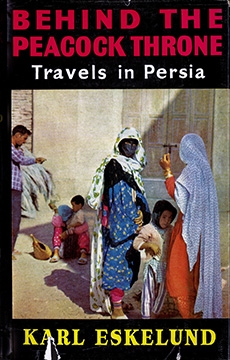

Behind the Peacock Throne: Travels in Persia

Karl Eskelund

Alvin Redman

This well-known Danish travel writer has added another volume to his very successful world travel series. This time it is the result of a three months’ stay in Persia with his Chinese wife. Karl Eskelund writes informatively about the peasants and the land reforms and in a letter describing the book he says:

“All this may sound very serious, but I have not really treated it as economical problems, only described it from the point of view of the ordinary farmer. Among many other things the book tells about the strange religious sect (a kind of devil-worshippers) which we discovered in a small town where we spent a couple of weeks, the kurdish nomads, sturgeon fishing in the Caspian, the Turkomans who have become farmers, the sacred city of Mashhad, where I was nearly mobbed when trying to photograph the golden shrine (and where I tried opium). There is also something about the children who weave the famous Persian rugs, Persepolis, the ancient religion of fire-worshipping (there are still a few temples), the Bahai religion (which comes from Persia), and a trip through the south where the starving nomads sometimes become highwaymen. This journey ends in Bandar Abbas, the ‘Siberia’ of Persia, where the women wear black masks. The final chapter is an interview with the Shah”.

Contents

Chapter

1 A Toman is a Toman / 11

2 The Worshippers of Shaitan / 20

3 Words That Beguile Thee / 32

4 The Black Eggs / 43

5 Tell It to the Shah / 52

6 The Sacred City / 62

7 Baha’i / 75

8 Only on Fridays / 86

9 The Old Children / 91

10 Persepolis / 101

11 The Eternal Flame / 109

12 The Thirsty Land / 118

13 The Road to Bandarabbas / 126

14 The Black Masks / 136

15 The Peacock Throne / 142

Index / 153

CHAPTER ONE

A Toman is à Toman

Dawn Was Just beginning to break when we left Erzerun, the last Turkish town before the Persian border. For hours the bus drew a trail of dust across the bare plains and over the mountains. Kurds stared at us from the flat roofs of their clay huts, the women’s silver ornaments sparkling in the sun. The men wore loose shirts tied at the waist with coloured sashes.

At noon we reached a wide, deserted valley. On our left, way up north where the Soviet border begins, a snowcovered peak was outlined against the blue sky. It was Ararat, the sacred mountain where Noah landed his ark after the deluge.

Finally, some barracks appeared in the barren waste far ahead. “Now we’ll soon be there,” declared Rashid, a Persian rug dealer who knew a smattering of English. He had crossed the border many times before and so, as a matter of course, had assumed leadership of our motley little group. Apart from Rashid, my Chinese wife and myself, it consisted of a young English couple and four Persian students’ holiday-bound from their studies in Germany.

The English couple, who were on their way to Australia, had originally planned to hitch-hike, but had been forced to give it up. Motorists in this part of the world could see no reason why people from the prosperous West should travel free of charge.

At last the bus drew to a stop in front of a long building shared by the Turkish and Persian border authorities. You entered one end with your luggage and—with a bit of luck—emerged at the other some hours later. According to Rashid, this was one of the toughest borders to cross in the whole Middle East, which is saying quite a bit.

As he had predicted, the Turkish half was child’s play. It took some time, though, for the officials spoke no word of any foreign language, but they did not try any funny business on us. The Turks, who until a few centuries ago were nomads in Central Asia, are “too primitive to be smart,” as Rashid remarked with a note of condescension in his voice.

Getting through ahead of the others, I sat down in a hall in the middle of the building, a kind of no-man’s-land with a Turkish sentry at one door, a Persian at the other. Before long an attractive young couple entered, a Dutch woman with her Persian husband. They had visited his parents in Teheran and were now on their way back to London where he studied medicine. When he suggested that we could save the money-exchanger’s fee if I gave him my Turkish lira for his Persian tomans (one toman is slightly less than a shilling), I readily agreed.

I still blush at the thought of what happened next. I had said good-bye to the couple and was, from an old habit, recounting the money, when a middle-aged man in smart European clothes entered from the Persian side. He greeted …

Karl Eskelund

Behind the Peacock Throne

Travels in Persia

Alvin Redman

Alvin Redman Limited

Behind the Peacock Throne

Travels in Persia

Karl Eskelund

Alvin Redman

London

Copyright © Karl Eskelund 1965

Published by

Alvin Redman Limited

17, Fleet Street,

London E.C4

1965

Printed in Great Britain By

Bristol Typesetting Co. Ltd.

Barton Manor - St. Philips

Bristol 2