|

INTRODUCTION

E.LDoctorow

Whatever [the writer] beholds or experiences comes to him as a model and sits for its picture.... He believes that all that can be thought can be written. ... In his eyes a man is the faculty of reporting and the universe is the possibility of being reported.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson,

GOETHE; OR, THE WRITER

Some of us who are writers find the universe in our marriages and affairs, in the inadequacies of our parents, and the antagonism of our peers. We produce heroes and heroines of private life. What is possible to report is the exquisite sensibility we have for the moral failings of those around us. This is not necessarily a misuse of the faculty, but neither is it the only use. There is a kind of writer appearing with greater and greater frequency among us who witnesses the crimes of his own government against himself and his countrymen. He chooses to explore the intimate subject of a human being's relationship to the state. His is the universe of the imprisoned, the tortured, the disfigured, and the doleful authority for the truth of his work is usually-his own body. Thus we have Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago, an account of the vast Soviet system of secret police end labor camps. And because it is set in a part of the world to which we have tenuous connection, we can be safely righteous about the prisoners freezing and dying there. What can we do for them short of beginning World War III on their behalf? Hope that through the weird, stiff maneuvers of international diplomacy—treaty signings and commodity sales and cultural exchanges—some relaxation, some loosening of the seized soul, some ease, will come to the murderously rigid Soviet state paranoia.

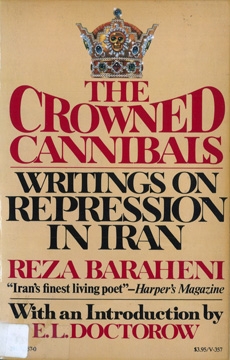

Yet we have living among us, in exile, another of the writer-witnesses, and his name is Reza Baraheni. His country is Iran, and TuTis chronicler of his "nation's torture industry and poet of his nation's secret police force. In this case our aesthetic response must be a shade less righteous because Iran, by all responsible accounts, is a country whose ruler we installed ourselves and to whose health and well-being we have been devoted in all the usual ways –with our planes and tanks and computers. "Azudi has shattered the mouths of twenty poets today," says Reza Baraheni, speaking in a poem of one of the Shah's torturers. And how do we, who as aestheticians know that politics makes bad art, judge a line like this? And which of our critics who believe that words are a tapestry, and of no value except in the pretty designs they make, can deal for art's sake with the embarrassing, unobjectified, uncorrelated bitterness of a writer whose spine has been burned with an acetylene torch? What do our literature teachers say who do not grant art a political character but who would speak to their students of The Human Condition? For Baraheni or Solzhenitsyn or Gloria Alarcon in Chile or Pramoedya Ananta Tur in Indonesia or Kim Chi-Ha in South Korea, it turns out that The Human Condition is first of all to be made of flesh that can be tom, organs that can be violated, bones that can be fractured. In America it is or should be every writer's dream to give literature back to life. The writer-witness of state assaults on human beings in the twentieth century has the corollary problem: How to communicate to those who insulate themselves in literature, the terrible inadequacy of aesthetic criteria as applied to human suffering. A problem of craft: How does the novelist, as he describes a scene of torture, keep us from closing the book—or from making patronizing distinctions between what is aesthetically successful and what is only sensational?

Reza Baraheni is not unacquainted with the demands of high criticism. He received his Ph.D. in English literature from the University of Istanbul, Turkey, in 1960. His dissertation was a comparative study of Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, Swinburne and Edward FitzGerald. Before his arrest in Iran he was a professor of English and Dean of Students at the University of Teheran. He is a novelist, a poet, a translator of Shakespeare, T. S. Eliot, Pound, E. E. Cummings, Camus, and is considered by many of his colleagues in Iran to be the virtual founder of modern literary criticism in that country.

Somehow, in the inverted logic of tyrannies, achievements such as these threaten the state. And so it came to pass that Baraheni was imprisoned and tortured for one hundred and two days in 1973, before public opinion, generated by Amnesty International, the American PEN and the Committee for Artistic end Intellectual Freedom in Iran, secured his release and his exile to the United States. Baraheni emerged with a new credential—he'd become one of the writer-witnesses. And in a poem called "Our Mission in Arras," in reference to the river between Iran and the Soviet Union where dissidents of both countries are rumored to have been drowned, he writes:

A dissident poet from Russia whispers to me

I whisper back

We smile. We depart

Soft pieces of ice pass between us …

So let us propose discussion of the idea that a new art with its own rules, is being generated in the twentieth century: the Lieder of victims of the state It sings of regimes so repressive as to be fun-house mirror images of civilization. It recounts years of solitary confinement. It tells of pliers for pulling fingernails, it speaks of electric currents sent into sexual organs, it describes prison cells in which a person can neither stand up nor lie down. True, this is a necessarily small range of subject. There is a limit to the possibilities of metaphor. The subtext always has to do with the degrees of death in life. But within these strictures the poet is entitled to sing with his or her own voice.

One feels a certain amount of curiosity—let's call it that—for the individual who gives his life and loyalty to secret police organizations, but especially for the trolls in that netherworld who do the actual raping, breaking and maiming of poets. From all reports they look like ordinary human beings. One presumes, therefore, that in order to do what they do they perform an act of excommunication, so that the victim of the abuse cannot be considered human and the rights of his or her person cannot be thought of as human rights. Hundreds of years ago such emotional preparation for torturing invoked the name of God. In our century it takes the name of Caesar. But quite clearly what is involved, always, is the inability of the torturers to accept their own mortal designation. The knowledge of flesh, of the terrible vulnerability of the flesh, and of the mind, of the fragile psychosocial constructs which support it, is a knowledge too great to be contained. Someone must be punished—mortality, the pride of the brain and the grace of the body, must be driven back into itself. The prisoner, that pretender to life and thought and self-possession, must be taught what a broken, crawling, pleading piece of excrement he really is.

Surely, then, such hate of self, of the very idea of oneself, is the root of the torturer's being. Yet there is a limit to our curiosity, as much as for the common roach of whom we are similarly aware for his ability to adapt and survive. There are others afflicted with self-hate who do not torture—common maniacs at the worst, who rampage and kill and are apprehended and treated by one or another means society has for them. But the torturer is distinguished by being accredited by society. He is that maniac whose inhuman instincts are educed, paid, titled and granted solemn rank with uniform and working hours and pensions for his future. That is what current political analysis must mean by the phrase banality of evil— the appropriation of evil by the state, its incorporation into law, the lifting of the dark spirit of the individual from its own responsibility, leaving it shining with belief and rectitude.

Thus the new poetry can bring to us character as well as event. Of course, a major technical problem is that the torturers all have the same speech, the same rationale usually worked out for them by their superiors (who might themselves be too delicate to witness what they do). It goes this way:

“If you do not torture, you do not find the terrorists. Do you think they would talk if you gave them a cigarette and a cup of tea? We ourselves are family men. We have wives and children at home, and it is not pleasant for us to slice off women's nipples or hang men by their testicles. But you must appreciate our enemies: they are out to bring down civilization as we know it. They would incite the population with lies printed in newspapers (if we allowed newspapers to be published) or with speeches in public places (if we allowed people to gather). They will stop at nothing. And that is why we interrogate in our prisons writers, artists, intellectuals, lawyers, doctors, teachers—or anyone, in fact, who might show signs of thinking like them."

There is not much an artist can do with that like the form of the sonnet, very strict.

Nevertheless, it is always a wonder to see how a government which proposes itself as a means of creating a civilized life for people maintains itself at the expense of the people. This peculiar moebius strip of logic leads us in its twisted way to the thought that in the twentieth century all people are, by definition, the enemies of their own governments. Thus we see today in every part of the world and under every ideology, from the most left or the most right, a citizenry brought to its knees by its protectors.

The organization known as Amnesty International quietly investigates and records cases of political imprisonment and torture around the world. It is one of the newer organizations we have, along with the Wildlife Conservation Fund, Save Our Shores, Ban the Nuke, and so on, that together indicate the wide front of the losing battle human beings are today waging against their own destructiveness. According to Amnesty International, in its report on torture published in 1974, no less than sixty countries of the world were systematically practicing torture on their political prisoners. All, presumably, are members of the United Nations, which in 1966 unanimously adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the right of prisoners not to be tortured.

One can find little justification for the concept of progress and the perfectibility of humankind in such grisly hypocrisy. It is true that slavery in the sense of its widespread practice in the nineteenth century and before is not now an endorsed custom in most recognizable societies. That might be considered progress. But one could make the case without too much difficulty that political imprisonment of a few is the symbolic and pragmatically effective slavery of the whole. Or that just as everything in our century has speeded up—our travel, our means of dispensing information— torture might be a kind of speeded-up slavery, a life of slavery in instant form, condensed for the sake of economic convenience so that the slave victim does not have to be supported for an entire lifetime. Thirty-five or forty years of unendurable labor under abominable conditions can be accelerated by means of modem technology and delivered in a year or less of intolerable pain and debasement.

In our country, of course, we do not commit atrocities upon each other in any systematic national way. There is no federal policy in existence that calls for torture of dissidents or protesters —or indeed, without distinction, the contrasting majority who do not dissent or who are silent. We are a democracy. But if, like me, you live in a quiet house in a pleasant neighborhood where trees grace the yards, I can show you that if Reza Baraheni were to ring your bell, or mine, and recite one of his poems to your astonished face, or mine, he would have come to the right door. You and I might by nature avoid stepping on insects, but the torturers of Iran and of Chile are as close to us as the child is to the parent. They are our being, born from our loins. Look, a terrible connection is made with these dark, exotic faraway places, these barbaric civilizations who do not have our tradition of freedom, of justice: they are ours. We made them with our Agency for International Development and with our Office of Public Safety. We made them with our Drug Enforcement Administration and our Military Assistance Program. With our genius for acronym, we made them.

How worrisome that we who claim democracy for ourselves have to protect it by refusing to extend it to other people. One would think that the idea of partial democracy was a logical impossibility. One could as well speak of being only partly murderous. But the impossible is what we believe—logic that falls apart the instant we try to put it together—when we construe certain kinds of tyrannies in other places to be necessary to what we think of as our freedom.

Perhaps we are not free and the reasoning here is actually consistent. Perhaps there is no freedom anywhere—a kind of domino theory, as it were, the serial connection and collapse beginning with the first imprisonment without trial, and torture, of some obscure foreigner whose thoughts are too dangerous to endure and who is imagined, in his agony, to benefit the state. Perhaps we are not tortured because we are safely docile and cheerfully buy shares in business firms who distribute with the encouragement of our government weapons of containment and devices of technological repression used by the thugs the new poets tell us of.

In Democracy in America, Tocqueville describes what tyranny would be like in a democratic nation. "It would degrade men without tormenting them... it seeks, on the contrary, to keep them in perpetual childhood… the will... is not shattered but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are consistently restrained from actions. Such power does not destroy, but it prevents existence. ... it stupefies people and all the nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of tamed and industrious animals." Perhaps in this, as in so much, the canny old Frenchman is right: If you or I do not condone torture, who among us does? If we abhor gangsters and tyrants and dictators, who among us installs them in their power? Let us have their names, who act in ours.

One reads Baraheni and wonders with a peculiar chill why there is not an ongoing national cry of protest and outrage on behalf of all tortured people everywhere. Why do we not hear from the pastors of our churches, our college presidents, our statesmen? Where are our community spokesmen and our intellectuals and artists, our Nobel prizewinners, our scientists, our economists? Why do we not hear from our businessmen, doctors, lawyers, our labor leaders, our police chiefs? Why is there not some great concerted refusal to condone, assist, endorse or do business with those who practice torture? Surely here is one moral issue which cannot be obscured by language or compromised by political point of view. In the push and pull of diplomacy, the manipulation of public opinion, the granting or withholding of money and of arms, why, with our immense power, can't we put an end to torture—at least in those states, construed as our friends, that are under our influence? Surely the torture of individuals extends beyond the limit of our own barbarism, the hungers of our corporations and our own paranoid sense of security, so that we can safely say: Not this far—at least not this.

Or must we continue to watch, unconnected and stupefied, the rise of a new art form? And shall we wager how long it will be before we produce our own native practitioners? Or must we wonder with Samuel Clemens if the human race is a joke? And if it was devised and patched together in a dull time when there was nothing important to do?

The Crowned Cannibals

Terror in Iran

Iran is a country of stupendous figures. When buying arms, she negotiates in billions; when her army, air force and police are sent for training in the United States, they come in detachments of thousands; when she prepares to step up oil production to meet the requirements of a deficit budget, it is a matter of billions of dollars and millions of barrels; when ships loaded with arms and cargo become jammed in the ports of the Persian Gulf, and trucks carrying food and spare parts from Europe and the Soviet Union line up for weeks on end on the borders of the country, the economic waste is again counted in billions.

Three years ago Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, told the news media in America that he was driving his countrymen to the portals of 'The Great Civilization." One would have thought that he had rational statistics to prove it. Instead, he solved the problem with yet another colossal contrivance of numbers. Back in Iran, he simply changed the Iranian calendar by decree, from the solar Hegira year of 1355 to the year 2535—what he grandiosely declared to be "the Calendar of Cyrus the Great."

Like everything else in Iran, this too was imposed overnight. Now we Iranians live not in a crudely conceived Orwellian utopia of 1984, nor in the dashing odyssey of Stanley Kubrick's 2001, and no less in a crass science-fiction fable haphazardly proposed for, say, 2200. Rather, we have been ordered into the majestic year of 2535(1), concocted, computerized and processed in the wayward imagination of His Imperial Majesty, the Shah of Shahs, Light of …

|