|

NEW INTRODUCTION

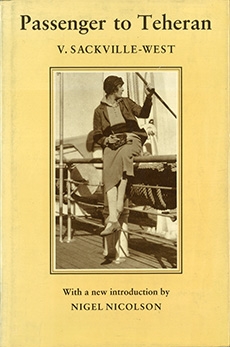

Vita Sackville-West began her book of Persian travels with the provocative statement, "There is no greater bore than the travel bore”, and then, by her account of her own journey, disproves it. Passenger to Teheran is utterly different from a returned traveller’s lecture, with slides, to a suffering audience of his friends. It gives pleasure because it describes pleasure, illuminated by what Winifred Holtby called in a contemporary review of the book, “the lucid tranquillity of her lovely prose”.

The author is eloquent about her adventures and reactions, and it would be easy to trace her route on a map, but she is reticent to the point of obscurity about her own identity, her companions on different parts of the journey and her motives for it. If one did not know that the ‘V’ of her name stood for Victoria, abbreviated by family and friends to Vita, one could be left uncertain of her sex until the very last page when she confesses, “The customs-house officer at the Dutch frontier made me an offer of marriage.” It is evident that she did not always travel alone, but the other half of ‘we’ is never identified. She speaks of diplomatic parties without saying that her husband was HM's Counsellor in Teheran, of letter-writting without revealing that her chief correspondent was Virginia Woolf, and of her 'work' without adding that she was completing in Persia her long poem The Land which is still her greatest literary testament.

In the Introduction to a new edition, published more than sixty years after the first, it is legitimate, I hope, to explain circumstances which she chose to suppress.

Vita's husband, Harold Nicolson, had won an early reputation in the Foreign Office as one of the most brilliant of its young diplomatists, becoming the pet of successive Foreign Secretaries, Balfour and Curzon, and was engaged at this very moment in writing his best-remembered book Some People. He was posted to the Legation in Teheran in November 1925 as the second-ranking officer in a small diplomatic team which included Sir Percy Loraine as Minister and Gladwyn Jebb as a young 3td Secretary. Vita refused to accompany her husband to Teheran where she would be regarded as a resident wife without any other qualification (hating to be Mrs Nicolson when she could be Vita Sackville-West, writing, gardening, at Long Barn in the Weald), but she visited him twice, because she loved him and liked the idea of Persia for its remoteness and lack of sophistication, first in 1926, the journey which this book describes, and again in the next year, when she walked with him over the Bakhtiari Mountains, an expedition which formed the substance of her second book of Persian travels, Twelve Days.

She left England on 20 January 1926 and returned in mid-May. Her journey was circuitous and leisurely, partly from choice because she had never seen India or Iraq before, and partly because travel in the Middle East by sea and land was still almost medieval in its sluggishness. Vita was accompanied as far as India by her intimate friend, the poet Dorothy Wellesley. Together they mounted the Nile as far as Luxor, and in India visited Agra and New Delhi. Vita then continued alone, by sea up the Persian Gulf, by rail to Bagdad where she stayed a few days with Gertrude Bell, and then overland by a trans-desert convoy of cars to the Persian mountains and onwards to Teheran.

It is striking how much she omits from her narrative. There is no mention of Dorothy Wellesley, much to the latter's fury. Ecstatic as Vita was about the Valley of the Kings, she made no reference to what she undoubtedly knew and saw, that Howard Carter was in the third year of his excavation of Tutenkhamun’s tomb. She allows India no more than a page, disliking it. “A loathsome place”, she wrote to Virginia Woolf, "without one shred of any quality, and I never want to go there again”, and didn’t.

“Jungle on either side of the tram”, she explained to Virginia, “rocks looking like medieval castles; peacocks paddling in the village pond. Roads tracked in the dust, seen from train windows, leading where? A jackal staring in the scrub. An English General. The Taj Mahal like a pure and sudden lyric. And everywhere squalor, squalor, squalor. Children's eyes black with flies. Men with sores. Mangy dogs. Filthy hovels not fit for pigs. And a bridge that was a concourse of men and animals and carts, all shoving, huddling, shouting, as our motor clove its way through like a snow-plough. Noise and squalor, squalor and noise, everywhere.”

Her meeting with her old friend Edwin Lutyens on the site of his half-built Viceregal house in New Delhi merits only half a line. She conceals from the reader her never-forgotten meeting with Harold at Kermanshah where he awaited her (his diary says) “in a terrible state of impatience, anxiety and excitement”, and Vita arrived, perfectly composed after a four-dav bandit-ridden journey over the Persian mountains with a saluki hound across her knees.

One would not know from her account that they lived in the Counsellor’s house in the compound of the British Legation in Teheran, the very place where Harold was born in 1886, when his father was Minister. By Persian standards it was quite comfortable. They had four servants, a stable of horses and the small fleet of Legation Fords at their command. Vita could spend part of most days as she wished, in the bazaars or in search of wild plants in,the near-desert that surrounded the city, but she did her duty, however reluctantly, as the Counsellor's wife, attending parties which tried to reproduce in the alien atmosphere of Central Asia the diplomatic civilities of Western capitals, and they bored her extremely. More for Harold's sake than for his colleagues’ she suppressed her ennui in the book, but it spilled into her letters to Virginia:

“Compound life means that at 8 a.m. the Consul’s son aged ten starts an imitation of a motor horn; that at 9 a.m. someone comes and says have I been letting all the water out of the tank; that at 10 a.m. the Military Attache's wife strolls across and says how are your delphiniums doing; that at 11 a.m. Lady Loraine appears and says wasn’t it monstrous the way the Russian Ambassador’s wife cut the Polish Charge d’Affaires’ wife last night at the Palace; that at 11 noon a gun goes off and the muezzins of Teheran set up a wail for prayer; that at 1 p.m. it is time for luncheon, and Vita hasn’t done any work.”

She minded most the indifference of rhe uprooted Europeans to Persia itself. They thought, and complained, only of its inefficiencies and discomforts, blinkered to the beauty of the country, the gentleness of its people, its gardens, literature and art. Persia had not welcomed since Curzon a more observant and appreciative British visitor than Vita. If the Persians are cruel to animals, she tells us, it is because they are “ignorant of suffering”. If she feels momentarily homesick, “sitting on a rock, with the yellow tulips blowing all about me and a little herd of gazelles moving down in the plain, I dwell with a new intensity on my friends”. When people complain that the uplands are bleak, Vitci is consoled by “the light, and the space, and the colour that sweeps in waves, like a blush over a proud and sensitive face”. Persia is full of life for those who take the trouble to seek it, “tiny, delicate and shy, escaping the broader glance”, and she was not thinking only of a gentian hiding in the shadow of a rock. She could endow these limitless plains with the personality of the humble goatherd, or the goat itself, which slowly crossed it.

From Teheran she made only one major expedition this year, to Isfahan. Harold came with her and, though she does not mention him except by the collective “we”, Raymond Mortimer, Harold’s intimate friend. They travelled through an almost deserted country in a battered car trussed with their luggage like a dromedary, slept in bare rooms and ate tinned food for want of any other thing digestible. The most eloquent section of Passenger to Teheran is Vita’s description of this trip. With admirable economy she conveys the impression of the road leading on and on to regions ever more remote, with never a suspicion that she wished she had not come. She was a born traveller, with that rare capacity to love equally letters, wrote in her diary, “She is not clever: but abundant and fruitful, truthful too. She taps so many sources of life: repose and variety.”

Returning from Isfahan to Teheran Vita helped decorate the Gulestan Palace for the coronation of Reza Khan. The ceremony is one of the set-pieces of the book, Vita as a journalist, describing the Shah as a “Cossack trooper with a brutal jaw”, which appalled Harold when the book was published, for this was the sovereign to whom he was accredited. She ends with her frightening journey home through Russia and Poland. This is Vita the adventuress and humorist. What she leaves out is the agony of her parting from Harold on the shores of the Caspian. Each felt that the absence of the other was not to be endured. But they were young, Vita 34, Harold 39, and they now had in common an experience which Vita immortalised in this book.

When Virginia Woolf read the typescript for publication by the Hogarth Press, she wrote to Vita, “It’s awfully good.... I didn’t know the extent of your subtleties ... not the sly, brooding, thinking, evading Vita. The whole book is full of nooks and crannies, the very intimate things one says in print”, but not face to face, not even in letters. Indeed Virginia was startled by her “not clever” friend’s lively, reflective prose, and one suspects, a trace jealous of it. Passenger to Teheran was written, so to speak, on the hoof, as she travelled. She could describe a scene, a person, an emotion with enviable spontaneity, plunging her hands into the treasury of the English language as greedily as into the jewel-chests of the Shah. It is a glittering book, like its contemporary The Land, both the product of her tumultuous maturity.

Nigel Nicolson

Sissinghurst April, 1990

Passenger to Teheran

Chapter I

Introductory

Travel is the most private of pleasures. There is no greater bore than the travel bore. We do nor in the least want to hear what he has seen in Hong-Kong. Not only do we not want to hear it verbally, but we do not want - we do not really want, not if we are to achieve a degree of honesty greater than that within the reach of most civilised beings - to hear it by letter either. Possibly this is because there is something intrinsically wrong about letters. For one thing they are not instantaneous. If 1 write home to-day and say (as is actually the fact', "At this moment of writing I am sailing along the coast of Baluchistan”, that is perfectly vivid for me, who have but to raise nn eyes from my paper to refresh them with those pink cliffs in the morning light; but for the recipient of my letter, opening it in England at three weeks' remove, I am no longer coasting Baluchistan; I am driving in a cab in Bagdad, or reading in a train, or asleep, or dead; the present tense has become meaningless. Nor is this the only trouble about letters. They do not arrive often enough. A letter which has been passionately awaited should be immediately supplemented by another one, to counteract the feeling of flatness that comes upon us when the agonising delights of anticipation have been replaced by the colder flood of fulfilment. Now when notes may be sent by hand, as between lovers living in the same town, this refinement of correspondence is easy to arrange, but when letters have to be transported by the complex and altogether improbable mechanism of foreign mails (those bags lying heaped in the hold!), it is impossible. For weeks we have waited; every day has dawned in hope (except Sunday, and that is a day to be blacked out of the calendar); it may have waned in disappointment, but the morrow will soon be here, and who knows what to-morrow’s post may not bring? Then at last it comes; is torn open; devoured; - and all is over. It is gone in a flash, and it has not sufficed to feed our hunger. It has told us either too much or too little. For a letter, by its arrival, defrauds us of a whole secret region of our existence, the only region indeed in which the true pleasure of life may be tasted, the region of imagination, creative and protean, the clouds and beautiful shapes of whose heaven arc destroyed by the wind of reality. For observe, that to hope for Paradise is to live in Paradise, a very different thing from actually getting there.

The poor letter is not so much in itself to blame, - and there is, I think, a peculiar pathos in the thought of the writer of that letter, taking pains, pouring on to his page so much desire to please, so …

|