|

PREFACE

By Dr. Jose Ramos-Horta

Across the globe, ethnic groups are rising up to fight for their right to self-determination. Inspired by present-day Western democracies and Western revolutions of the past, peoples of the Third World are striving to free themselves from the oppression of regimes who prevent them from exercising their basic human rights of free speech and self-rule. In my own country of East Timor we are very aware of this issue; for 21 years we have been struggling against a brutal occupation by the Indonesian government and army, who denies our demand for self-determination.

A no less critical struggle is being waged in the Kurdish provinces of southeastern Turkey. There, 15 million Kurds face cultural, social and political oppression from the Turkish government. In response to this oppression, many Kurds have taken up arms as part of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), while others have chosen to fight the battle more peacefully, through the formation of political parties.

The Turkish government has allowed the military and political opposition no breathing space. Since 1984, the Turkish military has conducted an all-out assault against the PKK, and in the process, has burned more than 3,000 villages and displaced more than 3 million Kurdish civilians. The Turkish government has also worked consistently to undermine all attempts by the Kurds to organize politically. Pro-Kurdish political parties are repeatedly shut down by the Turkish authorities, and party members are often imprisoned for so-called ‘crimes of opinion’.

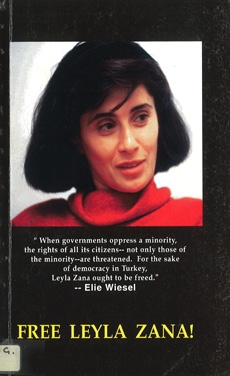

Leyla Zana, instead of joining the Kurdish guerrillas of the PKK, chose to join the political movement. Elected to the Turkish Parliament in 1991 by more than 80% of her Kurdish constituents, she became, through her attempts to represent her people, one of the most vocal critics of the Turkish government’s Kurdish policy and, as a result, was sentenced in 1994 to 15 years in prison.

Those of us who are free and able to affect change should do everything possible to set Leyla free. Leyla Zana’s error was to appeal for self-determination and respect for the rights of her people. Similarly, our East Timorese leader, Commander Xanana Gusmao, who resisted the Indonesian invasion and its unimaginable brutality, serves, as does Leyla Zana, an unjust prison sentence of 20 years. Like Mahatma Gandhi and Thomas Paine before him, we need to be guided by points of principle, rather than the politics of pragmatism. If we do not support Leyla and her cause, we risk being called hypocrites, for all of us seek, indeed demand, self-determination for ourselves and respect for our political rights.

The Turkish government promotes itself to the world as an example of a successful, secular democracy. However, it fails to mention its intolerance of the Kurds. The conflict in Kurdistan between the Turks and Kurds is not merely one people’s fight for freedom, or, in the case of Leyla Zana, one individual’s fight for freedom. The conflict in Kurdistan amounts to the subjugation of one people by another, of a minority by a majority. By ignoring such repression, the free world runs the risk of advancing the cause of intolerance worldwide.

In supporting the effort to free Leyla Zana, I am appealing for a more tolerant world, in which all political prisoners such as Leyla Zana and Xanana Gusmao are liberated, and all repressive governments such as Turkey and Indonesia are judged, not according to self-serving expediency, but according to morality. The New World Order can only be ushered in when the principle of self-determination for minorities is respected. I am glad to be part of the effort to free Leyla Zana and I invite you to do the same.

Dr. Jose Ramos-Horta is the Special Representative of the National Council of Maubere Resistance (CNRM), underground umbrella organization based in East Timor comprising all East Timorese groups opposed to Indonesia’s occupation and led by Xanana Gusmao. He is the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize Co-Laureate along with the Head of the Catholic Church of East Timor, Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo.

Preface

By Kathryn Cameron Porter

It is an honor for me to do my share to validate the message of Leyla Zana, a courageous Kurdish leader imprisoned for her peaceful advocacy of the cause of her own people.

As a woman, I feel a special kinship and mutual solidarity with Leyla Zana, the only Kurdish woman ever to serve in the Turkish Parliament. We have together fought to break through the proverbial “glass ceiling” in an effort to ensure equal rights for our daughters and our granddaughters. Unfortunately, Leyla and I differ in one significant respect. Whereas I can pursue my career as a proponent of human rights worldwide, free from oppression, Leyla Zana’s pursuit of the basic rights for her people, taken for granted in much of the world, resulted in her imprisonment in Ankara, Turkey.

Hence, Leyla Zana has come to symbolize the struggle of the Kurdish people in Turkey. She was elected to the Turkish Parliament in 1991, in the first elections in Turkey in which Kurds were allowed to participate under their own identity. But, when she sought to affirm that identity and to speak out for her people, she was arrested, prosecuted on charges of treason and sedition, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. It is analogous to Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell being arrested for raising issues relating to Native Americans in the United States Congress.

Kurds have long lived in their mountain fastness, nurturing over the millennia their distinctive language and culture. And yet, they have had the terrible misfortune to see their language, their traditions, and their freedoms trampled by powerful neighbors intent on denying their very existence.

When minorities are oppressed, they are not the only ones imperiled; democracy as a whole is imperiled. I humbly call upon all men and women of goodwill across the globe to join in the struggle for Leyla Zana’s freedom, and for recognition of the sacred right of the Kurdish people to their linguistic, cultural, and political identity within their historic homeland.

Ms. Kathryn Cameron Porter is President of the Fairfax, VA-based Human Rights Alliance, and has devoted much of her time to the plight of the Kurds and has visited Kurdistan on several occasions.

Preface

By Lord Eric Avebury

In October, 1993, I visited southeast Turkey, in the company of Leyla Zana, and got to know this extraordinary woman. As she moved among the Kurdish people, their love for her, and her ability to inspire them, were immediately apparent. As soon as she appeared in a village, crowds gathered round wanting to see and speak to her, desperately looking for comfort and hope. Some day, the panzers and the helicopters of the oppressors will leave, and the Kurdish people would have a government of their own people, people like Leyla Zana.

We saw, together, villages destroyed by the Turkish military and gendarmerie. We met the bereaved relatives of the victims of terror, and we traveled through a region occupied by a foreign army, bristling with checkpoints manned by their troops.

When Leyla Zana was inducted as a member of the Turkish Grand National Assembly, she was asked whether she spoke any foreign languages, and she replied “Yes, Turkish.” In a state where the existence of other languages and cultures has been denied since Ataturk’s National Pact of 1921, that was a brave but dangerous act of defiance. Her disrespect for the TGNA was brought up, as evidence for ' the charges leveled against her and other MPs of the pro-Kurdish Democracy Party in the State Security Court. “Terrorism,” according to the law, meant any speech or writing which might undermine the indivisible integrity of the Turkish state, republic and people. Leyla Zana incessantly and deliberately questioned the unitary structure of the Kemalist constitution, not only in the TGNA, but in discussions with the French, German and American media.

Today, Leyla Zana and her colleagues Hatip Dicle, Orhan Dogan and Selim Sadak are in Ankara State Security Closed Prison, where they are due to remain until the year 2005. Their crime was to struggle for a peaceful and democratic solution to the Kurdish question, the very existence of which is denied by the Turkish establishment. There, Leyla Zana complains that for the whole of last summer and autumn she never saw the sun. She cannot telephone her husband and her children ages 14 and 18, who live abroad. She has to share a cell with a woman convicted of murder.

The criminalisation of Parliamentary expression has been universally condemned; by the European Parliament, the Inter-Parliamentary Union, and by thousands of individual Parliamentarians throughout the world. Yet Turkey continues to enjoy the privileges of membership of international bodies such as the Council of Europe and the OSCE, which are supposed to uphold democratic standards. The Kurdish people are still deprived of their cultural and political identity, and more than three million of them have been forcibly displaced from their homes to the slums of Adana and the shanty-towns of Diyarbakir. We owe it to Leyla Zana to struggle for her freedom, and for the freedom of the Kurdish people.

Lord Eric Avebury is the Chair of the Parliamentary Human Rights Group in the House of Lords in the United Kingdom. Because of his advocacy work on behalf of the Kurds, he has become a persona non grata in Turkey.

Leyla Zana at a Glance

Leyla Zana was born in Diyarbakir, Turkish Kurdistan in 1961.

At the age of 15, she was forced to marry her father’s cousin, Mehdi Zana.

Years later, commenting on her marriage, she said:

“I don’t blame my family or my husband, rather I blame the social conditions. These must be changed.”

In October 1991, she ran for a seat in the Turkish Parliament to represent her hometown of Diyarbakir.

She received approximately 41,000 votes, or 84 % of the total vote.

She became the first Kurd to break the ban on the Kurdish language in the Turkish Parliament, for which she was later tried and convicted of treason. She had uttered the following words:

“I am taking this [constitutional] oath for the brotherhood of the Turkish and Kurdish peoples.”

On May 17, 1993, she and her colleague Ahmet Turk addressed members of the Helsinki Commission of the United States Congress. Their testimony was used against her in the court of law.

On March 2, 1994, colleagues in the Turkish Parliament revoked her constitutional immunity, paving the way for the Turkish police to arrest her.

On March 4, 1994, she was arrested and taken into custody.

On December 8, 1994, she was sentenced to a fifteen-year prison term by the Turkish State Security Court, which was composed of two civilian judges and one military judge.

Along with her, there are three other Kurdish members of the Turkish parliament, Hatip Dicle, Orhan Dogan, and Selim Sadak, who are also serving 15-year sentences on charges similar to Leyla’s.

Leyla Zana is currently in her third year at the Ankara “Closed” (sic) Prison in Ankara, Turkey.

She is the mother of two children, Ronay and Ruken, and is still married to her husband, Mehdi.

…..

|