|

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

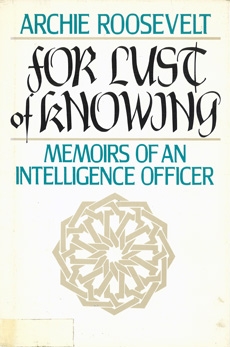

THIS IS NOT the story of my life, but of my experiences as an intelligence officer in the Islamic world and its fringes. It does tell of my beginnings and how I got pointed in that direction, but once launched on this course, I confine the narrative mostly to what I witnessed myself in that part of the world. Also, requirements of space necessitated my sticking to a single story line, and I hope my relatives, friends, and colleagues won’t be disappointed when I fail to name them as I plunge headlong on my way.

I have so many persons to thank for helping me in my career that I could not possibly mention them all. First there were my parents. Then my teachers, at home, at school, and in college. Truman Smith, Edwin Wright, and Paul Converse were among the many army officers who guided my youthful steps. And ambassadors, particularly Loy Henderson, George Allen, George Wadsworth, John Davis Lodge, and David Bruce, all, alas, no longer able to read these pages, and one, George McGhee, who I hope will do so. At least two of my three favorite directors of the Central Intelligence Agency can still read my words of appreciation. To my colleagues in the Agency and the Foreign Service with whom I passed those adventurous years, apologies for naming so few of you. You deserve better of me.

I also wish to pay tribute to friends and colleagues in the dozen or so years I’ve passed at the Chase Manhattan Bank. Some of my favorite trips to the countries described in this book were made with our successive chairmen, David Rockefeller and Bill Butcher, in the “company plane.”

I must make special mention of the wonderful secretaries, too many to name but all remembered, who have helped me throughout my career — and who sometimes saved me from disaster. More than once, having written a cable full of wrath before lunch, I hurried back afterward to try to alter it, only to find a wise secretary had delayed it for me to consider from a calmer perspective. The Agency secretaries, like its officers, are an elite corps. I also had a first-rate secretary at the Chase Manhattan Bank, Liz Callaghan, who, alas, died before she could read this tribute.

This book is based almost entirely on my own recollections, so there are no sources to cite, and only a couple of times did I call on others to help me remember a few details. So for special contributions to the raw material of this book I shall mention only my former wife, Katharine Tweed, who returned to me the letters I wrote her during the war; David Grinwis, for lending me his diary of his horrifying experiences as vice-consul in Stanleyville; Barbara Rossow, widow of Bob Rossow, who likewise lent me his memoirs of his adventures as consul in Tabriz; John Waller, who enlivened our trip together in East Africa with stories of his own life as an embassy officer in Africa; Joseph “Cy” Cybulski, who provided me with forgotten details I’ve referred to in my chapter on Spain; and Anne Fischer for her help in certain “gray areas.”

I have with me, of course, a living source on all the latter part of the book, my wife, Lucky, who is an editor by training. She is at the same time an encouraging but exacting reviewer and editor of this book, which I am really writing because of her. Even though there are many pages in which I do not mention her, she is always subliminally present, my companion on the Road to Samarkand, the road she has brightened with her gaiety of spirit, her courage, and her love.

While she is my home editor, Little, Brown and Company provided me an official one, who turned out to be a real jewel. Christina Ward has guided my footsteps through the windy wastes of my early drafts. Thanks also to Deborah Jacobs, a painstaking and understanding copyeditor.

Of course I must thank George Weidenfeld, my friend of more than twenty years, who persuaded me to write this book; Leona Schecter, my literary agent; and you who read it — my heartfelt gratitude to you all.

In the true tradition of an intelligence officer, I have confined my narrative to what I saw and let you form your own opinions, rarely giving any of my own. I have viewed my role as one of telling the facts for others to study and use to make policy decisions. I make observations and try, not always successfully, not to say what action, if any, should be taken based on my findings. I’ve always been a reporter, not an editorialist.

One note, to avoid carping about minutiae: I do not follow any rules for the spelling of Arabic names. T. E. Lawrence, in his preface to The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, insists on his right to transliterate Arab names as they sounded to him as he traveled in Arabia. In the whole breadth of the Moslem world, pronunciation varies far more than in the Arabian peninsula, the scene of most of his actions. I spell the name and word often not in its official transliteration, but according to the pronunciation of the country I am visiting. Thus, the word for son can be ben, ibn, or bin, for father, Bou or Abu or Abi; the traditional headdress a kufiyya in literary style, or a chefiyya in Iraq. The letter q can be pronounced in the classical manner like a k deep in the throat, or a g in most of the Arab world, a j in Iraq, or a glottal stop in Lower Egypt and the Levant — and in Persian it becomes gh. Thus, the classical name Qasim becomes Gasim, Jasim, ’Asim, or Ghasim depending on where the man lives. The classical spelling of the name of Tunisia’s president, Habib Bourguiba, is Abu Ruqaibah! On top of all this, there are the Persian and Kurdish versions of the many Arabic names and words they have adopted. So reviewers, scholars, readers — spare this diversity. It’s part of the Middle East!

And this suggests a final tribute, one to friends and acquaintances in all parts of the world visited in my story, for their patient teaching, their warm reception of me, and their qualities as human beings — Arabs, Iranians, Jews, Kurds, Turks, Africans, Armenians, and others of all races, colors, and religions — and still others not so much part of that world, but not quite as alien as I was at first myself, a few French, many British, Spaniards, and even a Russian here and there! Let us hope that all these peoples among whom I lived will, in the wisdom of time, find a way to bury ancient hatreds, settle their feuds, and enjoy the goodness of our lovely oasis in the desert of space together in peace and happiness.

Perhaps if we can all learn the truth about each other, the truth shall make us free.

Part One

The Talents

The Ghost of Sagamore Hill

There used to be a chain in front of the driveway at Sagamore Hill. My grandmother put it there to stop the hordes of curiosity seekers who came to Sagamore, thinking perhaps that no one lived there anymore. So, grumbling, my father would stop the car to let us in, and I could, for a moment, observe from a distance the old gray house brooding in its nest of stately elms. I felt, with that peculiar instinct of a child, that this large Victorian structure had some kind of life of its own. And as we drove under the porte cockere my sense of adventure quickened, for I always anticipated these visits with an excitement the late master of the house would have appreciated. I was lucky as a small boy to spend many weeks of my summer and winter vacations at Sagamore Hill, and adventure was always there.

We were a large family he left behind. Besides my immediate family — my parents and three sisters — there were my boisterous uncles Ted and Kermit, with their wives, the brilliant and elegant Auntie Eleanor and the glamorous Auntie Belle; my fairy godmother, Auntie Ethel (Derby), and her kindly doctor-husband Uncle Dick; and the mysterious and romantic figure of “Auntie Sister” (Alice Roosevelt Longworth), who lived far away in Washington and made a brief, queenly appearance from time to time. (We never quite understood as children how an aunt could be “Sister” as well, but eventually found out that she had always been called Sister by our parents’ generation. Her real name, Alice, was never used in the family.)

…..

|