|

FOREWORD

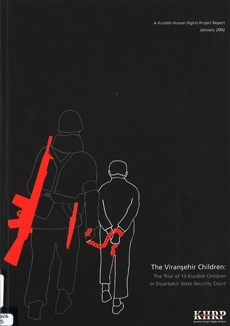

This report is about the arrest, detention and prosecution of a group of children in the Kurdish town of Viranşehir in Southeast Turkey, following a street demonstration in January 2001. The demonstration was to protest against prison conditions in the context of Turkey’s continuing “F-Type” prison crisis.1 Twenty-eight children were initially detained, some for over a month, and 13 eventually charged with supporting an illegal organisation, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Two of those charged were only 12 years old, the others were aged between 14 and 17. Their trial proceeded in the State Security Court in Diyarbakir, and a delegation from KHRP observed one of the hearings. At the time of writing, the case is still ongoing.

This report outlines the applicable international human rights standards and highlights the many ways in which Turkey has contravened the rights of the Viranşehir children. What emerges is that Turkey has fallen short both of human rights safeguards guaranteed to all, and of the particular protections pertaining to children contained in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international instruments that bind Turkey. Among the protections that the Viranşehir children should have been, but were not, afforded are: separate detention of adults from children; the duty to deal with the cases speedily; privacy and the need to consider the “best interests” of the children; and being dealt with by separate systems of juvenile justice.

KHRP is particularly concerned about the possible psychological problems caused when children are detained in the circumstances described in this report. In addition to being questioned without the presence of lawyers and signing confessions in a language some of them did not understand, they also allege ill-treatment and threats of ill-treatment, and six of them were kept in custody for more than a month before being released on bail.

We also remain concerned that children as young as 11 can be, and are, prosecuted for exercising their right to freedom of speech and association, under laws that criminalise forms of non-violent protest, and in State Security Courts that fail to provide basic safeguards for adults as well as children.2

Our other concerns relating to this particular case are listed at the end of the report, together with our recommendations addressed to the Government of Turkey.

The wider context in which the case of the Viranşehir children took place should be not be forgotten. The situation of Kurdish children in Turkey is extremely difficult. Up to three million Kurds have been internally displaced as a result of the conflict in the Southeast since 1984.

Many Kurdish families live in shantytowns on the margins of the cities and face unemployment and dire poverty while still coping with the traumas of war and conflict. The Kurdish children of Turkey’s Southeast - bom into the destitution and violence of the State of Emergency areas - continue to suffer in an environment of serious human rights abuses at the hands of the State.

These abuses include the deaths and ‘disappearances’ of family members and friends; the destruction of family homes and ways of life; the repression of free expression including the right to speak in their mother tongue; and - in the all too many instances - torture and ill-treatment.

The delegates also saw very young children on the streets selling tissues, lighters and the like. Although schooling in Turkey is free, the KHRP delegation was told that classes are severely overcrowded, and that many children of displaced families do not attend school because parents could not afford to buy the books and equipment needed.

The Government of Turkey has been criticised by the Committee on the Rights of the Child regarding, amongst other matters, their inadequate system of birth registration. It is partly as a result of this unsatisfactory registration system that KHRP is unable to give an indication as to the percentage of the population of Turkey that is ethnically Kurdish. Officially, the population of Turkey is some 65.5 million, with Kurds comprising between 15 and 20 million and having a higher average birth rate than the national average. Kurdish children therefore constitute as much as 25 percent of all children in Turkey. And yet, as indicated in this report, the word Kurdish does not even appear in Turkey’s state report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child. Further, there is not one juvenile court situated in the area of eastern Turkey in which Kurdish children live.

KHRP would like to extend its warm thanks to Angela Gaff and Mary Hughes for observing the trial on KHRP’s behalf, and to Angela Gaff for preparing this report.

Kerim Yildiz

Executive

January 2002

1 Regarding this crisis, see The F-Type Prison Crisis and the Repression of Human Rights Defenders in Turkey, KHRP, OMCT and the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network, October 2001. Protestors against the “F-Type” prisons - which are characterised by 1- and 3-person cells - are primarily concerned with the increased risk of isolation and torture in custody threatened by these newly deployed prisons.

2 See Annex 6 - Statistics of children tried and sentenced in the Diyarbakir State Security Court.

Introduction

On 3 April 2001, two British lawyers, barrister Mary Hughes and solicitor Angela Gaff, both of whom specialise in the representation of children, travelled on behalf of the Kurdish Human Rights Project to Diyarbakir in Southeast Turkey, to observe the trial of 13 children who had been arrested, along with 15 others, on 8 January 2001. The children had been accused of supporting an illegal organisation, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and of facilitating their activities by having participated in an unauthorised demonstration in protest against changes in Turkey’s prison system, and shouting pro-PKK slogans. Mandatory terms of imprisonment of three to five years were applicable. The arrest of the children attracted a great deal of media attention. The first hearings in the case were held on 17 January and 5 February 2001.

The hearing that was observed by the delegation took place on 5 April at the State Security Court in Diyarbakir and was adjourned to 6 June, in order that reports regarding the understanding of those children between the ages of 11 and 15 of the nature of the offences could be determined. Since the return of the delegation, further hearings have taken place on 13 September and 27 December 2001, and a further hearing has been set for 7 March 2002 at which the Prosecutor is expected to recommend whether or not the case should proceed. The delay in this case being finally dealt with is in itself inconsistent with international children’s rights law, which emphasises that juvenile penal proceedings should be dealt with most expeditiously, taking into account children’s sense of time. Article 40(2)(b)(iii) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 provides that a child accused of breaching the penal law should have the matter determined “without delay”.3

In addition to attending the hearing, the delegates were also able to meet with the Chief Public Prosecutor. However, the delegation was advised that a request to observe the hearing had been made by the Diyarbakir Teaching Union, and that permission had been refused. It should be noted that the children themselves did not appear at the hearing; indeed they were not required to do so. The delegates were in fact not able to meet the children during their stay in Turkey. Many of the children came from families of seasonal workers, who move around routinely in search of work.

In addition to their attendance at the hearing, the delegates met with the lawyer for the Viranşehir children and other members of the Human Rights Association of Turkey (IHD), Diyarbakir branch. The delegates also met with representatives of a number of other local groups who were able to supply further information concerning the case or the context in which it occurred. These included the Teachers’ Union, Goc-Der (an NGO working with the internally displaced), the Turkish Foundation for Human Rights, the Diyarbakir Bar Association and the Women’s Platform.

This report was written by Angela Gaff. Its purpose is to discuss human rights issues arising out of the case in question and general principles of the Turkish juvenile justice system as applied to Kurdish children and in particular the practice of trying children in the State Security Courts.

The delegates wish to express their thanks to all those who cooperated with them in their mission.

…..

3 Article 10(2)(b) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Turkey has not yet ratified, provides that juveniles should be brought “as speedily as possible” to adjudication. Furthermore, Rule 20 of the Beijing Rules provides that each case from the outset should be handled “expeditiously without any unnecessary delay.” |