The folk literature of the Kurdistan Jews: an anthology

Yona Sabar

Yale University

The Aramaic-speaking Kurdistani Jews are members of an ancient Jewish community which, until its emigration to Israel, was one of the most isolated in the world. Throughout their long and turbulent history, these Jews maintained in oral form a wealth of Jewish literary traditions embellished with local folk-lore. This volume is the first translation and anthology of their richly imaginative literature.

Yona Sabar, himself a Kurdistani Jew, offers representative selections from the types of Kurdistani literature: epic re-creations of biblical stories, midrashic legends, folktales about local rabbis, moralistic anecdotes, folk songs, nursery rhymes, sayings, and proverbs. Sabar's introduction and notes are a storehouse of information on the history and spiritual life of the Kurdistani Jews and on their relationship to the Land of Israel.

Because almost all the Kurdistani Jews now live in Israel and speak Hebrew, there is very little new literary activity in their Neo-Aramaic dialects. This delightful anthology captures the essence of Kurdistani Jewish literature, presenting it for public enjoyment and preserving it for the future.

Yona Sabar is associate professor of Hebrew at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Content

List of illustrations preface / ix

Preface / xi

Introduction / xiii

I. Kurdistan and the Kurds / xiii

II. The Jews of Kurdistan: Origin and History / xv

III. Occupations and Economic Conditions / xxi

IV. Religious and Spiritual Life / xxv

V. Relationship to the Land of Israel / xxix

VI. The Literature of the Kurdistani Jews / xxxii

Note on the English Translation / xli

Chapter I Adam and Eve / 3

Chapter II Joseph and Zulikhaye / II

Chapter III Joseph and His Brothers in Egypt / 16

Chapter IV Moses and Bithiah, the Daughter of Pharaoh / 24

Chapter V The Death of Moses / 33

Chapter VI The Duel of David and Goliath / 42

Chapter VII King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba / 55

Chapter VIII Solomon and the Cushites / 62

Chapter IX The Prophet Elijah / 68

Chapter X Lel Huza: Women's Lamentations for the NinBarzānīb / 71

Chapter XI The Conversion of Onkelos to Judaism / 84

Chapter XII The Mission of Bar Kappara to Annul a Decree against the Jews / 89

Chapter XIII David Alroy, the Messiah from Kurdistan / 94

Chapter XIV Apology of a Preacher / 101

Chapter XV Legends about Rabbi Barazān ben Nathanael hal-Levi Bazani Adoni and Other Rabbis of Kurdistan / 104

Introduction

1. How Rabbi Samuel, a Hopeless Child, Became a Poet and a Scholar

2. How Rabbi Samuel, an Illiterate Weaver, Became the Rabbi of Mosul

3. How Rabbi Samuel Wrought a Miracle

4. The Flight of Rabbi Samuel from ã to Amidya and His Death There

5. The Power of Rabbi Asenath, the Daughter of Rabbi Samuel

6. The Death of Rabbi Simeon Doga, the Astrologer

7. The Conversion of the Emir of Nerwa to Judaism by Rabbi Mordecai

Chapter XVI Selections from the Chronicle of Jonah ben Gabriel / 130

Chapter XVII Folktales / 135

1. The Angel of Death and the Rabbi's Son

2. The Jewish Cobbler and the Kurdish Robber

3. By Virtue of a Single Good Deed

4. The Old Man's Treasure

5. The Poor Man's Trust in God

6. The Unfortunate Shoemaker

7. The Happy Carpenter

8. The Luck of a Child

9. One Gram More, One Gram Less

10. Hamdullah, Nisan, and lyyar

11. The Power of Man

12. The Ewe, the Goat, and the Lion

13. The Fox as Tailor and Weaver

14. The Raven, the Fox, and the Rabbit

15. The Serpent and the Poor Man

16. The Pain from a Blow Heals, the Pain from a Word Does Not

17. The Child Whose Shirt Stuck to His Skin

18. The Righteous Man, the Black Man, and Our Master Moses

19. The Donkey Who Gave Advice, the Ox Who Became Sick, and the Rooster Who Was Clever

20. The Prince Who Became a Pauper

21. The Letter to God

22. The Carpenter, the Tailor, and the Rabbi

23. The Sword of Redemption

24. The Amulet

25. The Midwife, the Cat, and the Demons

Chapter XVIII Nursery Rhymes / 193

Chapter XIX Folk Songs / 197

Chapter XX Proverbs and Sayings / 202

List of abbreviations / 224

Glossary / 225

Selected bibliography / 229

Index / 233

General Index / 233

Scriptural References / 244

Rabbinic References / 246

Tale Types, Motifs, and IFA Numbers / 247

PREFACE

The Jews of Kurdistan are unique in more than one way. They are considered one of the most ancient Jewish communities, tradition-ally tracing their origin to the first Israelite exiles taken away by the Assyrian kings. Until their emigration to Israel they were one of the most isolated Jewish communities in the world. Scattered in about two hundred villages in the rugged and almost inaccessible mountains of Kurdistan, they had very little contact with the rest of world Jewry. Yet in spite of their isolation and other adverse factors - such as general abject poverty, small and scattered communities, constant wars among the local Kurdish chieftains - this community maintained orally a unique wealth of ancient Jewish literary traditions embellished with themes from local Kurdistani folklore and daily life.

I have made an effort to include in this volume representative selections from the various genres of this literary heritage: epic re-creations of Biblical stories, Midrashic legends, folktales about local rabbis, Jewish and general Near Eastern moralistic anecdotes, folk songs, nursery rhymes, sayings, and proverbs.

I owe many thanks to Professors Judah Goldin and Franz Rosenthal, and to Dr. Leon Nemoy, for their encouragement in the various stages of this work. I am especially grateful to Dr. Nemoy for his painstaking editorial correction of my style and for his wise advice as to the type of selections to be included in the anthology. I am also grateful to Charles Grench and Sharon Slodki, at the Yale University Press, for their kind efforts and thoughts in making this volume as attractive in form as in content.

Among others who have assisted me are Professors Dov Noy and Aliza Shenhar of the Israel Folktale Archives, who very kindly made available to me the Archives' large collection of folktales of Kurdistani Jews. I am also much indebted to Dr. Stephen Stern, who prepared the motif index, and to the editors and publishers who gave me permission to include selections from their publications.

My wife, Stephanie, read the first English draft of each selection and assisted me in other aspects of this work, in addition to providing generous moral support.

Introduction

1. Kurdistan And The Kurds

I. The word Kurdistān in Persian means "the land of the Kurds." It seems to have been coined by the Seljuks, the Turkish dynasty that ruled the Near East between 1038 and 1194 C.E.,¹ but terms designating the Kurds or their land appear already in ancient times, going back as far as 2000 B.C.E. The Kurds are mentioned in Sumerian and Assyrian records, as well as in classical Greek and Latin works, particularly Xenophon's Anabasis (401-400 B.C.E.).² In Aramaic the region was known as betkardu, ³ and in the Aramaic translation of Onkelos (fourth century C.E.) the Biblical hare 'Ararat (Gen. 8:4), "the mountains of Ararat," where Noah's ark had rested, is identified as ture kardu, "the mountains of Kurdistan. "4 There are a few references to kardu and arduyyim in the Talmud (sixth century C. E.) as well.5

…..

1.Minorsky, pp.1130, 1140.

2.Ibid., p. 1132. Xenophon calls the area the country of the Carduchi"; see his Anabasis, bits. III—IV (pp. 97-170), which deal with the march of the Greek soldiers through Kurdistan and their fierce fights with the Kurds in the mountains. It is interesting that already Xenophon was impressed by the rugged nature of Kurdistan and the warlike character of the Kurds: "These people [the Carduchi), they said, lived in the mountains and were very warlike and not subject to the [Persian) king. Indeed, a royal army of one hundred and twenty thousand had once invaded their country, and not a man of them had got back, because of the terrible conditions of the ground they had to go through" (p. 127).

3.The spelling with A. suggests a Semitic etymology, "to be strong" (Akkadian); for this and other possible derivations (e.g., Persian gurd, "hero") see Minorsky, pp. 1133-34.

4.For other ancient sources of this tradition see Ginzberg, 5, 186; 4, 269: "On his return to Assyria, Sennacherib found a plank, which he worshipped as an idol, because it was part of the ark which had saved Noah from the deluge. He vowed that he would sacrifice his sons to this idol if he prospered in his next ventures. But his sons heard his vows, and they killed their father, and fled to Kardu, where they released the Jewish captives confined there in great numbers"; 6, 479: "Haman's son Parshandatha, who was governor of Kardunya, where the ark 'rested.'" A local tradition referring to the presence of the remnants of Noah's ark and altar on a local mountain ("Jabal Judi") is mentioned by various travelers; cf., e.g., Benjamin II, p. 94: "At the base of the mountain stand four stone pillars, which, according to the people residing here, formerly belonged to an ancient altar. This altar is believed to be that which Noah built on coming out of the ark [Gen. 8:20). They likewise assert that his remains are buried in the vicinity; they do not, however, specify the exact spot. I myself obtained several fragments of the ark which appeared to be covered with a kind of substance resembling tar."

5.Cf. B. BB 91a: "Our forefather Abraham was imprisoned for ten years, three in Kutha and seven in Kardu'; B. Yeb 160: "Proselytes may be accepted from among the Karduyyim." See also n. 4, above.

Yona Sabar

The folk literature of the Kurdistan Jews: an anthology

Yale University

Yale University Press

The folk literature of the Kurdistan Jews: an anthology

Translated with introduction and notes by Yona Sabar

Volume XXIII

Yale Judaica Series

Editor

Leon Nemoy

Associate Editors

Judah Goldin

Saul Lieberman

Yona Sabar

Associate Professor of Hebrew

University of California, Los Angeles

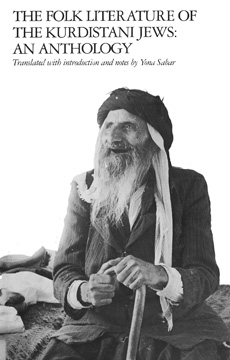

Jacket photo: Yona Gabbay, a well-known storyteller from Zakho.

Photograph by Stephanie Sabar (Jerusalem, 1967).

Yale University press

New Haven and London

ISBN: 0-300-02698-6

This is one of a series of volumes that will be published with the support of the Judaica Series Fund established by the William P. Goldman and Brothers Foundation, Inc. The preparation of this volume was aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The findings, conclusions, etc. do not necessarily represent the view of the Endowment. Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College. Copyright © 1982 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Illustrations

Frontispiece Map of the major Jewish communities of Kurdistan. following page 100 Yona Gabbay, a well-known storyteller from Zakho. As a merchant who traveled throughout Kurdistan, he heard and told many folktales. He died in Jerusalem in 1972, when he was more than one hundred years old. Photograph by Stephanie Sabar (Jerusalem, 1967). The author reading a Neo-Aramaic manuscript with hakam 'Alwān Avidani. Photograph by Stephanie Sabar (Jerusalem, 1969). Sandor, a Jewish village in Iraqi Kurdistan, ca. 1934. Courtesy Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Girl wearing case amulet with pendants. Courtesy Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Sandor village schoolchildren, ca. 1934. Courtesy Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Man watching teapot. Courtesy Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Woman at a nomadic-style loom. Courtesy Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Page from a Neo-Aramaic manuscript; the last page of a Midrash on Běšallah (Exodus), with a colophon, copied in Nerwa in 1669 C. E. Courtesy Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem.

PDF

Downloading this document is not permitted.

|