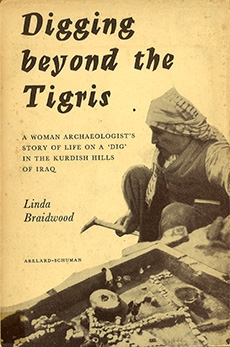

Digging beyond the Tigris

Linda Braidwood

Abelard-Schuman

Linda Braidwood tells the story of an archaeological expedition from its original planning stage in the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute to the actual field work in the Kurdish hills of Iraq, 200 miles north of Baghdad.

Mrs Braidwood, archaeologist wife of the expedition’s director and mother of two children, who accompanied them, tells us how an expedition is planned and financed; how the staff is chosen, and supplies and equipment assembled, how the workmen who do the actual labour are hired and how the daily routine of living and working on the ‘dig’ is organized.

The object of the expedition was to seek evidence of the great change in man’s history from cave-dwelling savagery to the establishment of settled villages of farmers and herdsmen.

Mrs Braidwood, however, is as interested in the present as in the past, and her story of life in modern Kurdish villages is as readable as her account of the ‘dig’.

Linda Braidwood was educated at Wellesley and the Universities of Munich, Michigan, and Chicago. She is married to the archaeologist Robert J. Braidwood.

She herself is a staff member of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. In 1937-38,1947-48, and 1950-51 she was a member of its expeditions to Syria and Iraq. Between digging seasons she works on the Institute’s publications, and she is also an editorial advisor for Archaeology.

Contents

Introduction / ix

1. How we came to dig Jarmo / 3

2. Getting ready to go / 9

3. From Beirut to Damascus / 23

4. Baghdad / 30

5. Up to Jarmo / 42

6. Getting settled—Jarmo style / 57

7. We begin to dig / 69

8. An interlude of dancing / 81

9. Getting into harness / 85

10. To market, to market / 100

11. A Kurdish market place no / 110

12. Up from hard-boiled egg pie? / 120

13. Luncheon for the governor / 134

14. Not so light housekeeping / 139

15. Ailments: automotive and human / 155

16. Junior camp members / 170

17. Animal problems / 182

18. The gathering of the staff / 193

19. Gran’ma becomes an archeologist / 203

20. Spring digging / 210

21. Holidays / 229

22. A (pleasant) state of siege / 244

23. A Kurdish wedding and a cherry spree / 251

24. A busman’s holiday / 261

25. Digging ended / 269

26. The division / 282

27. Farewell to Jarmo / 286

INTRODUCTION

This is the story of a happy archeological digging season in the Near East—of how it was planned and how the expedition lived and worked in the field.

In the old days the archeologist was a romantic individual in a sun helmet. He brought his museum or his patron the loot of royal tombs or of the great cities of known fame—Babylon, Ur, and Nineveh.

The modern archeologist is not interested in glittering antiquities as such. He is searching for general understanding of man’s past rather than for royal tombs. He is contributing ideas rather than loot.

Jarmo, the site we excavated, promised to lead to a clearer understanding of the first great change in human history; the time when men first settled down in villages and lived by farming and herding. If we could learn a little more about this, our year would be well-spent.

The Oriental Institute for which we work knew, when our proposed expedition was made part of its budget, that Jarmo would yield no spectacular objects. Although of late years the effective income of the Institute has dwindled, as a research organization it still feels morally obligated to concentrate on those points in the record about which little or nothing is known, whether the finds are spectacular or not. This unique Institute was founded at the University of Chicago by the late great James Henry Breasted in 1919. Professor Breasted was an Egyptologist by training, a decipheror of hieroglyphic inscriptions, but this hardly suggests his tremendous breadth of vision.

Breasted sought to “recover the lost story of the rise of man.” He asked “how did man become what he is?” He knew that, to understand an ancient and extinct culture, the archeologist could not do the job alone. He visualized a really complete expedition as ideally including such trained men as botanists, paleontologists, geologists, climatologists, and anthropologists—who would all work as a team with the archeologist in recovering the story of an ancient culture as it fitted into its natural surroundings.

Breasted focussed his own and his Institute’s interests in the ancient Near East “for there still lies the evidence out of which we may recover the story of the origins and the early advance of civilization, out of which European culture and ' eventually our own came forth.” He used his tremendous enthusiasm to fire the imagination of men like Rockefeller and others, and gained their support for his work. Before his death in 1935, Dr. Breasted was able to see some of his plans materializing. Oriental Institute field expeditions were at work in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Palestine, and Egypt; of the sites under excavation, those of Megiddo and Persepolis are probably most familiar by name to the general public.

The archeologist of today works under different circumstances than his romantic predecessors. Aware of his respom sibilities as a citizen in a troubled world, he tries to do hit share towards contributing to good-will between his own country and the country in which he is working. He is unhappy about Hollywood-struck, gun-toting, boy-explorer types of “expeditions” which accomplish little scientifically and do great damage to their country’s prestige.

To make his dig tick, the modern archeologist also has to count on a tremendous amount of cooperation and good-will —from his university and various foundations, from his friends and colleagues, from the merchants and shipping agencies who supply and transport his strange needs, from the officials and country folk of the land where he works, and especially from his own field staff.

In our case we are indebted to hundreds of people for their good-will and cooperation. The director of the Oriental Institute, its administration staff, and the University of Chicago’s purchasing agents did more than their share. Many Chicago friends helped us. Our doctors and dentist friends somehow arranged their schedules so that a host of preventative shots, last minute dental care and good advice were all provided. Our families had to rally around to take care of our affairs while we were out of the country.

We are above all much indebted to the Institute’s present director, Dr. Carl H. Kracling, who believed in our aspirations for Jarmo and its potential yield in knowledge. He not only encouraged us but actively aided us in every possible way, budgetary, administrative, or otherwise.

Out in the field, the director and the staff of the Iraq Government’s Directorate General of Antiquities, our friends in Kirkuk, and various local officials and village headmen did everything they could for us. Our Arabic and Kurdish workmen cooperated with each other and with us—making for good efficient digging.

And finally the staff—there were a good many of us, our quarters were cramped and we worked a long season together. In spite of this, everyone was unusually congenial and cooperative in every way. One couldn’t have dreamed up a happier staff.

At home again, we are still dependent on the cooperation of the staff and many non-archeological experts who will help us in studying the excavation materials.

We want to thank our friends and acquaintances—from the States to Baghdad, to the Kurdish foot-hills and back to the States again—for all their help.

Digging Beyond the Tigris

[1] how we came to dig Jarmo

“we’ll try to get it for you, bob,” said the director, resignedly shaking his head. “I can see you need that amount. But you know how the University finances are these days.”

Bob had just handed in the digging budget of our proposed season at Jarmo. We had cut every corner we could. The budget was lean, but efficient. Now all we could do was to keep our fingers crossed. Our Jarmo estimate was only one of the items in the Oriental Institute’s budget. If the University Central Administration had to cut the entire Oriental Institute budget too much, there wouldn’t be any question of a dig the coming season.

It was well along in September, 1949, when Bob suggested one night that we should tackle the budget for the next digging season. We got out our old accounting sheets and started to work.

“We know we’re going to dig Jarmo, so how about calling it the Iraq-Jarmo Project?” said Bob. “A fine idea,” I …

Linda Braidwood

Digging beyond the Tigris

Abelard-Schuman

Abelard-Schuman

Digging beyond the Tigris

A Woman Archaeologist’s

Story of Life on a ‘Dig’ in the

Kurdish Hills of Iraq

By Linda Braidwood

Abelard - Schuman

London and New York

© Copyright Abelard - Schuman Ltd., 1959

Printed in the U.S.A, and bound in Great Britain for

Abelard - Schuman Ltd., 38 Russell Square, London, W.C.I

and 404 Fourth Avenue, New York 16, N.Y.

Abelard-Schuman Ltd. Publishers

London and New York