| Foreword

While the Medes and the Persians are familiar in the Western world, there are few who connect the Medes with the fighting that has been going on in northern Iraq in recent years. Yet the Medes are the ancestors of the Kurds who beginning in 1961 were pitted in battle against the Baghdad government and more than held their own.

The leader of the Kurds is Mustafa Barzani, whom I know as a friend. The history of the Kurds, which Dana Adams Schmidt unfolds in this volume, is history I have heard from the lips of Barzani. I have heard it also from Kurds in northern Iran and eastern Turkey and from furtive Kurdish visitors to my office, who arrive in this country as persecuted refugees.

The details of this pre-1961 history vary, narrator by narrator. But the essentials, as I have heard them, are accurately stated by Schmidt. Barzani in the 1940's was adjudged an interloper by the Iraqi government, guilty of something close to treason because he served as mediator between two quarreling Kurdish tribes. Iraqi intelligence in those days saw conspiratorial implications in mediation; and Barzani left the country for Iran - with thirty-five thousand men, women, and children, according to Schmidt, with fifty thousand as Barzani told me. In Iran he joined the Mehabad government, which had been carved out of northern Iran from territory the Russians occupied during World War II. Qazi Mohamed, a mullah, was head of that government and he lies in an un-unmarked grave in the bleak cemetery at Mehabad, having been hung by the Teheran government. He is often called a Communist; but, while I did not know him, I always doubted the charge, for though he was supported by the Soviets, his program did not have the telltale signs of a Communist regime. Moreover, I knew some men associated with him and they were Kurdish nationalists, not Communists. One was the Secretary of War, Amir Khan Sharifi - the grand old man of Kurdistan who died in 1959. The other was his lieutenant, Barzani.

When the Persian army moved north against Mehabad, Barzani retreated with his cavalry of a thousand Kurds, engaging in skirmishes. He returned to northern Iraq and was invited back to Baghdad. But he declined, he told me, for fear of being hung; and he probably acted wisely, for some of his associates who returned were hung. Barzani asked instead to go to Russia - his only real choice because he had no other, Iran and Turkey not being friendly to him. The Russians at first turned him down, revealing a schizophrenic attitude toward the Kurds that appears over and again in their history. Then they changed their mind.

Barzani told me he took one thousand Kurds with him into Russia, but the number may have been the more modest one given by Mr. Schmidt. He stayed in Russia about twelve years, being well treated as a refugee. While many Kurds who went to Russia with Barzani married Russian women, Barzani, whose wife and children were in Iraq, did not.

When Kassem took over Baghdad in 1958, Barzani returned to Iraq; and it was there I came to know him. On our first meeting I said:

"I understand you are a Communist."

He was instantly on his feet, shouting, "Show me your proof! Show me your proof!"

"You were guest of the Russians for a dozen years," I teasingly replied.

"To save my neck," he retorted; and then, sensing that I was not wholly serious, he relaxed.

This rude beginning was the start of a warm friendship, and I discovered in Barzani the smouldering coals of nationalism and independence familiar to every American who remembers 1776.

After listening for a whole afternoon to the accumulated grievances of the Kurds that came gushing from Barzani, I saw Kassem and brought up with him the question of this troublesome minority that today is scattered in Turkey, Russia, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. I was in no sense a go-between. I was only concerned with the Kurds as people. I had seen so much of them in the Middle East that I felt I was on an understanding basis with them.

My respect for the Kurds had started with my acquaintance with the porters in Beirut, most of whom are Kurds. They carry incredible loads on their backs, as they do in Tabriz. In Damascus I came to know about Saladin, the Kurdish leader of the Arab armies who retook Jerusalem from us Christians. When we took Jerusalem, we beheaded thousands merely because they were "infidels." When Saladin captured it he proved, I thought, to be more Christian than the Christians, for he beheaded no one. And so Saladin became a hero and his tomb a place of pilgrimage. In Turkey I learned that it was a crime to speak the Kurdish language or to publish anything in the Kurdish alphabet; and I found the Kurds pretty well segregated and confined in the eastern area. In Iran a few Kurds reached positions of eminence in government. But in northern Iran the Kurds were so suspect they seldom could get a government job, no matter how lowly. I had heard of similar discriminations against Kurds in Iraq and asked Kassem about it.

He replied, supporting the Kurdish cause. He told me that when he came to power the law lay heavier on the Kurd than on the Arab. "If a Kurd and an Arab robbed a bank," he said, "the Kurd was hung and the Arab was sent to jail." Kassem, I learned, was correct; for the laws promulgated by the British, when they held Iraq under a mandate from the League of Nations, often discriminated against tribal people, whom every ruler found to be troublesome. Kassem annulled those laws and spoke to me in terms of Kurdish equality within the Iraqi commonwealth.

Whether Kassem changed his mind or whether his avowed policy was thwarted by the bureaucracy, I do not know. I suspect it was the latter, for the currents of hate, suspicion, and vengeance run deep in that part of the world.

My Baghdad talks with Barzani left no ground for thinking he wanted a Kurdish state. He pleaded then, as now, for autonomy; and by autonomy he meant in general what we call statehood within a federal system. Kurdish language, Kurdish history, Kurdish poetry - these are precious to Barzani. And to preserve them, laws and regimes favorable to Kurdish culture are necessary. So it is that within Iraq the Kurds launched a political party of which Barzani was titular head. This party was legal, active, aggressive, and non-Communist under the first years of the Kassem regime.

There doubtless are Kurds who are Communists. A Syrian Kurd, who now is a refugee in Russia, is said to head the Syrian Communist Party. That may be true. But the Kurds are more knowledgeable about Soviet Communism than most of us. They know that within Russia, Kurdish nationalism, like the nationalism of Turks, Persians, Uzbeks, and Kazakhs, has been severely curbed. They know the inexorable consequences of Russianization. Yet to some who live in the vortex of the Middle East, Russia is a refuge now, as it has been for centuries. The aspirations of minorities, however, do not flourish in the Soviet scheme any better than they do in Turkey, Iraq, or Iran. They probably suffer more in Russia because Communist cadres are extremely efficient and ruthless in their control and regimentation. Kurdish nationalism may in time receive Soviet sponsorship. But if that comes to pass, Kurdish autonomy will have entered a dangerous stage.

The hopes of the Kurds lie in Barzani's formula - statehood within one or more non-Communist countries. The case for it is firmly established; and this volume gives a vivid account of the forces behind it. The book serves the high function of baring the Kurdish soul to America for the first time. Never before have Kurds been able to reach through to American consciousness. This time I hope they succeed. They will succeed, if Americans who read this journal relate it to Brandywine, Yorktown, and Valley Forge.

William O. Douglas

January 18, 1964

With a Foreword by

Justice William O. Douglas

"For me these forty-six days with my Kurdish friends had been a high point in twenty-five years of newspaper work." Thus Dana Adams Schmidt, New York Times correspondent in the Middle East, describes his recent adventure into Iraqi Kurdistan to interview the guerrillas struggling to win national recognition from the Iraqi government.

Schmidt's trip had to be kept secret (indeed he never reveals just how he did get in and out of Kurdistan) ; to all appearances he just disappeared from his office in Beirut. He traveled on foot, by mute, when particularly lucky by horse and on two occasions by jeep. Much of the traveling was done at night with the days spent in hiding. The physical dangers were acute; they were strafed more than once by the Iraqi air force. Always his escort was careful to keep the identity of this 6'3" "stranger" from the villagers, for fear that Kassem's men would discover his presence.

The climax of his trip was an interval of some ten days spent with Mullah Mustafa Barzani, the leader of the Kurdish rebellion and the man most loved and feared in Kurdistan. Barzani invited the Western press to his headquarters so that the Kurdish cause - that of a strong-willed people, anxious for their measure of political self-determination - would be known to the world.

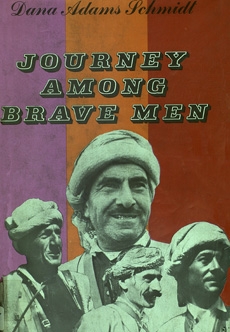

Interwoven with Schmidt's own personal narrative is the story of the Kurds; of the limited resources of their pathetic army; of their love of folklore and their strange, bitter legends; of a history of continual domination by one national group or another. For this account Dana Adams Schmidt draws on his own rich understanding of the contemporary political scene in the Middle East, as well as on studies of Kurdish history. Included is an excellent collection of photographs showing the Kurds in their mountain hideouts, and a first-rate map.

For this assignment Dana Adams Schmidt received the George Polk Award of the Overseas Press Club - "For the best reporting requiring exceptional courage and enterprise abroad."

Jacket design by Edith Allard

|