| O Enemy, the Kurdish nation

will always endure.

Not even the masters of war

will destroy it.

Let no one say the Kurds are dead …

The Kurds live. Our flag will never be lowered.

—Kurdish national anthem (by Dildar)

INTRODUCTION

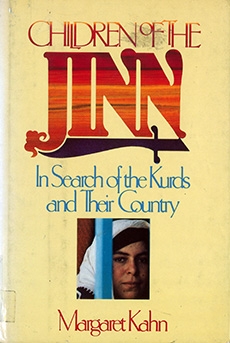

Centuries ago, Solomon threw 500 of the magical spirits called jinn out of his kingdom and exiled them to the mountains of the Zagros. These jinn first flew to Europe to select 500 beautiful virgins as their brides and then went to settle in what became known as Kurdistan. This is just one of the myths which tries to explain how such a fair-skinned, light-haired people known for their unlikely combination of ferocity and hospitality came to be living in the mountains that lie astride the borders separating present-day Iran, Iraq, Tinkey, and the USSR. Their language is similar to Persian and distantly related to English as well as to the majority of the tongues of Europe. Kurds, shut away in their mountains, did not intermarry with Arabs and Turks as much as Persians did. Maybe that is win some Kurds look Irish or even Swedish. Or perhaps it is the genes of those long-ago European virgins carried off by the jinn.

I went in search of Kurds because, to me, they represented adventure far from home and a righteous cause to believe in. I had an airplane ticket and a job waiting for me in Iran. But Kurdistan, not Iran, was my destination. There arc no maps, except those drawn by the Kurds and their friends, that read Kurdistan, Land of the Kurds. There are no signs which point the way, no tourist bureau and no guides. There arc secret police who will quickly and forcefully point sou in the opposite direction. But Kurdistan is a real place. It has its boundaries and its cities; it has its language. To find it takes time and searching—like other magical principalities in the mists of mountains, Kurdistan has a way of appearing and disappearing, opening up to an outsider and then, disconcertingly shutting itself in her face.

Many Americans and Iranians have found it difficult to understand why I decided to studv Kurdish. There is no money in it, no job teaching the language or literature the way there might be for French or Arabic, in fact, there has not been much Kurdish literature written. To many Iranians, Turks, and Arabs, Kurdish is not even a real language, but just a rustic dialect spoken by illiterates, beneath the dignitv of anyone who w'ould call herself a real scholar.

The Kurds themselves never had anv difficulty in understanding my choice of their language.

To a people fighting for their lives and control of their land, their own language is a verv precious thing. Not all Kurds arc fair with European features; some look like Arabs. Not all Kurds wear their traditional baggy trousers or many-colored dresses; some work in the citv and attend universities in Western clothes. But until now, nearly all Kurds, educated or uneducated, fair or dark, living in Turkey or Iran or Iraq or the USSR, have spoken Kurdish. Only in the last few' decades of modernization have the three governments succeeded in eroding this last and most important sign of Kurdish identity.

Kurdish clothing, jewelry, and handicrafts will come into style in Iran the way American Indian culture came into style in America—when the exotic tribal people are no longer a threat to the dominant culture. The sooner that happens, the more comfortable Iranians will be about people who want to studv Kurdish. But I didn’t want to wait until that time. It is my hope that somehow that time will never come.

Long before the shahs of Persia came to sit on their peacock throne or build the Ozymandias columns of Persepolis, the Kurds were settled in their mountains. Long before Mohammed w'as bom, Kurds embraced the Zoroastrian faith, recognizing both good and evil gods, building fire temples, celebrating the rites of Newroz, the New Day, on the vernal equinox.

When the Arabs came, most of the Kurds, like most of the Middle East, bowed to Islam. The Kurds gave Islam one of its greatest defenders—Saladin (Salah ed-Din Ayyubi), who battled Richard the Lion-Hearted and the Crusaders to regain Jerusalem in 1187. True to the times that he lived in, Saladin fought for the Muslims against the Crusaders, not for the Kurds against the Arabs.

Times changed again and, in the context of the great Islamic empires, the Kurds sought their own identity. Saladin had been theirs, but he had gained them little. Now they wanted relief from the onerous taxation of the Ottomans and recognition of their culture and language before thev were overpowered by the ubiquitous Arabic. But only visionaries like the great Kurdish poet Ahmedi Khani asked for these things in those early days. Most Kurdish leaders were holed up in their mountains, like the old Scottish lairds, fighting their Kurdish enemies, looking only to the battle and this year’s tribal victory, missing entirelv the question of Kurdish unity.

Now, like their jinni ancestors, Kurds have been trapped—not in a bottle, but in their mountains. Thev hare been excluded from many of the advantages of the twentieth centurv, remaining poor shepherds and farmers, grazing and working a difficult land with the methods and tools of their forefathers. No government has seen fit to improve their lot. Like Solomon with his jinn, these governments arc afraid of the Kurds, afraid of what they would do with a fair share of the proceeds from the oil that lies under Kurdistan, afraid of what thev would demand if they knew how to read and write and were free to speak their own language and assert their right to be Kurds. Kurds already occupy some of the most inhospitable, inaccessible terrain in the area, but the Iraqis have managed to banish them one step further: to the burning deserts in the south. Iran and Turkey have relied on psychological methods to control the Kurds, and in these countries as well, the Kurds are in constant danger of being banished—not to the mountains this time, but to being non-Kurds, stripped of their language and even of their own clothes.

In the last three decades, the Kurds have been courted and jilted by the British, the Russians, and the Americans. They have allowed themselves to be played as pawns in the great Middle East chess game in the hope of gaining autonomy as Kurds. Each great power promised them freedom when the job was finished. Each time, although they fought bravely and honorably, the Kurds have been abandoned in their struggle. No country, no matter what it promised the Kurds at the moment it decided to use them, has allowed the Kurds to fight for themselves and their dream of their own nation. Now, in the last quarter of the twentieth centurv, with American and Soviet acceptance of the regimes in Tehran, Baghdad, and Ankara, there is little interest in the Kurds and their claims.

The struggle for Kurdish self-determination keeps shifting—from Turkey in the early twentieth century to Iraq in the 1930s and ’40s, to Iran in 1946, again to Iraq through 1975, and now, finally, back to Iran. The Kurds residing in these three countries as well as Syria and the USSR outnumber the combined populations of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Yet, because of their history and their tribal divisions, the Kurds have never secured their rights. Each time, just when there seemed to be no hope left, the Kurds have risen, again and again. Each government holds the Kurds in a death grip, but when that grip weakens, even a little, the Kurds are ready to fight. As the Kurds sav, “Kurdistan ya naman”—Kurdistan or death.

What follows is the story of my search for Kurdistan in Iran of the 1970s, Iran of the shah and his secret police. When I returned for another visit in 1978, Kurdistan was more visible, partly because I knew where to look for it, partly because the shah’s power was weakening. Now the shah has toppled and no one knows exactly what will happen in Iran, especially in that unruly northwest comer which is Kurdistan. Again, as so many times in the past, Kurds are fighting for recognition and for their lives.

Part One

Outside Kurdistan

Chapter One

In Iran a woman’s clothes, especially her outer clothes, are her refuge, her shelter, a construction that tells the world she is not actually there but safe at home where she belongs. The word for veil in Persian is chador, literally a tent, and the difference between ‘being without and with a chador can mean the difference between being molested and being ignored by men on the street. A woman who is shrouded in her chador and is molested anyway has a right to be outraged. She has assumed the appearance of virtue, and in Iran appearances can be far more important than what lies beneath them.

When I first arrived in Tehran airport I was instantly surrounded by a bevv of black-tented ladies, whispering to each other and staring at me, eager for the opportunity to scrutinize a relatively naked foreign woman. Taking a cue from their behavior, I stared back, and was surprised to see the quantities of makeup on their exposed faces and the glimpses of flesh revealed by the constant readjusting necessary to keep a slippery chador around one’s body.

Although more and more modern Iranian women are throwing aside their chadors, going to work or school and walking uncovered, albeit uneasily, in the streets, the chador has been the traditional covering of Persian women for centuries. Only many hundreds of miles awav to the northwest of Tehran did I find a large group of women who have never worn the chador, women to whom the word still means a tent—a heavy piece of black homespun wool which thev must lug up the side of the mountain when the tribe moves to summer quarters. Ironically, these women wear far more modest clothing than the dress that many modern Persian women have on beneath their chadors. A Kurdish woman’s clothes …

|