| Éditeur : Blue Crane Books | Date & Lieu : 1999, Cambridge |

| Préface : | | Pages : 116 |

| Traduction : | ISBN : 1-886434-80-5 |

| Langue : Anglais | Format : 150x230 mm |

| Code FIKP : Liv. Ang. 4351 | Thème : Politique |

|

Présentation

|

Table des Matières | Introduction | Identité | ||

Versions

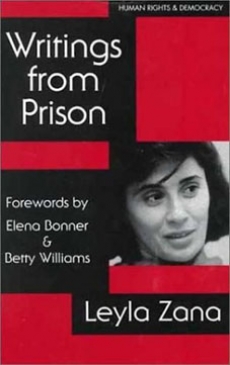

Writings from Prison Layla Zana | |||||

| Foreword I think a book about a remarkable woman by the name of Leyla Zana needs no introduction. The life reflected on these pages speaks volumes and certainly a lot more than can be said by an author of any Foreword, however superlative. Indeed, Leyla Zana can truly be called a daughter of the Kurdish people, to whose rights she has devoted her life. She can also rightfully be called a self-made woman. Leyla Zana was born in 1961, in a small Kurdish village. As a teenager, she was married to a man many years her senior who was actively involved in the Kurdish movement for national liberation and who introduced her to political activity. She was fifteen when she gave birth to a son, and soon after she became the first young woman in her town to be awarded a high school equivalency diploma. When Leyla was twenty, her husband, then the mayor of the town of Diyarbakir, was arrested and sentenced to thirty-years' imprisonment. At the time, Leyla was pregnant, and soon their daughter was born. A young mother with two small children destined to grow up fatherless, she continued her education, worked to create women's groups in Diyarbakir and Istanbul, and wrote for a newspaper. In 1991 Leyla Zana became the first Kurdish woman to be elected to the Turkish Parliament, where she was one of the rep resentatives of the sixteen million Turkish Kurds and worked to protect their rights. One has to keep in mind that for the Turkish Government no means are too low for the persecution of the Kurdish people, from bombarding Kurdish settlements and a scorched-land policy to prohibiting the use of their mother tongue. In March 1994, Ms. Zana, together with three other Kurdish MPs, was stripped of their Parliamentary immunity, arrested, and, in December of that year, sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment. Her children were now left to the care of relatives and friends, while their mother became a symbol of the struggle against the genocide of the Kurdish people. Her uncompromising stand for human rights earned her the recognition of various international organizations, and she received many awards. Among them was the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought awarded to Leyla Zana in 1996 by the European Parliament. While writing the nomination of Leyla for that prize, I kept thinking of the high price in freedom and even life paid by those who devote themselves to the struggle for human rights. In the fall of 1997, I, too, was thinking of Leyla's plight, of the plight of her husband and children, and of their entire family. Together with my son's family, I was on my way to the lawn near the U.S. Capitol to greet a group of Kurdish activists and Kathryn Porter, the wife of U.S. Representative John Porter, who were holding a hunger strike to demand freedom for Leyla Zana. They stayed outside all day, spending the night in a nearby church. The day was gray and blustery cold, with a strong gusty wind, the kind that chills to the bone. We shook the hands of the fasting people. Their hands were very cold and their faces had a bluish hue. I realized that while no words of ours could warm them up, they were being kept warm, despite the cold hands and pale faces, by the hope that their voices would be heard. This collective hunger strike lasted quite a while, and I wrote about it to the First Lady: Dear Mrs. Clinton, I know the nature of a hunger strike, not from novels but from personal experience. Twenty-nine days is a long time; such a strike threatens not only the health, but also the very life of the hunger strikers. Kathryn Cameron Porter is among them. She is the wife of Congressman John Porter, and I understand you know her personally. On 17 November the hunger strike was moved from the Capitol to the square in front of the White House. It is so close to your residence that your assistants can easily walk to the site and get all details about the case of Leyla Zana, this young woman who is a mother of two children and also is an elected member of the Turkish Parliament. I will not recount her case here., but I implore you to show compassion and understanding and to use your moral authority to help those who are striving for the release of Leyla Zana. With respect and hope, I received no response to this letter. After a Congressional resolution in support of the demands of the hunger strike, it ended. However, today, a year and a half years later, Leyla Zana is still imprisoned. In May 1994, on her daughter's birthday, Leyla wrote her daughter, Ruken: "I would so much like to be with you today, on your birthday. But don't worry, we have a long life before us. We will have many birthdays to celebrate together. I wish you a happy birthday and send you many hugs and kisses, my heart." How many more years must pass before the entire Zana family celebrates a birthday together? I hope that the reader of this book will think of what he or she can do personally to hasten the day of freedom for Leyla Zana. Elena Bonner,

Foreword by Betty Williams In a world filled with ills and conflict—When was it ever not I thus?—there are always people who stand up and speak for the simple rights of all human beings simply to exist. Leyla Zana is such a person. Her courage shines like a beacon of compassion and understanding. And we can all be grateful that, today, we have the technology and the communicative ability to share in her story. Throughout the past twenty-three years I have dedicated myself to the hard work of peace, and especially to working for the rights of women and children. It is a much misunderstood word—peace. But in every language it means not just the absence of violence and denial of basic human rights, but the simple right to exist without conflict, to be allowed, under whatever one believes his or her Supreme Being to be, to love and be loved, to hold true to the belief that all human beings-indeed, all creation—deserve justice and compassion, and that we are all one human family. In recent months the world has witnessed the coming of peace to my homeland—Northern Ireland. But few remember that it was the women of Northern Ireland—the wives, mothers and daughters of Northern Ireland—who stood and raised their voices against the senseless cycle of useless violence we saw in our streets and across the beautiful green land of our birth. That voice, raised in courage and determination, announced a gentle but firm commitment to change, to doing things differently, to exposing the insanity of war and all forms of violence. It could not be silenced then, and it will never be silenced so long as there are women of courage—women like Leyla Zana—who will stand and demand that their voice be heard. We must all have the courage—men and women alike—to listen when such a voice is raised. But more important, we must have the courage to act, to work together as a human family to ensure that such a voice is not silened, shall never be silenced. Certainly, no human being should be incarcerated for his or her political beliefs. Some of us will be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for raising our voices. But those millions of others who raise their voices and are not recognized—who may never even be known outside their small area of influence—must continue against all odds, against all traditions, against all forms of insanity that would crush them and see them silenced forever. Leyla, we honor your brothers and sisters who in defending justice have already paid the ultimate price with their lives, for they used the technique of nonviolence, which is truly the weapon of the strong. God bless you, Leyla Zana; you will always be in my prayers. Betty Williams | ||||