a letter dated March 11th, 1931, makes the following comment, which with his permission I reproduce below. 'This paragraph is misleading. The story is fully told in the Official History of the war by General Moberly, vol. ii, chapter 13, and in the Report of the Mesopotamia Commission. 'The India Office did not initiate or, to use Sir George Arthur's words, "inspire" the advance to Baghdad. On the contrary, on receipt of General Nixon's telegram stating that he proposed to concentrate on Azizaya with the intention of opening the road to Baghdad, the Secretary of State, on the advice of General Barrow, Secretary in the Military Department, telegraphed that it seemed imperative to stop General Nixon's further advance, and added that the previous orders as to a cautious policy in Mesopotamia held good. 'The ultimate decision to advance was taken by the War Committee and Cabinet only after it had been decided to reinforce General Nixon with two divisions, and in accordance with the expert opinion of all the military advisers which is thus summarized by the Mesopotamia Commission: "Expert opinion was therefore unanimous on the point that to attempt to take and occupy Baghdad with the existing force would be an unjustifiable risk, and that for the task of holding Baghdad, General Nixon should have a reinforcement of two divisions. There was, however, a concurrence of expert opinion that Nixon's existing force was sufficient in the first instance to take Baghdad."' (Paragraph 20) 1 My italics. 'Lord Kitchener never expressed any doubt of General Nixon's ability to seize Baghdad. He was anxious about the position in Egypt, reluctant to send the reinforcements ordered by the Cabinet, and desirous of confining the operations to a raid effected with the object of seizing whatever military stores were in Baghdad. 'To this suggestion Lord Curzon was at least as strongly opposed as to an occupation. Kitchener, on the other hand, argued that not to move forward and to seize what was practically in our grasp would make all the local population think that we were afraid to do it, and that if we moved back from our position without going to Baghdad it would be quite as bad as to withdraw after a raid on the city. 'The correspondence which passed between Lord Kitchener and the Secretary of State is summarized in the Official History. Lord Kitchener's subsequent visit had for its object to persuade the Secretary of State to send a telegram which in the latter's opinion was incompatible with the Cabinet's decision. Mr. Chamberlain declined to do this on his own responsibility, but said that he would gladly hold up the instructions if Lord Kitchener would again bring the matter before the Cabinet. This offer was declined by Lord Kitchener, and the Secretary of State then repeated that it was impossible that he should reverse a Cabinet decision at the request of a single colleague, but that he would ask for an immediate meeting of the Cabinet to hear Lord Kitchener's views. Lord Kitchener refused his assent to this proposal and declined to have the matter reopened in Cabinet. '11th March 1931.' / A. C. - Page 83, para. 3. This telegram was based on information supplied to the India Office by E. B. Soane, who made good use of his eyes and ears whilst on his way to Mesina from Baghdad. - Page 123. In my criticism of the action of the 21st Brigade I have followed the `Critical Study', p. 209. An officer of this Brigade writes to me under date March 13th as follows: 'As I read your description, no part in the attack was taken by the 21st Brigade, which is not correct. I was with machine guns in the front line when the attack took place, and I was with the Norfolk-Dorset Composite Battalion of the 21st Brigade when they went over the top on the launching of the attack. I was also with Colonel Case in the front line when the Division was compelled to retire owing to the abandoned, water-logged trenches in No-man's Land. The composite Scottish Battalion (Seaforths and Black Watch), the 92nd Punjabis, and the Norfolk-Dorset Composite Battalion all came back together, and Case went out to try to rally his men. When he got amongst them they were all mixed up with the 92nd Punjabis and the Scots, and it was clear to him that they could not stay where they were and they all came back together in rather a hurry.' - Page 130, para. 3. Since these lines were written, as the result of a Conference convened by the Swiss Federal Council, two Conventions dealing respectively with the Treatment of Prisoners of War, and with the amelioration of the condition of the wounded and sick in armies in the field, have been concluded, and laid before Parliament (Cmd. 3793 and Cmd. 3794-1931) pending ratification, for which, in the former case, legislation will be necessary. Both Conventions represent a notable advance. The Conference made the following important recommendations (Cmd. 3795) (I) that the question be examined whether fresh safeguards lasting until the end of their treatment in hospital could not be established for the benefit of persons who are badly wounded or seriously ill and have fallen into the hands of the enemy. (2) that an exhaustive study should be made with a view to the conclusion of an international Convention regarding the condition and protection of civilians of enemy nationality in the territory of a belligerent or in territory occupied by a belligerent. - Page 18 I. Sir John Fortescue writes as follows: 'The Walcheren Expedition, though its conduct was on many grounds condemnable, was by no means such a wild project as the Mesopotamia Expedition. It was not unsound in conception; it set Fouché wondering whether he would not head a rebellion, and it gave Napoleon one of the worst frights of his life. The words of such a petty politician as Francis Burdett are really not worth quoting, and Kinglake's comment at the foot of p. 18I is sheer drivel.' I respectfully agree. - Page 203, para. 2. I am informed that the change was not complete until after the Armistice. - Page 240, line 23. I owe General Hawker an apology. He was well acquainted with Arabic. - Page 273, line 5. There was no engagement at Huwaislat. - Page 275, para. 3. General Hawker comments as follows: 'The Jewish community wished to give a theatrical entertainment and invited British officers to it. They asked to be allowed to offer refreshments during the entracte. I consulted the medical authorities, and it was decided that only Turkish coffee was to be offered. The day before the entertainment my Staff Captain, Payne, died of cholera. I went to his funeral on the day of the Jewish entertainment, and so did not go to the performance. 'General Maude was offered a small cup of coffee. He asked for a bigger cup and then asked for milk. No milk was available, and so the people who were offering the coffee sent out hurriedly for milk and a bottle was fetched. It is a well known rule and custom in Turkey and Arabia that no milk is offered with coffee. 'After General Maude died, maps of transparent paper were made showing where cases of cholera were occurring, and it came to light that groups of cholera cases on different maps showing Civil and Military cases, exactly fitted over the spot where the milk was fetched from. 'Turkish coffee was allowed to be offered because it is boiled up three times, and this eliminates danger of cholera. | ||||