| Preface

Turkey is a "state of law," its leaders repeat. This would be good news if the facts confirmed such declarations. Unfortu- nately, the news that reaches us is rather bad.

An anti-Kurdish policy is still in effect in Turkey. Members of parliament are arrested. Intellectuals are threatened, brought before the courts, sentenced, and efforts made to silence them.

The worst is seen in the shocking numbers: in its December 11, 1994, editions the daily Turkish newspaper Milliyet reported that 3,840 people had died under torture or following extrajudicial executions during the past two years.

For the first time in' October 1994, an official in the Ankara government—the Turkish minister of human rights, Azimet Koyluoglu—did not hesitate to call the military operations that took place in the Tunceli province in eastern Turkey "state terrorism." That same person—in an interview published by Cumhuriyet, the major Turkish daily—asserted that 1,390 villages and hamlets had been evacuated by force in southeastern Anatolia (heart of Turkish Kurdistan) and that 2 million people were homeless at the borders of Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

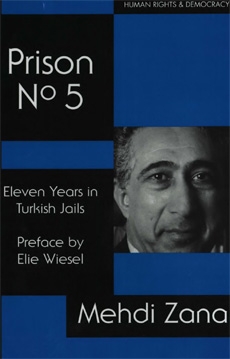

Diyarbakir, the principal city of Turkish Kurdistan, of which Mehdi Zana was once mayor, saw its population grow from 400,000 to more than 1 million people, due to the influx of refugees driven out of the neighboring countryside. Overwhelm- ing on a political scale and humanly intolerable, this desperate and appalling testimony of the Kurdish leader Mehdi Zana is especially so when it discusses the recent history of the 1970s and the 1980s.

I admit having read this book with a heavy heart, vacillating between a cowardly skepticism and an active anger, for I had another idea about Turkey. Had it not opened its doors to Sephardic Jews driven out of Spain in 1492? Had we not justly praised Turkey for its philosophy of tolerance toward religious and ethnic minorities? Was Turkey not for many of us the freest nation in the Muslim world? Every time I have criticized one of its decisions—for example, concerning the memory of the Armenians or the destiny of the Kurds—Turkish officials and Jewish friends from Istanbul did all they could to make me understand my error of judgment. When I insisted, they replied, "It's a matter of terrorists; doesn't a state have the right, if not the duty, to defend itself against murderous violence?"

But then how does one explain the account of Mehdi Zana, arrested, tortured, and then sentenced for his loyalty to his Kurdish brothers? What does he say? What does he ask for? "What we are asking for is the right to speak our own language, to learn it in the school, and to have newspapers and radio and television broadcasts in Kurdish. We want to live as complete human beings, with respect for our dignity and identity. This is why we are imprisoned, why we are tortured, and why we are killed."

Should we still doubt? Yashar Kemal, the great Turkish novelist, knows Mehdi Zana very well and assures me of Zana's complete honesty: "He is not a man who lies." Two thousand Kurdish villages were destroyed by the army, according to Kemal, who published courageous articles denouncing his country's policy against the Kurds.

Mehdi Zana is still young, in the prime of his life. He is in his mid-50s. Only, he does remember, and he forbids us to forget that he spent fifteen years in prison. He brings out memories that are hard to swallow, they are so atrocious and barbaric.

Solitary confinement, guards' insults, the obligation to salute the captain's dog, the beatings, the sleep deprivation, the falaka, the fainting, the trampling, the electrodes attached to genitals, German shepherds trained to bite the private parts of naked prisoners. How does one understand? How can we explain the institutionalization of these brutalities, this humiliation, this dehumanization?

Is it possible that this happened just recently in Turkey, in the West, in a country that is a member of NATO? For a long time in order to repress the nationalist Kurdish spirit, denying the right of the Kurdish community its cultural identity, the government tried to stifle even the Kurdish language. To speak Kurdish was a crime punishable by imprisonment.

Officials and their supporters have told us that the Turkish government is obliged to combat Kurdish nationalists. This is based on the pretext that they are separatists and secessionists and that their true goal is to found an independent Kurdish state.

Mehdi Zana and his friends assert the opposite. According to them, the Kurds aspire only to preserve their cultural heritage and their ethnic identity. In all of their declarations, they assert that the Kurdish problem must be settled within the existing borders of Turkey.

But the Turkish penal code likens such declarations to the crime of separatism as soon as they assert the very existence of a Kurdish people in Turkey. In May 1994 Mehdi Zana was thus sentenced again to four years in prison on account of remarks he had made in the fall of 1992, first at a press conference and later before a European Parliament subcommittee on human rights.

For the same reasons, eight members of the Turkish Parliament were sentenced in December 1994, to varied prison terms: five, including Leyla Zana, the wife of Mehdi Zana, were sentenced to a term of fifteen years. President Mitterand, Jacques Delors, the European Parliament, the U.S. State Department, and many others protested against this shameful act.

Yashar Kemal, who was present at a number of the hearings, declared before the verdict was announced, "This trial is a disgrace to humanity. If the members of Parliament are sentenced, Turkey will enter the twenty-first century cursed. I am here to protest against the Council. of Europe and the UN, which are equally responsible for this situation. This trial is possible only with their support. They are equally responsible for the filthy war that continues in the southeast [Turkish Kurdistan]. In this trial it is the Turkish people and democracy which are judged."

Why do the Turks and Kurds not meet around a table in order to discuss their differences? Why do they not follow the example of the Israelis and Palestinians, who knew to choose negotiation rather than armed struggle? Those who know the prime minister, Ms. Tansu Çiller, describe her as liberal and courageous. Will she know how to hold out against the military, which seems to hold the true power in the country? We hope that she can. Her people deserve it.

Elie Wiesel

Paris 1994

(Translated from French in 1997

by Sarah Hughes)

Postscript

MehdiZana has been a major actor in the past thirty years of Kurdish history in Turkey. Without a doubt, his destiny, more than that of anyone else, illustrates the chaotic development of this period created by tenacious combat for the recognition of the existence of Kurds. Their hopes for emancipation and democracy have been shattered by military coups and subsequent waves of mass repression aimed at suppressing democratic opposition and eliminating the Kurdish political elite.

This singular destiny is a witness to the difficulty of being a Kurd in Turkey and of claiming, even peacefully, the rights of an indigenous people who make up at least one-quarter of the country's population. Following World War I, the Kurdish people were tom apart and scattered among Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, where imposed nationalist dogma, dominant and intolerant, denied their very existence.

This negation of the Kurds has been inscribed in successive Turkish constitutions and laws. The questioning of this negation is sanctioned by punishments ranging, according to conjecture, from a few years in prison (generally accompanied by a variety of tortures, professional prohibitions, diverse economic and administrative forms of harassment, temporary or permanent deprivation of civil rights) to sheer physical elimination.

The protection of the founding myths of the Republic is paramount in the Turkish political system. This system, since its establishment on the rubble of the Ottoman Empire, considers itself as a unitary nation-state with a single people, a single language, and a single culture. In this country, descended from a colonial empire of great ethnic and cultural diversity, no community, except for small Christian and Jewish religious minorities, can claim specific collective rights. This nationalist ideology, called Kemalism (after its founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, “Father of the Turks”1), is erected in a true state religion, in which worship is carefully maintained and inculcated through a series of institutional reinforcements (such as the army, schools, universities, and the media). Kemalism is often presented by its Western followers, seduced by its modernizing and secular aspects, as an eastern avatar of Jacobinism,2 whereas the elite Turkish nationalists consider it to be the cement unifying their state. Calling it into question is as intolerable for Turkish authorities--depositories of the dogma, in particular the army, the appointed guardian of the Kemalist temple, and its auxiliary, the omnipresent MIT (Turkish Intelligence Agency)-as was calling into question Marxist and Leninist thought in a communist country.

It remains nevertheless true that this fiction of cultural homogeneity and linguistic uniformity is incessantly contradicted under various forms by its victims-the numerous non-Turkish populations living in Turkey: Lazes, Arabs, Circassians, Azeris, and Kurds. The latter, due to their vast numbers, to their very strong self-identity, and to the existence of substantial Kurdish communities in the neighboring countries, without a doubt form the first stumbling block to the plan to create a Turkish nationalist project of "cultural and linguistic homogeneity in the country."

The Kurds have a unique language, unrelated to Turkish, and a culture and a civilization that are rich and ancient. The Kurds do not consider the Turkish culture to be superior to their own, and, in their immense majority, they have no desire to renounce their own identities and to let themselves be "turkified." For this reason, attempts aimed at assimilating Kurds, despite the diversity of the means used, have ended in failure.

Well before the Kemalists, their Pan-Turanian3 precursors of the Union and Progress Committee (UPC), who came to power in favor of the "Young Turks" revolution of 1908, realized that Kurds and Armenians were an obstacle to fulfilling their dream of a Turkish Empire extending from the Balkans to central Asia, because their populated regions prevented the territorial continuity of Turkish-speaking worlds of Anatolia and Asia. These Pan- Turanians therefore decided to eliminate these undesirable populations through massive deportations.

During World War I 1.5 million Armenians and approximately 700,000 Kurds were deported; a great number of them were massacred, based on this policy. This, however, did not deter a number of traditional Kurdish chiefs, beginning in 1919, from rallying around the Turkish general Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who held himself out as a new man and who promised to create a “Muslim state of Turks and Kurds” on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. To lend some substance to his promise, the Turkish leader had seventy- five key Kurdish figures seated in the National Assembly in Ankara as "representatives of Kurdistan" and presented them, on February 10, 1922, with a proposed set of nineteen articles dealing with the creation of a "Kurdish province and assembly."

The goal of this maneuver was to convince the Kurds that they would be able to enjoy all of their rights while remaining allies of the Turks and thus that it was therefore not necessary for them to join the partisans of the Treaty of Sevres4 in 1920, which advocated the creation of an Armenia and a Kurdistan but was unfair and humiliating for the Turks. In order to free their country from occupation, Turks needed the support of Kurdish forces, support that was largely given to them.

However, once Turkish independence was acquired, after a few battles led against Greek troops resulted in fewer than 10,000 deaths, and was recognized internationally by the Treaty of Lausanne in July 1923, the Turkish leaders quickly reneged on their promises to the Kurds. These promises that turned out to be nothing more than wartime tricks in the centuries-old Turkish political tradition. In a decree entered on March 3, 1924, the Grand Assembly was dissolved. Its lawmakers from Kurdistan, who had believed in the "obligation to come to the aid of their Turkish brothers in distress," were all, under diverse pretexts, sent to the gallows by the dreadful “independence courts.” These courts were the precursors to the current State Security Courts, before which other Kurdish members of Parliament (including Mehdi Zana's wife, Leyla) were sentenced in 1994 to up to fifteen years imprisonment for their political beliefs. When this decree was entered, the constitution was abolished and replaced by a new text that consecrated the nationalist orientations of the Turkish Republic. The language and more generally all manifestations of the Kurdish identity-schools, associations, and Kurdish publications-were prohibited. The words Kurd and Kurdish were banished. Turkey committed itself resolutely to the construction of a unitary nation-state having as its goal the disappearance, in the name of modernity and nationalism, of its ethnic and cultural diversity.

The Turkish minister of justice, Mahmut Esat Bozkurt, summarized the ideology of the new Turkish state in these terms: "We live in the freest country in the world, which is called Turkey. The Turk is the only lord, the only master of this country. Those who are not of purely Turkish origin have only one right in this country: the right to be servants, the right to be slaves."5 The Kurdish reaction to this "treason against Mustafa Kemal" was a disorderly armed revolt. The Turkish regime quickly found a pretext in this revolt for suppressing the Turkish liberal opposition, labeling it as "cosmopolitan, antinationalist, and reactionary."

The government also seized the opportunity to resume its project of dispersion and forced assimilation of Kurds, who, since the disappearance of the Armenians and the expulsion of 1,200,000 Greeks from Anatolia to Greece, comprised an intolerable people with a distinct culture in a Turkey that wished to be the country of exclusively "pure Turkish race."

In this cycle of repression-revolt-repression, from 1925 to 1938, Turkish Kurdistan lost a third of its population; that is, approximately 1.5 million Kurds were uprooted from their land, deported, and partially massacred. On May 5, 1932, a law on the dispersion and deportation of Kurds6 was promulgated in order to legalize this policy of "dekurdisation" of Kurdistan and the elimination of the Kurds as a distinct people. The culmination of this undertaking of destruction was achieved in 1937-1938, when tens of thousands of peasants from the Kurdish province of Dersim died under Turkish aerial bombardments, were burned alive in their villages, or were shot summarily. In 1940 (the year in which Mehdi Zana was born), World War II forced the Turks to suspend their operations in Kurdistan.

The massive and blind violence and the massacres intended to terrorize the populations whose submission they wanted are a part of the long Turko-Mongolian state tradition. Men like Attila the Hun, Genghis Khan, and Tamerlan, abhorred in the West as bloody savages, are extolled in Turkey as "national heroes." The same is true for the Turkish Sultan Selim the Cruel, who, just before the Persian campaign in 1515, put 40,000 innocent civilian Shiite Muslims to the sword simply to make his adversary think twice. It is also the case of the triumvirate that directed the Ottoman Union and Progress Govemment-Enver, Talat, and Djemal-authors, among other crimes, of the Armenian genocide. In a culture in which one continues to think that "a thrashing comes directly from heaven" and that "the horse belongs to he who mounts it, the sword to he who carries it"-a culture in which one never ceases to inculcate, starting at early childhood, the worship of strength and faith in the army-the use of terror as a method of governing is not considered an anomaly. The democratic culture is still embryonic in Turkey. For Turkish citizens the state is not only a tool to serve the people, destined to ensure its protection, guarantee its liberty, and take responsibility for its administration. The Turkish state, Dev/at Baba (father-state), is also an eastern bogeyman with unlimited rights, inalienable and unquestionable with respect to its progenitor. The Turkish father-state must, before all, make itself respected, show that it is all-powerful, and make itself feared. Fear, of which the army is the institutional dispenser, is present at all levels of society, including the most powerful civilian political leaders. The importance of this army of eight hundred thousand men is excessive, given the size of the population and the modest economy of Turkey. It emphasizes the key role given to the military in the Turkish regime.

More than in the short war of independence with the Greeks, it was in the military campaigns led against the Kurds from 1920 to 1930 that the new Turkish army was forged. These campaigns certainly did not succeed in eradicating or in solving "once and for all" the Kurdish problem, following the example of the Armenian problem. Nevertheless, they permitted the extermination of Kurdish leaders and a bleeding of the Kurdish population such that it required at least a generation before it raised its head and claimed its rights again. This awakening process, initiated by the Iraqi revolution in July 1958 and proclaiming "equality and brotherhood of the Arab and Kurdish nations freely united in the Iraqi Republic," was followed by broadcasts in Kurdish from Radio Baghdad and Radio Erevan (then capital of Soviet Armenia) that at first reached only a small circle of intellectuals united around the writer Musa Anter. Starting in 1959, long before the military coup of May 1960, about fifty Kurdish intellectuals were arrested and incarcerated in a military prison for "separatist activities." These activities generally consisted only of possessing a text or a recording of Kurdish music, if not more than a private conversation in Kurdish at a university or in university dormitories.

The military regime of General Gursel accused the civil government of Adnan Menderes, which it had just overthrown, of "complacency toward the separatists" and launched its famous "Citizen, speak Turkish" campaigns in the Kurdish provinces while erecting statues or busts of Atatürk in the smallest towns and villages. The two favorite slogans of this campaign were "A Turk is worth the universe" and "What a joy to say you are Turkish," articles of faith in Turkish nationalism, inscribed in giant letters on the mountainslopes of Kurdistan, while general Gursel declared in Diyarbakir, "Spit in the face of he who calls you Kurdish."

A short time after the military coup, following the adoption of a new constitution and the return to a civil government, the Kurdish prisoners and internees were freed. It was an extraordinary event in the history of the Turkish Republic to see Kurds who had been prosecuted for separatism get out of jail alive. From then on it became possible to defend Kurdish rights for the price of a few months or a few years of prison. This gap that had just enlarged in the wall of fear and the development of a legal socialist left defending the ideas of social justice, of freedom of press and thought, and of political and cultural pluralism contributed to awakening Kurdistan-a region forbidden to foreign visitors until 1965-from a long night of silence. This movement of a core of intellectuals gradually spread to the urban middle class and to the recently urbanized peasants.

General Barzani's struggle for Kurdish autonomy in Iraq echoed through the media and also gave courage to the Kurds of Turkey, who had been humiliated for so long. The revived Kurdish policy was translated, in a diffused and prudent way, by the support given to the New Turkish Party of Dr. Yusef Azizoglu, a parliamentary representative from Diyarbakir who made the development of the eastern (Kurdish) provinces a priority, and by the development of the Turkish Workers' Party, which, while recognizing the legitimacy of the identity claims of the Kurds, subordinated their satisfaction to the social emancipation that would follow the arrival of the left to power. Wanting to free themselves from the restrictive legal setting, certain Kurdish intellectuals had created the Kurdish Democratic Party of Turkey (KDP-T), modeled on Barzani's KDP.

At the crossroads of these movements was Mehdi Zana, a young tailor eager for knowledge and action. He frequented working- class leftist intellectual and nationalist circles and populist milieus. Choosing the legal left for advancing Kurdish demands, he sought peaceful and democratic struggle and led by personal example, ultimately paying for it with his own body. He was one of the principal organizers of the "meetings of the East." These large and peaceful popular rallies in 1968 in Silvan expressed for the first time in public the cultural, social, economic, and political claims of the Kurdish population. The younger generations, overcoming their elders' fear of the state, committed themselves with passion to these new forms of activism. The overwhelming success, and especially the perceived potential of this popular phenomenon, incited the Turkish regime to counterattack by putting political and security measures into effect. Cities that were deemed "centers of agitation" –starting with Silvan and Batman-were surrounded by the military forces. The inhabitants were rounded up in public squares and collectively beaten and humiliated, their houses thoroughly searched to show that the army was still present and that everyone had to remain peaceful. In short, the military tried to intimidate and terrorize the population in order to eliminate any nascent desire of the Kurds to publicize their demands.

Politically the response was varied. Realizing that the official nationalist ideology was unappealing, the Turkish authorities favored the development of religious brotherhoods and Islamic networks to counter Kurdish nationalism. At the same time, in the cities of mixed Kurdish-Turkish or Sunni-Shiite populations, the regime imposed the Nationalist Action Party of the Turkish colonel of the extreme right, Alpaslan Türkes, in order to have at its disposal a local Turkish organization, should the need arise.

Finally, in order to divide and neutralize the left, the political police (PIT) encouraged the small groups that resorted to armed struggles. Their first actions obviously served as a pretext for a new armed intervention on March 12, 1971.

According to the classic and well-run scenario of these coups, "in order to save the country from chaos and to ward off the separatist peril," the constitution was amended to be more repressive, political parties and labor unions were suspended, the directors and activists of leftist organizations were arrested, and a series of publications and books were banned, pulped, or burned. In this way the Turkish Workers' Party was dissolved in June 1971 for having recognized, in a resolution of its fourth congress, "the existence of a Kurdish people in the east of the country." Its principal Turkish directors, including Behice Boran, were sentenced to twelve years in prison for "separatism." Approximately 2,600 Kurds were arrested and incarcerated at the time of the coup. But with a few exceptions, they were not tortured. Sentenced to long prison terms, they were all freed in July 1974, owing to a general amnesty decreed by the new center-left government of Bulent Ecevit, who, just before the invasion of Cyprus, wanted to present an open and democratic image of his country, in contrast to Greece, under military rule.

In one decade the number of incarcerated Kurdish activists grew from a few dozen to 2,600 -an effort by the Turkish authorities to temporarily remove the leadership of the Kurdish movement. In the following coup, in 1980, the government arrested or placed in custody hundreds of thousands of Kurds, who upon their freedom from prison refused to "settle down" but instead resumed the struggle to obtain the rights of their people.

That is what Mehdi Zana did in 1974, after having spent three years behind bars. Having participated in the rebirth of the Workers' Party, in which he had been a member of the central committee, and while continuing his profession as a tailor, he supported the Kurdish leftist intellectuals, grouped around the two publications Özgürliik Yolu (The Path to Freedom) and Roja Welat (TheDay of the Country). Then, in December 1977, without any money in either his pocket or the party apparatus, supported by friends full of goodwill but just as impecunious, he ran as an independent candidate in the election for mayor of Diyarbakir, the political and cultural capital of Turkish Kurdistan. Leading his campaign entirely in Kurdish in working-class towns, he ran as a Kurdish candidate of the left, fighting both for the rights of Kurds and for social justice. He was ahead in an election in which there were no fewer than eleven candidates. Thus for the first time in the history of the Turkish Republic, a Kurd openly claiming his identity was elected mayor in a large city (two hundred twenty five thousand inhabitants), despite maneuvers and various methods of intimidation by the police and the army.

Surprised by the election verdict, the Turkish government resolved to thwart this experiment, which it judged dangerous by its popularity. However, supported by the leftist press, a few democratic civil servants, and the population of his city, the new mayor succeeded in loosening the government's grip, working twice as hard in order to bring basic municipal services-such as refuse collection, main sewers, and electricity-which until then had been denied-to the disadvantaged working-class neighborhoods.

What remained insoluble was the problem of public transportation. The government had refused Mehdi Zana the authorization to acquire from abroad buses, which Diyarbakir badly needed. Alerted by my concerns, the French socialist mayors agreed to invite him to France and to help this "socialist democratic mayor, so rare in the Third World." In a few months the solidarity of such cities as Bayonne, Brest, Clermont-Ferand, Grenoble, Montpellier, Nantes, and Rennes made it possible to send a convoy of approximately thirty buses and commercial vehicles to the besieged Kurdish capital. This action comforted the Kurdish population; but the Turkish authorities, very unhappy, saw signs of a "Western plot" aimed at encouraging Kurdish separatism. (At each of his torture sessions during all the years of his detention, the Turkish torturers interrogated Mehdi Zana about his "foreign connections" and about his "Western separatist henchmen.")

Already guilty of being Kurdish and socialist, Mehdi Zana scoffed at the authorities and thwarted their calculated moves by addressing himself directly to the Western democracies. He thus became, in those years when one did not yet talk about the likes of "terrorism," the enemy of choice of the prickly Turkish nationalism. But although a number of Kurdish militants were assassinated or disappeared in mysterious "road accidents," according to the traditional policy of eliminating Kurdish elites, the mayor of Diyarbakir, surrounded by faithful and devoted friends, was able to survive. His notoriety, at home and abroad, undoubtedly also protected him, which only stirred up the hatred of policemen and Turkish soldiers, who dreamed of the moment when they would at last be able to settle their accounts with him.

The moment presented itself with the coup of September 12, 1980, which occurred just days after the start of the Iran-Iraq war. One of the war's first theaters of operation was along the 500-kilometer border between Iranian Kurdistan and Iraqi Kurdistan. In fact, earlier, when the Iranian monarchy fell in February 1979 and a powerful autonomist movement, led by a moderate Kurd, Abdoul Rahman Ghassemlou, emerged, the Turkish military leaders, believing that Turkey was headed for trouble and that the solution required a strong power at the head of state, decided to intensify the strategy of tension put into place in 1978 by the Special War and Counter Guerrilla Headquarters in order to prepare for a new armed intervention. Thanks to the know-how of these services, blind violence resulted in some twenty deaths per day, sowing insecurity even in the hearts of large cities. In this well-prepared climate of terror, the coup was met with relief by a segment of the population and by numerous Western capitals, including Washington, Bonn, and Paris. A number of commentators, not always with bad intentions, willingly presented the affair

as a "prophylactic action by the army, which remains dedicated to pluralist democracy and which will retreat to its barracks after having put the house in order."

This "order" was imposed at the cost of the largest police raids in the history of the Turkish Republic. In its December 12, 1989, 'issue, the daily Istanbul newspaper Cumhuriyet-the Turkish equivalent of the Washington Post-assessed the situation, reporting that six hundred fifty thousand people were in police custody and that proceedings had been held against two hundred ten thousand people following their detention. (See Appendix A for a summary.) In a study entitled Unfair Trialfor Political Prisoners in Turkey (EUR 44/22/86), Amnesty International concluded that "more than forty-eight thousand political prisoners judged by military courts since the first declaration of martial law in December 1979 have been sentenced to prison terms or capital punishment after unfair trials."

The military regime made a tabula rasa of the civilian society, dissolving all political parties, trade unions, and associations. The constitution was abolished, public liberties were suspended, and even traditional political figures, including Prime Minister Demirel, were interned. The city council was also dissolved and the mayors replaced by military officers. A new constitution, custom made and designed to ensure the continuity of the military power, was promulgated in 1982. Its preamble? legitimizes the coups and consecrates as official state ideology "the principles and reforms of Atatürk, the immortal guide and incomparable hero." This ideology was founded on the negation of the Kurdish people's existence, culminating in legislation on prohibited languages8 that equated the use of the Kurdish language to an attack on the unity of the state. The preeminence of the army in political life is made official, due notably to the National Security Council.

Made up of five military leaders (the President of the Republic, the Prime Minister, and the ministers of Foreign Affairs, Defense, and the Interior), the council is the effective government of the country, and its recommendations have always been and always will be followed by the government and Parliament.

When state violence reaches such large scales, should one still talk about repression? It is no doubt more appropriate to talk about war, an undeclared war by the state against a large segment of its population. This war, or state terror, was particularly savage and massive in Kurdistan, where thirty cities and thousands of villages were wiped out. The best-known Kurdish militants, including a number of mayors, deputies, and lawyers, were incarcerated in the military prison in Diyarbakir, where the most barbaric methods of torture were systematically applied in order to physically and psychologically break the Kurds. Sixty-five Kurdish militants died under torture at Diyarbakir. Others perished in Ankara and Istanbul. Thousands of militants were mutilated and will always suffer from the aftereffects of their years in this prison-hell designed to humiliate, degrade, dehumanize, and terrorize. Two survivors of this hell, Serafettin Kaya and Htiseyin Yilidirim, published their unbearable testimony in Turkish. As to that of Mehdi Zana, his testimony appeared in its entirety under the title Vahsetin Giinlügü (Diary ofBarbarism9). The essence of this testimony, without the horrible details of all of the cruelty to which he was subjected, is in the form of interviews, in the abridged version that the author gives here.

Nothing, no crime of any seriousness whatsoever, can justify state use of equally degrading and debasing conduct. The fact is that Mehdi Zana never committed any reprehensible act. His only "crimes" are being Kurdish, having spoken Kurdish to his administrators, and having peacefully demanded cultural and political rights for his people. He acted in broad daylight, advocating democratic debate and dialogue in order to advance his cause. A man of peace in favor of coexistence, equality, and democracy for the Kurdish and Turkish peoples, he always took exception to resorting to violence. For this he was quickly adopted by Amnesty International as a "prisoner of conscience."

The International Federation on Human Rights, in the presence notably of Claude Cheysson and Robert Badinter, dedicated its 1986 Paris conference to Mehdi Zana. An international campaign begun to ensure his freedom. From François Mitterrand to Willy Brandt to his mayoral European colleagues, numerous personalities intervened on his behalf in dealing with the Turkish military junta. These interventions no doubt saved his life, but they did not prevent the Turkish regime, which had decided to break and humiliate him, from inflicting the worst kinds of tortures or from sentencing him to thirty-two years and eight months in prison, accompanied by ad vitam deprivation of political rights. Respect for the adversary and for his dignity is not part of the Turkish state tradition, founded essentially on despotism and on crushing and humiliating of the weak.

It was against this background of state terror and humiliation that the guerrillas of the PKK emerged in August 1984. Launched by fewer than fifty poorly armed youths, the PKK rapidly attracted hundreds and then thousands of young Kurds, who were convinced that the Turkish state would acknowledge the Kurdish national phenomenon only if forced to do so with weapons. It is not superfluous to remember that most of the commanders and leaders of this guerrilla group had been inmates of the Diyarbakir prison and that a number of the combatants had children or other kin of Kurdish prisoners ground down by the repressive Turkish machine.

The shifting of the Kurdish struggle from political to military confrontation, in fact, gave the Turkish army the rare opportunity to regain its prestige and posture as a defender of the "fatherland in danger" to justify its preeminence in the political life of the country. It provided the army with an excuse to obtain the means for its modernization and, especially, to finally carry out the great nationalist plan of "dispersion and assimilation of the Kurds" through depopulation and devastation of Kurdistan.

The deliberate policy of evacuation of the Kurdish countryside was, furthermore, explicitly recognized by the president of the Turkish Republic. In a letter dated April 1992 and addressed to his then prime minister, Süleyman Demirel, President Özal wrote: "Starting with the most troubled zones, villages and hamlets in the mountainous regions should gradually be evacuated.... Given the tendency of the locals to migrate to the west of the country, it would appear that only two to three million people will inhabit the region in the future. If this migration is not regulated, only the relatively well-off portion of the population will have moved and the poor will have been left behind. Thus the area will turn into a breeding ground for further anarchy."10 The president also recognized, in veiled terms, the severity of the Turkish repression: "One must not forget that due to military measures taken in order to put an end to terrorist activities, the population of the southeast has been subjected to very harsh treatment and that as a result, it feels more and more alienated .... "

But these terrible facts had to be presented to the public under a different light. The Turkish president also recommended to his prime minister that "the scope of our activity in releasing press statements, leaking news, and, if need be, spreading 'disinformation' should be increased." Skillful and effective misinformation convinced a segment of the public that the Turkish state was in essence only defending its territorial integrity against terrorist maneuvers. This public opinion was apparently forgetful of the Kurdish persecutions that had occurred well before the start of even the smallest armed action in Kurdistan.

In the framework of this policy, some 2,685 Kurdish villages were razed 11 and a number of cities and mountain hamlets severely bombarded and depopulated. Forced to leave their land, 5 to 6 million Kurds emigrated to the large Turkish metropolises of the west, where they live mostly in misery and are easy prey for fundamentalist and extremist movements. Kurds lacking the means to leave populate the miserable inner suburbs of Kurdish cities, where the annual per capita income is less than $300, compared to $2,000 for the rest of Turkey. In less than two years, Diyarbakir saw its population triple, increasing to 1.5 million inhabitants. The recent experience of Iraqi Kurdistan was similar; following the destruction of villages by the troops of Saddam Hussein, the uprooted peasants were either interned in camps or driven out toward the large cities of Erbil, Suleimanieh, and Dohouk, whose populations tripled or quadrupled in just a few years. Overwhelmed by the economic cost of a war estimated at an average of $7 to $15 billion a year,12 Turkey does not have the means to plan and organize the massive displacement of the Kurdish population as the late President Ozal wished. The government is happy to force the Kurdish peasants westward, without worrying about the problems of their survival or the impact of the pressure of such a hostile population on the security and economy of the Turkish metropolises.

Paradoxically, this war-led in the name of struggle against PKK terrorism-has reinforced the ranks of this party, which only a decade earlier had been one of many small Kurdish groups leaning toward Marxism. In the well-known cycle of repression-revolt- repression, the PKK and the army mutually reinforce each other, using each other as foils while the Kurdish country is devastated and depopulated, the Kurdish society dismantled in a combat with no way out. Without the PKK and its exactions, the army could not justify its control of the society, and without the terrible military repression in Kurdistan, the PKK would have a hard time surviving and recruiting among the Kurds.

Efforts designed to break this infernal cycle in order to find a peaceful solution to the Kurdish problem collide with the intransigence of the army and the conformist Turkish political class. The political group theoretically the most open to this problem, the Social-Democrat Populist Party (SHP) of Erdal Inönü, expelled six Kurdish deputies from its ranks for having attended, as observers, a conference on Kurdish identity and human rights organized in Paris in October 1989 by the Kurdish Institute and France Libertes Foundation, with delegations from thirty-five countries. This excessive sanction so shocked the Kurdish members of this opposition party that within a few days, more than 20,000 of them gave up their membership, thus provoking the near disappearance of the movement in the Kurdish provinces.

The expelled deputies, quickly joined by others, founded a new political group, called the People's Labor Party (HEP), taking on as its first task the opening up of the Turko-Kurdish dialogue in order to fmd a solution to the "Kurdish question" in a democratic context and within existing borders.

This debate in the middle of the Gulf War crisis first found an echo in the circles closest to President Özal and in certain press organizations. Taking into account the great sympathy of international public opinion toward the Kurds of Iraq, victims of the regime of Saddam Hussein, the Turkish president, breaking a seventy- year-old taboo, decided to receive the Iraqi Kurdish leaders Barzani and Talabani in Ankara. In April 1991, following the uproar brought about by the exodus of Iraqi Kurds, he abolished the law on prohibited languages and decided to grant an amnesty that would result in the liberation of more than 40,000 prisoners, including Mehdi Zana, who was freed in May, after ten years and eight months in prison. But like all Kurdish prisoners convicted of "separatism," he continued to be deprived of his political rights, in conformance with the Turkish wish to systematically remove Kurdish political elites from positions of political leadership.

The legislative elections of October 1991 ushered in a new era of Kurdish politics. In the framework of an electoral alliance with SHP, which was hoping to save its seats in Parliament, the new HEP succeeded in removing all obstacles to legal Kurdish political representation bringing in twenty-four members to Parliament. One was Leyla Zana, elected triumphantly as the representative of Diyarbakir. The wife of Mehdi Zana, she was first Kurdish woman elected as a member of Parliament and the first in the history of the Turkish Republic to dare to announce to the house at the time of her swearing-in a phrase in Kurdish on "the brotherhood of the Turkish and Kurdish peoples." This sacrilegious phrase incited one of the most memorable outcries in parliamentary history. The Turkish political establishment, led by Prime Minister Demirel, cried out that this was a scandal and called for the head of the "impertinent." Sacred "Kurdish Passionaria," Leyla Zana became the favorite target of the media and the Turkish nationalists. Nevertheless, in this period of political opening up, certain parliamentary representatives of the HEP were offered high-level political positions, including the vice-chairmanship of Parliament and the presidency of the Commission on Human Rights.

Hopes for a process of dialogue and of peace appeared all the more well founded because Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel, until then very reticent on the Kurdish question, had just declared in Diyarbakir that "Turkey henceforth recognized its Kurdish reality." This was without a doubt an underestimation of the role of the army, the true guardian of the Kemalist temple, worried about the turn of events. In its turn the PKK, fearing that such a political process might take place without the PKK and thus marginalize it, launched a series of bloody actions designed to remind others that nothing could be accomplished without PKK participation.

The escalation of violence culminated in a massacre of 105 Kurdish civilians by the army at the time of celebration of the Kurdish New Year at Cizre on March 21, 1992, and led the advocates of dialogue to back away from their plan. Beginning in March 1992, the latter became the favorite targets of the Turkish counterguerrilla death squads in Kurdistan, which would henceforth make intensive use of special war and counterinsurgency techniques developed in South America.

In four years more than 4,000 Kurdish democrats, including the seasoned writer Musa Anter; the parliamentary representative from Mardin, Mehmet Sincar; and numerous journalists, teachers, doctors, and lawyers were thus assassinated by "unidentified killers," to quote the official terminology. Eighty-eight national and regional directors of the HEP and its successor, the Democratic Party (DEP), were among the victims of this planned massacre of the Kurdish elite.

In March 1993 President Özal, at the behest of the Kurdish elected members, made a new attempt to stop the bloodbath and to explore the possibilities of a political settlement to the Kurdish question, even in the federative context. He asked the Kurdish Iraqi leader Jalal Talabani to negotiate a cease-fire with the head of the PKK. The population, weary from the endless, ruinously expensive, and absurd war, met this overture with relief.

After returning from a trip to central Asia, Turgut Özal died suddenly, just as he was preparing to announce a series of measures for the gradual resolution of the Kurdish problem. His death, officially due to cardiac arrest, remains a mystery to this day, as the autopsy report has never been made public. A few weeks later the principal partisans in the army and in the MIT, including the chief of gendarmerie forces (JITEM), General Esref Bitlis, disappeared under equally mysterious circumstances. Most certainly the army hard-liners had gained the upper hand. After having eliminated their civilian and military adversaries, they embarked on a "total war" to eliminate any possibility of political solution or dialogue.

The election of Süleyman Demirel to the presidency of the Republic was of no great concern to them. Overthrown in 1971 and 1980 by military coups, Demirel knew perfectly well how to get on with the army. The very ambitious but malleable and docile Tansu Çiller, a woman projecting a more modem Turkey to foreign opinion, was named prime minister. Summoned to the army staff headquarters, newspaper editors received strict and detailed orders on the treatment of "events in the southeast" and a list of terms to be used. For the sake of "national consensus," the same circumscription was expected of the political class. The only party in Parliament that risked breaking with the consensus was the HEP, which was banned on July 15, 1993, by a constitutional court whose principal judges were mindful that they had been appointed by the military regime.

The cycle is completed without the army's having to take power directly. The army has only to quiet the last witnesses of the Kurdish drama who have not yet fallen under the bullets of the death squad. In particular, these witnesses are the parliamentary representatives of the DEP, a few Turkish and Kurdish writers and journalists, and personalities such as Mehdi Zana, who, notwithstanding threats, travel the world to give voice to the cries of their oppressed people and to call for the help of apathetic Western democracies.

After an intense media campaign and a series of attacks against DEP offices, the Turkish authorities finally decided on March 2, 1994, to drop the parliamentary immunity of six Kurdish representatives and to incarcerate them. Four of them, including Leyla Zana, had just returned from an informational tour of Europe, during which they had been received by French President Mitterrand and by Jacques Delors, head of the European Union. On June 16 the DEP was banned by the constitutional court because of the "separatist remarks of its president." The thirteen remaining members in Parliament were stripped of their parliamentary immunity and were prosecuted by the State Security Court of Ankara for separatist activities. The prosecutor general requested the death penalty in light of article 125 of the Turkish penal code. As for Mehdi Zana, a sort of barometer of the Turkish political climate of recent years, he was sentenced in absentia to four years in prison for his testimony before the European Parliament and on May 12, 1994, was imprisoned in Ankara. 13

The trial of the Kurdish members of Parliament aroused a sharp reaction in European public opinion. The European Parliament, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, and several national parliaments passed resolutions demanding the Kurds' release. French President François Mitterrand wrote to his Turkish counterpart. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl had a long telephone conversation with "his friend" Demirel to tell him that the German public did not understand how one could arrest and put on trial elected representatives for "crimes of opinion" and to ask him to use his influence to secure their early release. Similarly, several European governments approached the Turkish authorities. An appeal signed by about a dozen Nobel Peace Prize winners was submitted to the United Nations General Secretary in New York by Mrs. Danielle Mitterrand, B. Williams, and me. Mr. Butros Ghali forwarded the appeal to the Turkish government and offered UN's good offices, but Ankara rejected all mediation.

Leyla Zana's Op Ed piece, "In Prison for Being a Kurd," published in the December 5, 1994, issue of the Washington Post, aroused emotion in the U.S. Congress. As a result, the State Department's spokesman urged Turkey to exercise moderation.

Finally, on December 8, 1994, following a drumhead trial of five summary hearings, the Ankara State Security Court sentenced five Kurdish members of Parliament, including Leyla Zana, to fifteen years in prison; one member to seven and one half years; and two others to three and one-half years. About 100 Western observers who attended the Ankara trial unanimously denounced this "parody of justice," some describing it as kafkaesque and others comparing it with the Spanish Inquisition and the Moscow trials of Stalin era. Widespread international media coverage described the verdict as "shameful," "scandalous," and "mediaeval" The European Parliament reacted by freezing its relations with the Turkish Parliament and awarding Leyla Zana the prestigious Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Spirit. Parliamentary members from several countries nominated Leyla Zana for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995. But, despite all the international mobilization, the Turkish Court of Appeals was not deterred from confirming the fifteen-year prison sentence for the first Kurdish woman member of Parliament and her colleagues in October 1995.

Stripped naked, the Turkish judiciary machine, which in the case of the Kurdish MPs had shown itself to be merely a tool for executing the orders of the army and had lost all credibility, imperturbably carries on its zealous work, even in Ankara and Istanbul, cities that usually are the regime's show windows. Here, hundreds of critical journalists, Turkish and Kurdish intellectuals, and supporters of a dialogue and of peace are being arrested, sentenced, and jailed on a variety of pretexts for "criminal opinions."

In the Kurdish provinces trials are now considered an unnecessary luxury; men and women who are a nuisance to the regime or are suspected of "dissidence" or of "separatism" are simply carried off, tortured, and assassinated by one or another of the many gangs and squads of Turkish paramilitary forces. In this "legal no-man's land," described by the New York Times as "Kurdish Killing Fields," the victims appear on the files as "disappeared," victims of "mysterious murders," and the all-inclusive heading of "terrorists killed in the course of clashes." No enquiries-police, legal, or parliamentary-will ever disturb the perpetrators, since, in the Kurdish region under State of Emergency, the army, the police, and the paramilitary forces have unlimited freedom and total immunity. They can murder, loot, destroy, rape, or torture in the most atrocious and sadistic manner; bomb the forests; bum the crops; and machine-gun defenseless civilians from helicopters. According to a soldier's testimony published in an opposition press, the commanders of some Turkish units have instituted a system of bonuses to their troops in proportion to the number of severed Kurdish heads or pairs of ears they bring back. The British weekly The European, in its January 11, 1996, issue, published three photographs "amongst the least shocking of those it had received" in which Turkish soldiers are holding the severed heads of Kurdish men as trophies. The photos had been sent to The European by a member of the Turkish commandos operating in the Hakkari mountains.

Despite the strict control of the press by the Media Office of he Armed Forces General Staff and despite the blackout imposed n the Kurdish regions, preventing observers and journalists from moving around freely and collecting information, news filters trough. How, indeed, could it be otherwise with mobile telephones, ax machines, and the Internet? Moreover, about one million Kurds live in Western countries and act, through a multitude f societies and organizations, to increase public awareness of the tragedy of their people. The Kurdish problem is no longer a matter that concerns only Turkey and its neighbors, such as Iran, Iraq and Syria. It also concerns Western Europe insofar as it raises serious dangers to public order and stability in several European countries, particularly Germany.

Governments that, for strategic or commercial considerations, have long shown considerable indulgence to Ankara, now have more and more difficulty in justifying those positions to their own populations. The Turkish leaders have not kept their often-repeated promises of democratization. No doubt the amendment of article 8 of the so-called Anti-Terrorist Act, passed on the eve of the European Parliament's vote on admitting Turkey to the Customs Union in November 1995, resulted in the release of about 100 political prisoners, including Mehdi Zana. But Turkish law has nineteen other liberty-killing measures available, and the Turkish prisons have since been refilled with intellectuals and journalists guilty of having ideas of their own. Thus the Turkish sociologist Ismail Besikçi, who has already spent more than fifteen years of his life in jail for his writings, has been sentenced to more than two centuries of imprisonment. Sixty-seven of those years have already been confirmed by the Court of Appeals. Mr. Zana, now living in exile in Europe, has been sentenced to another four and one-half years in jail for publishing his two books. Mrs. Çiller who during the December 1995 general elections presented herself as the bastion of moderation against the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, therefore enjoyed considerable Western support. Then in June 1996 she formed a coalition government with the Islamic party, thus completely discrediting herself in the eyes of her Western supporters, who for a while regarded her as a modem alternative to a Turkish political class characterized by corruption and intellectual bankruptcy.

Accused of corruption in a number of scandals, Mrs. Çiller has even been implicated by the German courts of having "close relations with the Turkish mafia." The reason is that a road accident on November 6, 1996, near Susurluk on the Izmir-Istanbul road, had publicly revealed the huge scale of the mutual interpenetration of police, the drug-smuggling mafia, part of the state machine, and the Turkish political class. Many witnesses gave evidence before the Parliamentary Enquiry Commission set up to investigate the scandal. Among them was Hanefi Avci, a senior officer of the Istanbul police, who described the 1992 setting up of an "extra-judiciary organization within the State for fighting terrorism with its own weapons." This organization, which had extensions in the gendarmerie, the MIT, the army, and the National Police Directorate, put into operation a plan approved "at very high level" (that is, by the National Security Council, the MGK, dominated by the generals). In accordance with this plan, a number of Kurdish intellectuals and businessmen, suspected of supporting the PKK, were assassinated. Mehmet Agar, Minister of the Interior, indicated as the head of this organization, was forced to resign, even while boasting about having carried out "a thousand secret operations for the country's safety." In his testimony before the Parliamentary Commission, Mr. Agar contended that all he had done was with the agreement of the MGK. The extent of the scandal was thus understood, and since Parliament dared not tackle the MGK or the army, the commission concluded its so-called enquiry by calling for the lifting of parliamentary immunity from Mehmet Agar and one of his accomplices, S. Bucak, a Member of Parliament of Mrs. Çiller's party and head of a progovemment private militia. This call was never followed up. In his evidence before the commission, Avci had also indicated that, to finance its operations, this "extra-judiciary organization" had taken over the organization of the narcotics-smuggling business. Drug trafficking earns Turkey $25 billion a year-a sum that seems to have increased rapidly, since the Turkish daily Hürryiet, in its June 5, 1997, edition, indicated that the heroin traffic now earned Turkey $ 37 billion. The principal godfathers of the trade, such as H. Baybasin, gave interviews in December 1996 to German, Turkish, and Dutch television confirming that, from the start, they had worked in close collaboration with the Turkish police, army, and political authorities and backed up their assertions with photos showing them in the company of high-ranking Turkish public figures. The British Under Secretary of State for Home Affairs, noting that "80 percent of the heroin sold in Europe comes from Turkey," that "several notorious drug dealers have been found to hold diplomatic passports," and that "several operations against the Turkish mafia have failed because they had been tipped off by the Turkish police," expressed his conviction that "such large-scale smuggling could never take place without the protection and collaboration of the Turkish State."

Bogged down in a bloody war in Kurdistan that it is financing, at least in part, by drug trafficking, Turkey is going through the greatest economic, social, and political crisis in its history. Its political system has broken down; its political caste, lacking in breadth of vision, is disunited and in disarray. Multiplying its warnings about the Islamists, the army is again proclaiming itself the guardian of the Republic and ultimate master of all power. The army bans any initiative, any ideas about a settlement of the Kurdish problem. The Turkish regime is locking itself into a purely military approach.

Yet the generals know that there is no military solution to the Kurdish question, since, despite the massacres and deportations perpetrated over the last seventy years, the Kurdish population has not ceased increasing. The National Security Council, in a recent report, parts of which were published in the Turkish daily Milliyet on December 18, 1996, states that "because of the high birth rate in the Kurdish regions and of the vitality of Kurdish nationalism both inside and outside the country, a change in population balance could, in the long term, constitute a danger.

Research indicates that by the year 2010 the Kurdish population could make up 40 percent of the total population of Turkey and that by 2025 it would have passed the critical 50 percent level. With such a growth rate Kurdish nationalism would come to the fore and its reflection in the number of Members of Parliament could, in the future, have serious consequences."

Population growth, geography, and history all argue in favor of the search for a political solution that would allow Kurds and Turks to live together within a democracy that would respect the rights and identity of each people. Nonetheless, Turkey is a state that, despite its international commitments, continues to victimize its Kurdish population in the name of an obsolete ideoiogy or nationalist extremism.

With the war raging in Kurdistan, Turkey has been driven into the most serious economic, social, and moral crisis of its history. The Turkish regime has entered a new era of ideological glaciation, confronting its 15 million Kurdish citizens with a terrible choice: forced assimilation, that is, renouncing their identity; revolt; prison; or exile. Once again the official voices have been asserting that there is no Kurdish problem in Turkey but rather one of terrorism, fomented abroad. Parliamentary representative Coskun Kirca, a self-proclaimed interpreter of this new atmosphere, declared in plain language, on March 3, 1994, at a House hearing, to applause from his peers: "The Kurds only have a single right in this country: that of being quiet." A proconsul Turk with discretionary powers, called "superprefect of the region in state of emergency," made silence rule in a Kurdistan muzzled and practically off-limits to the foreign press. The Kurdish land has thus lived forty-eight of its last seventy-one years under special regimes, states of siege, and martial law-a sort of no-law zone left to the goodwill of the Turkish generals. All this is happening in a state that is a member of NATO and the Council of Europe, a close ally of the United States, associated with the European Union, a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights and to the Charter of Paris, which is supposed to guarantee freedom of opinion and of association, as well as the right of minorities to preserve their identity. That state tortures its Kurdish population with the financial, political, and military aid of Western democracies, indifferent to public opinion. Mehdi Zana's book is an outcry-his own outcry and that of his tortured people. Will it break the wall of silence surrounding the Kurdish tragedy in Turkey and shake our consciousness on the abominable practices of our "Turkish friends and allies"?

Kendal Nezan

Paris, June 20, 1997

|