|

PRELUDE

“When the hoary deep is roaring, and the sea is broken up with foam, and the waves rage high, then lift I mine eyes unto the earth and trees....”

Moschus, Idyll V.

I had invited the Yazidi princess to lunch with me in our house by the Tigris in Baghdad. She rang up from her hotel to reply. I said, “Who is it?” A voice replied, “Wansa; it is Wansa speaking” “Did you get my note, Mira Wansa?” “Yes, thank you very much. Madame, I will come. Madame, you are very gentle.” She had learnt some English and French in Beyrut, so what she meant was “it is very nice of you to ask me.”

This girl had been expelled from Syria. When she ran away from her husband, the ruling prince of the Yazidis, she crossed the frontier by way of the Jebel Sinjar, her real home, to shelter with co-religionists in Syria, for assassination would have been her certain portion had she stayed. At twenty-four life is sweet, although the marriage arranged by her father, Ismail Beg, had been a tragic mistake, and although she had lost her only daughter Laila as well. She spoke of her with tears in her eyes: 11 Madame, I loved her! ” Malaria, the cruse of the Kurdish foothills, claimed this little victim and so snapped the only remaining link between the young princess and her husband.

The refugee was without a passport in wartime and the French authorities were suspicious. She was placed in an hotel under military supervision, but it was pot considered advisable to allow this charming young woman, whose name was suggestively “Amusement (Wansa), to remain in the country. Considering the times, this was natural. Coming as she did from a country where nationalism takes the form of an active interest in neighbouring politics, she became the object of doubts. Finally, as “a menace to public security” “Wansa, Princesse des Ydzidis” was sent back over the frontier again and placed herself under the protection of the ‘Iraqi Government. She established herself in an hotel in Baghdad, with her mother and brother, and was far from friendless, since several schoolfellows in Beyrut, ‘Iraqi of origin, lived in that city. Whenever she goes out, however, she is guarded, for assassination lurks round the corner for her even in Baghdad, and to return to her own people would be suicide. When she came to see me, the policeman detailed to accompany her waited by the house till she came out. Yet she yearns for her hills, like that Median princess for whom the Babylonian king, her husband, built an artificial mountain, called misleadingly the Hanging Gardens.

She talked to me of her home in the Sinjar, and answered all my questions about the habits and customs of her people with an appreciation of the points which showed cultivated intelligence. She is the first Yazidi woman to be educated. Her father, Ismail, of the princely family, broke with tradition by sending her to school, and the failure of her subsequent marriage with the ruling prince, a man older than herself and himself unschooled, has led the wiseacres to shake their heads and say, “There, we said that no good would come of teaching a woman to read.”

When I first visited the Yazidis in the north eighteen years ago, practically no Yazidi boy attended school, and none but a few of the religious shaikhs could read. Education was forbidden. Now it is different. At the village of Baashika, where I spent part of April this year, many Yazidi boys attend the local Government school. A few have passed into the secondary schools, and before long there will be a supply of Yazidi schoolmasters to teach Yazidi children : indeed, there is one already in the Jebel Sinjar. The parents, mostly farmers, are not yet enthusiastic. They fear, and perhaps with reason, that if their sons go to school they will find agricultural work demeaning and will hanker, as often happens, to become clerks and petty Government officials. To remove this fear should be the task of the schools, and I hope that the Yazidi teachers, themselves not town-bred, will be able to implant in their pupils a true pride in work on the land which bred them, as well as interest in anything which may improve traditional methods of tillage. To exchange their natural heritage for the office-stool and coffee-house, for the empty life of the cffendi, would be the sorriest of bargains. Too often, enthusiastic schoolmasters see in successful examination results and office employment the goal for every scholar, no matter what his origin, with the result that the peasant lad leaves his village and becomes a drug in the towns. This is to question the fairy gold which the Little People place at the cottage door, for which the punishment is that the gold turns to black coal.

As for the girls, their time will come : meanwhile, I wonder how much these peasant women lose by not being able to write their names or read the cinema captions, accomplishments which are, too often, the only result of education in a country where a woman rarely opens or reads a book after leaving school unless she has taken up a profession. No, these Yazidi women cannot read. They cannot read the fashion papers, or news columns, or even the advertisements of patent medicines.

But they grind the grain which their men have harvested, they work in the fields, they bake, they cook, they milk, they make butter, they weave, dye, bleach, sew and wash clothes. All day and every day in Yazidi villages one hears the clop-clop of wooden clubs as they beat the family washing at the springs, great tablets of home-made olive-oil soap beside them on the stones, and garments and cloths spread on the hot rocks to dry. The washing-pools are the women’s clubs : here they gossip, and here reputations are made and lost. All this is in addition to the work of bearing and suckling children, which not a woman shirks or evades. I heard many charms for curing barrenness, but never of a contraceptive or of any spell for the prevention of child-birth.

I had intended to revisit the Yazidis for some years past, and not as a quickly passing traveller, but to stay long enough with them to know something of their daily lives and doings. In the spring of 1939 I was upon the point of starting when a rumour, started in the bazaars after the sudden accidental death of the young King Ghazi, led to trouble in the north. Anti- British feeling had long been prevalent in the schools, and in Mosul schoolboys led a rush to the British Consulate.

But a short while before, these same schoolboys had been the Consul’s guests, and it was his trust in their friendliness which led to his coming down unarmed, and to the brutal attack which killed him. It was not their fault. They believed that we had treacherously killed their king, and answered supposed treachery with treachery. The lie still lingers, for truth is too simple to be believed by a generation trained to expect intrigue from every European. It is a disadvantage to Truth in any Oriental country that she is naked. They expect her, like every decent woman, to be well covered and veiled. For this reason, plain statements of fact over the radio have little chance of being credited. Coffeehouse wiseacres shake their heads. “It is' all propaganda. Both sides have their propaganda. Both sides tell lies. It is natural.” 1

As Mosul was my jumping-off place, this unfortunate affair wrecked my plans, and it was not until this spring of 1940, in the lull which preceded the German offensive, that I was able to carry them out. Wansa’s visit to Baghdad was opportune, for she most kindly gave me a letter to friends in Baashika, as well as satisfying my curiosity about many things I wished to know.

Here I must apologize for this book. It is not a serious contribution to the literature about the sect, although when I went the ostensible reason of my visit was to see how the Yazidi spring festival fitted into the pattern of the other spring festivals of an ancient and conservative land. Being there, however, female inquisitiveness led me into byways, so that those who really do mean to study this interesting people scientifically and thoroughly, may find here scraps and tags of information which may be useful to them. I hope sincerely that some honest and skilled investigator may undertake the task, for I am convinced that most of what has been written hitherto about the Yazidis is surface scratching, often incorrect, based upon hearsay instead of upon prolonged direct investigation. Without a good knowledge of the Kurdish language it would be impossible to gain the confidence of the religious chiefs or to understand chants sung by the qawwals.

In a book I wrote eighteen years ago, I repeated many tales about the Yazidis current amongst their neighbours, and others have taken their material from similar sources, and sometimes borrowed from my chapter. At all these legends, reports and current tales I look now with the utmost caution and suspicion. Years spent in studying another minority and another secret religion have taught me how unreliable hearsay evidence is, and in this book, therefore, I repeat only what I gather from Arabic-speaking Yazidis themselves, or that which I myself witnessed.

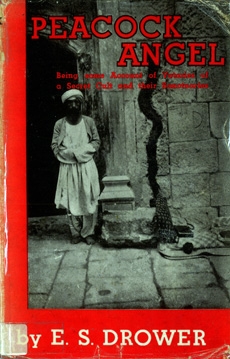

The Yazidis are spoken of as Devil-Worshippers. Apart from the fact that Shaikh ‘Adi bin Musafir, their principal saint, was recognized in his time as an orthodox Moslem, my personal impressions are contradictory of this. I cannot believe that they worship the Devil or even propitiate the Spirit of Evil. Although the fchief of the Seven Angels, who according to their nebulous doctrines are charged with the rule of the universe, is one whom they name Taw‘us Melkd, the Peacock Angel, he is a Spirit of Light rather than a Spirit of Darkness.

“They say of us wrongly,” said a qawwal to me one evening, “that we worship one who is evil.”

Indeed, it is possibly the Yazidis themselves, by tabooing all mention of the name Shaitan, or Satan, as a libel upon this angel, who have fostered the idea that the Peacock Angel is identical with the dark fallen angel whom men call the Tempter. In one of the holy books of the Mandaeans the Peacock Angel, called by them Malka Tausa, is portrayed as a spirit concerned with the destinies of this world, a prince of the world of light who, because of a divinely appointed destiny, plunged into the darkness of matter. I talked of this with the head of the qawwals in Baashika who, honest man, was not very clear himself about the point, for one of the charms of the Yazidis is that they are never positive about theology. It seemed probable to me, after this talk, that the Peacock Angel is, in a manner, a symbol of Man himself, a divine principle of light experiencing an avatar of darkness, which is matter and the material world.

The evil comes from man himself, or rather from his errors, stumblings and obstinate turnings down blind alleys upon the steep path of being. In repeated incarnations he sheds his earthliness, his evil, or else, if hopelessly linked to the material, he perishes like the dross and illusion that he is.

I say that this seems to me a probable conception, but I have no scrap of evidence that it is the Yazidi theory, no documentary proof, no dictum from the Baba Shaikh, who is the living religious head of the nation. One Yazidi propounded to me the curious theory that the accumulated experiences of various earthly lives was, on the Day of Resurrection, gathered into one over-soul, but that the individuals who had once lived those lives continued as separate entities, but how this was possible he did not explain.

However, as I have already intimated, I am not concerned here with Yazidi creeds, but with themselves and the shape of their daily life as I saw it. Whatever may be the vague beliefs of their religious chiefs, their practised religion is a mystical pantheism. The name of God, Khuda, is ever on their bps. God for them is omnipresent, but especially reverenced in the sun, the ' planets, the pure mountain spring, the green and living tree, and even in cavern and sacred Bethel stone some of the mystery and miracle of the divine he hidden.

As for propitiation of evil, I can say sincerely that I found less amongst them than their neighbours. Moslems and Christians wear three amulets to the Yazidi one, and though a Yazidi is not averse to wearing a charm against the Evil Eye, many so-called devilworshipping children go without, though few Moslem or Christian mothers would dare to take their babies abroad without sewing their clothes over with blue buttons, cowries, and scraps of Holy writ, either Qur‘an or Bible.

A third impression was of their cleanliness. In the village of Baashika there was no litter, no filth, no mess of discarded cans or scattered bottles. To be honest, I saw a few rusty tins, but these had been carefully collected, filled with water, and taken to a shrine, there to be left as offerings. Petroleum-tins are utilized to store precious home-pressed olive-oil, so that pitchers and jars are still employed for water-carrying. Paper is rarely used. What one buys in the bazaar is taken home in a kerchief or in a corner of the robe. There is no faint and' revolting stench of human filth such as there is in most Arab villages in central and southern ‘Iraq, or on the outskirts of the larger towns, where any ditch or wall serves for a latrine. As a newspaper is a rarity, one sees no untidy mess of soiled paper. What they do with their dead animals I do not know, but I neither saw, nor smelt, a decaying corpse, whereas even in such a modern town as Baghdad, owing to the laziness of municipal cleaners who dump dead animals behind the city to save themselves the trouble of the incinerator, any walk outside the city area may mean breathing polluted air. I complimented the mayor of the village, and he replied simply, “They are clean people.” 1 Nevertheless, to the authorities belongs the credit of tapping the pure spring water as it issues from the mountain at Ras al-‘Ain and bringing it by pipe to the centre of the village so that women can fill their water-pots with good water.

At Shaikh ‘Adi I realized what a danger people like myself can be to such a place when I saw the result of my giving a page of pictures from an illustrated paper to the children of the guardian of the shrines. Quickly tiring of looking at the images, they tore it up and the untidy fragments were borne by the wind about the flower-grown courts of the sanctuary.

To return to this book. It would be tedious to recount all the conversations which led to such information as is set down here about marriage and birth and such events. I have therefore woven them, I fear in a somewhat haphazard way, into the narrative of the whole. The book is, therefore, merely a personal impression of day-by-day happenings and friendships.

To me this stay of a spring month with the Yazidis was a very lovely experience, and if I fail in transmitting its flavour and quality, it is that I am incompetent.

To have escaped in the midst of a European war into places of absolute peace and beauty is an experience which one would gladly share with others.

An old friend of mine in this city of Baghdad, echoing unconsciously an ancient belief, once told me that if ear and spirit can be cleared of the din of this world, one can hear at rare and high moments the separate notes that the worlds give forth, the sun, the earth, the moon and the stars, as they move and vibrate according to the law of their being. The whole blends, he said, into perfect harmony, into an exquisite chant of joy. Whatever this music may be, and whatever its purpose or purposelessness, I fancied that, for a moment or two, during these weeks of escape, I caught a fleeting bar, a faint echo of lovely and eternal harmonies, far removed from the clash and fret of men.

Chapter I

Baashika

“Not of wars, not of tears, but of Pan would he chant, and of the neatherds he sweetly sang”

Theocritus.

I WAS to stay with friends in Mosul, and it was my host, Captain C., who had taken infinite trouble in arranging for me, with the permission of the authorities, lodging in the Yazidi village that I had chosen as my headquarters. The road thither is impassable in wet weather, and I felt apprehensive when Captain C. showed me pock-marks more than an inch deep in his flower-beds, and plants battered to the ground by hail which had fallen the day before. I was still more anxious when the sky darkened as if Sindbad’s roc were approaching. Sure enough, rain followed, heavy and sharp, but the C.s comforted me. A sun next morning and a good wind would dry the road at this time of the year, they assured me.

And so it was. I woke to a blue, rain-washed day.

Whilst I paid calls upon the Governor and Mayor, the roads were drying in the bright sun and fresh wind, so that all was well for our start. A kindly thought had led the local officials to allot me a Yazidi policeman as guardian and guide, an honest-looking lad who spoke Kurdish as well as Arabic, and therefore could act as interpreter when the latter language failed. As a guardian he was unnecessary, but he proved to be a pleasant companion. He and his baggage were stowed into our taxi and off we went.

The road to Baashika is only so-called by tradition...

|