| Introduction

ONE CHILLY FALL night in 1978, a small group of university drop-outs and their friends gathered behind blacked-out windows in Turkey’s southeast to plan a war for an independent Kurdish state. Driven by their revolutionary zeal and moral certitude, the young men and women did not see any serious barriers to their success. But outsiders might have been forgiven for thinking otherwise. Turkey’s military had hundreds of thousands of experienced soldiers. A NATO member, its government was a close ally of the United States and its armed forces recently had showed their fortitude in the swift occupation of northern Cyprus. It was no wonder that those who tracked radical groups dismissed the newly founded Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) as nothing more than thrill-seekers or brigands.

Within a few years these pronouncements would be proven very wrong, as the PKK swept to dominance and radicalized the Kurdish national movement in Turkey. The small group of armed men and women grew into a tightly organized guerrilla force of some 15,000, with a 50,000-plus civilian militia in Turkey and tens of thousands of active backers in Europe. The war inside Turkey would leave close to 40,000 dead, result in human rights abuses on both sides, and draw in neighboring states Iran, Iraq, and Syria, which all sought to use the PKK for their own purposes.

Turkey’s capture in 1999 of PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan, coupled with his subsequent decision to suspend the separatist war, was hailed as a great victory for Turkey and in the initial euphoria it was easy to believe the rebel group had collapsed. But the end of the war did not mean the end of the PKK nor the end of Turkey’s Kurdish problem. The PKK, which for more than a decade had been the dominant political organization of Turkish Kurds, maintained its controlling power and influence. And Turkey, by its unwillingness to seriously address Kurdish demands, despite the new peace, kept the Kurdish problem alive.

In 2004, the PKK regrouped its forces and called off its lopsided ceasefire. By 2006, clashes again were rising and so was the death toll on both sides. The rebels had many reasons for returning to battle: it was a response to Ankara’s political inaction; it was a way to ensure that the PKK remained relevant and in control; and finally, there was Iraq to consider. The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 had given Iraqi Kurds an unprecedented chance to rule themselves—and they grabbed it. While the rest of Iraq stumbled toward civil war, Iraqi Kurds, who comprise about five million of the country’s 26 million-strong population, withdrew into their relatively homogeneous enclave in the north. With grudging approval from the United States, which was loathe to oppose its one real ally in Iraq, the Kurds laid claim to autonomy and received formal backing for this in Iraq’s new constitution late in 2005. Iraqi Kurdistan, as it is now known, has its own parliament, its own flag, its own army, and its own investment laws to regulate oil resources, making it look very much like the independent state that Kurds in Iraq, like many of those in Turkey, had long hoped for. And the PKK, once viewed as the dominant Kurdish group in the region, suddenly was afraid of slipping behind.

If there is one thing that all the countries in the region agree on— and the United States, too—it is that an independent Kurdistan is a bad idea. An Iraqi Kurdish state would splinter Iraq, leaving other ethnic and religious groups free to wage a violent battle for control of the rest of the country and its rich oil reserves. Turkey, Iran, and Syria, all of which border on Iraq, have other concerns: They face their own nationalist Kurdish movements, some of them armed. A Kurdish state in northern Iraq would embolden Kurdish activists everywhere.

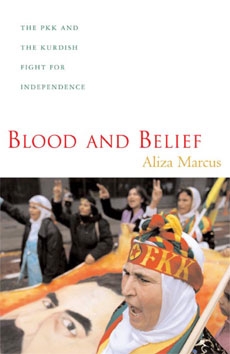

The repercussions of the Iraqi Kurdish ministate —even one that is not officially independent, not yet— are rippling across the region. And no more so than in Turkey, where Kurds number some 15 million, making up about 20 percent of Turkey’s 70 million population. PKK supporters are again taking to the streets with posters of Ocalan and leaving for the tough mountains on the Turkish-Iraqi border, where the rebels have their mobile camps. This time, the war may be even bloodier. A new urban militant wing, the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons (TAK), targets Western cities and tourism resorts. Its attacks are more frequent and professional than those staged in the 1990s. For the first time, there is a real danger of civil violence between Kurds and Turks in the country’s urbanized, Western centers.

Things are growing more tense in other countries where Kurdish minorities have long been discriminated against or oppressed. In Syria, where Kurds make up about 10 percent of Syria’s 18 million population, violent clashes have broken out between the security forces (and Syrian Arab crowds) and Kurds living there. The Syrian Kurds once gave their loyalty to the PKK, but this ended when Ocalan was kicked out and the group’s activities shut down. Now, bereft of active representation and without much hope for democratic change, Syrian Kurds have turned more vocal. They may not want their own state—at least not yet—but they do want political rights and ethnic-based rights. These are demands that threaten the very foundation of the Arab nationalist, authoritarian Syrian state.

The situation is not that different in Iran, where Kurds make up some 7 percent of Iran’s 68 million people. Kurdish activism in Iran surged following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, as Kurds held noisy demonstrations in favor of the political gains made by their ethnic kin in Iraq. The PKK used to ignore Iranian Kurds—part of its deal for getting Iranian backing in the 1990s—but Tehran cut the support when Ocalan was captured. Now, the PKK is actively wooing Iranian Kurdish support. And Iranian Kurds, whose demands for political freedoms have long been ignored by the Islamic regime, are listening. A PKK-affiliated party for Iranian Kurds—PJAK, or the Party for Free Life in Kurdistan—is based alongside the PKK in the Kandil Mountains in northern Iraq. Its armed forces have become an effective irritant to Iranian troops, which in mid-2006 began carrying out brief armed incursions and shelling the mountain range to drive out the rebels.

The U.S. struggle to stabilize Iraq and bring democracy to the re-gion is forcing the international community to pay attention. The Kurds are the world’s largest stateless people and nearly half live in Turkey, making the battle there a crucial part of the larger Kurdish problem throughout the region. Understanding the PKK—and the de-mands of Kurds in Turkey—is key to understanding the challenges the United States faces in formulating stable policies in this troubled part of the world. The crisis in Iraq and tensions over potential Kurdish separatist interests there underscore that the region’s some 28 million Kurds will long remain a source of instability for the governments that rule them and the Western powers that try to influence events there.

When I first traveled in 1989 to the remote mountain region of Sirnak, center of the PKK fighting in southeast Turkey, few foreign reporters had written in any detail about the Kurdish confict in Turkey. It was just a year since Iraqi President Saddam Hussein gassed his own Kurdish population in the village of Halabja, but even that had not sparked much interest in the bitter battle underway across the border. The main reason was that when Kurds weren’t being killed by the thousands—as happened in Halabja—the West didn’t care. The Kurdish confict seemed as remote as the region where they lived, a treacherous terrain intersected by the borders of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. And the Kurds themselves were difficult to understand. Divided by borders, dialects, tribal loyalties, and blood feuds, it was easy to dismiss their uprisings as the machinations of gun-toting brigands suspicious of the central authority.

I remember the ride over a rutted dirt-packed road to get to the village of stone and mud houses, where a small gravestone marked the spot of a young PKK rebel, a girl. Her name was Zayide and she had been killed in a battle with the Turkish military. The people told me that when the army tried to bury her in a hidden spot outside of the village, their bulldozers could not break the ground. Three times they tried and three times they failed. The people took this as a sign that Allah was protecting the girl—and the PKK’s struggle—and the military finally turned the body over to the girl’s family for burial. Her small grave had become a shrine of sorts, where women especially came to pray for help in finding husbands and for fertility. Seeing this, I resolved to learn more about this group that, despite its brutality against its own members and bloody attacks on Kurdish civilians, managed to claim the loyalty of the majority of Kurds in Turkey and many in Europe. Over the next seven years, I traversed southeast Turkey and northern Iraq in search of stories, sometimes working as a freelancer and later as a staff reporter for Reuters news agency.

In 1995, in my second year as an Istanbul-based correspondent for Reuters, the Istanbul state security opened a case against me. The charge was “inciting” racial hatred and the crime was an article that described how the Turkish military was forcing Kurdish civilians out of their villages to deny the rebels support. The article had been used by a Kurdish newspaper in Turkey—the newspaper, like many others in Turkey, subscribed to the Reuters news service—which made it possible for the court to charge me. No-one ever suggested the article was false, just that it would have been better had it not appeared. I was acquitted, but Turkish authorities insisted I stop working in Turkey and Reuters subsequently transferred me to the their Middle East/Africa desk in Nicosia. I returned to Turkey many times, some-times for work, other times to see friends, but to avoid problems with the authorities I avoided reporting on the Kurdish conflict in the southeast.

The idea for this book came to me after Ocalan was captured, when PKK rebels began to split from the group in frustration with Ocalan’s new, more compliant stance and his call for the rebels to disarm. For the first time, well-known militants, often dispirited and coming to grips with their own past, were willing to talk. For the first time, it was possible to get detailed information directly from those who had been inside the group, without relying on Turkish army statements or statements by PKK militants in Turkish custody. Despite concerns I had about returning to this subject, I could not give up the chance to get the inside details about the PKK, a group about which I had written many articles, yet almost always based on information from civilian supporters and Turkish opponents.

I hope this book will make the Kurdish war in Turkey and the Kurdish conflict throughout the region more understandable. And along the way, help explain what causes a 16-year-old girl named Zayide to leave her family and friends and join a rebel war that, as she must have realized, was likely to lead to her death in a year or two.

Washington, DC, December 2006 |