|

PRESENTATION

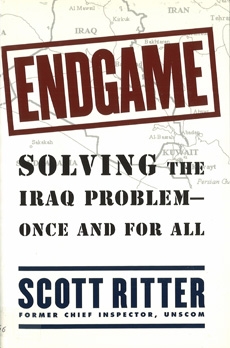

The resignation of Scott Ritter as chief weapons inspector for UNSCOM in August 1998 made front-page news around the world. Now Scott Ritter draws on his seven years' experience hunting Saddam's weapons of mass destruction to take readers inside Iraq and show that country as it has never been seen by outsiders before. In Endgame, he dissects the failure of U.S. policy in Iraq and reveals a bold new approach to ending the ongoing Iraq crisis.

Ritter describes Saddam Hussein's rise to power, painting a damning portrait of a dictator who ruthlessly eliminated rivals as he fought his way to the top. Ritter explains how Saddam cleverly drew on tribal and family connections to consolidate power and then outmaneuver and often execute opponents.

Once he had become the uncontested strongman in Iraq, Saddam began planning the domination of the Persian Gulf region, fighting a war with Iran, threatening Israel, and finally invading Kuwait, the action that provoked the Gulf War. Along the way Saddam repeatedly purged Iraq's military, putting his own key allies and relatives in charge. He also discovered the value of chemical weapons and ballistic missiles, which he used to turn the tide in the war against Iran.

When the U.N. Security Council authorized inspections of Iraq's chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons facilities following the conclusion of the Gulf War, Saddam put in place a concealment program designed to preserve his weapons capabilities. It was this concealment mechanism that UNSCOM spent seven years trying to penetrate in its search for Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. Ritter takes us with him inside some of Iraq's most carefully guarded sites as he describes what it was like to conduct these inspections. He tells stories of dramatic face-offs by unarmed inspectors with hostile Iraqi guards and officials.

Endgame criticizes current U.S. policy toward Iraq, pointing out that we have squandered an international consensus and now find ourselves virtually isolated over our Iraq policy. Scott Ritter offers a way out of the Iraqi morass, proposing a bold and innovative solution to the current crisis. He argues that the U.S. should again take a leadership position on Iraq if we are to avoid facing a rearmed and emboldened Saddam on another battlefield in the future.

Acknowledgments

I would like to give special thanks to my friend and accomplished counselor, Matthew Lifflander, for the sage advice and words of encouragement throughout this project, but especially for the support provided since my resignation from the Special Commission. Matt was a one-man dynamo, providing stellar public relations and legal advice, which was driven by one thing only—Matt’s true concerns for the welfare of a friend. Without his kind and able help and friendship, none of this would have been possible. I also want to thank Matt’s secretary, Helen Guelpa, for her outstanding support throughout this effort, and Matt’s colleagues at Rubin, Baum, Levin, Constant and Friedman, who so patiently tolerated my intrusions on their work space and time.

To my agents, Eugene Winick and Sam Pinkus of McIntosh & Otis, I give thanks for their hard work, gentlemanly manners, friendship, and persistence in bringing this book to fruition.

This book could never have been written without Robert Katz, who brought his considerable experience and precise writer’s eye to sharpen, define, and bring life to this book under very severe deadlines. Bob deserves great credit for taking the efforts of a first-time author and overseeing their transformation into something suitable for publication.

I want to express my appreciation to the staff of Simon & Schuster, who had faith in this project and the perseverance to see it through. I would especially like to thank my editor, Bob Bender, for his vision concerning this book and his sense of humor and wisdom in guiding the project from beginning to end.

This book is very much the story of UNSCOM and Iraq, and I am deeply grateful to Rolf Ekeus, Richard Butler, and Charles Duelfer for giving me the opportunity to serve such a noble cause. Whatever our professional differences may be today, it was an honor and a true pleasure to work for such men. I would be remiss not to express my sincere gratitude to all my former colleagues, especially Nikita Smidovich, Norbert Reinecke, Roger Hill, Gary Crawford, Wayne Goodman, Dianne Seaman, Gabriella Kratz-Wadseck, Cees Wolterbek, Igor Mitrokhin, Steve Black, and Tim McCarthy. To Didier Louis, a fellow traveler, my appreciation for your friendship and services rendered. I also would like to highlight the courageous and brilliant work carried out by my friend Bill McLaughlin in furthering the cause of disarmament in Iraq, and also note that it was Bill who, in a conversation with me on the eve of my resignation, coined the phrase “the illusion of arms control,” an argument so convincing I embraced it as my own.

Avery special thanks goes to the formidable Chris Cobb-Smith, my friend and colleague whose unique blend of professionalism, hard work, and humor made a difficult job under trying circumstances not only efficient, but actually enjoyable.

To those friends and colleagues from around the world who must remain unnamed, but without whose help my work could never have been done, thank you for a service that to this day is still unappreciated by some and unknown by most.

To my mentor and friend David Underwood, and to Bill Eckert, Stu Cohen, and Larry Sanchez, four Americans who had the faith to believe in UNSCOM and my ability to carry out the mission, my deepest gratitude. To Burt, Mick, Darcy, Dave, Stacy, and the others—thanks for your dedication and help for a cause that probably created many difficulties for you, but to which you were unfailingly loyal.

To my best friend, Bob Murphy, and his lovely wife, Amy, and to the entire Albany gang—Mike, Mark, and Becky—thank you for being there when I needed to regain my equilibrium from the rigors of inspection work and writing.

To my parents, Bill and Patricia Ritter, a special recognition for instilling in me the values that have carried me through life, and to my entire family—especially my sisters, Shirley, Suzanne, and Amy, and their families, and my father- and mother-in-law, Bidzina and Lamara Khatiashvili — for their support and encouragement of everything I have done.

And finally, my deepest thanks to my lovely wife, Marina, and my daughters, Victoria and Patricia, who patiently supported me during my service as an inspector—you make life worth living, and every day a wonderful experience.

Author’s Note

The Arab language is a rich language that makes use of subtle phonetic sounds to express different meanings. Although the Arab script renders these subtleties, the Latin alphabet of the English language does not. There are several schools of transliteration of Arabic into English. 1 am not an Arab linguist and have opted usually to defer to Amatzia Baram when transliterating the complex family names set forth in this book. However, for certain names, such as Saddam Hussein (Husayn is Professor Baram’s preference) I have decided to use the common spelling because of its familiarity. Consequently students of the Arab language will note an inconsistency in my rendering of Arab names.

Hastings-on-Hudson, New York

Prologue

UNSCOM 255

August 2, 1998. We were 10,000 feet over the Persian Gulf, headed out of the haze for blue skies and Baghdad. Even then we knew this was our last shot at beating Saddam Hussein at his own game. In the seven years since being pummeled by Desert Storm, he had proved himself to be the master of deceit—playing his sly, winning hand of concealing Iraq's weapons of mass destruction from the world, specifically from UNSCOM, the United Nations Special Commission inspection apparatus, of which I was chief inspector. But now we had an ace up our sleeve, a counter deception all our own that would break the case wide open. It would all hinge on timing and the clock was running.

We’d lifted off from our base in Bahrain in UNSCOM’s leased L-100. The white, lumbering aircraft was a civilian variant of the cavernous C-l 30 and there were only three of us in the flight cabin, sitting on a bench just behind the cockpit crew. I was briefing my boss, UNSCOM’s executive chairman, Richard Butler, who was en route to Iraq with his deputy, Charles Duelfer, for routine talks with the Baghdad government. Officially, I was in Butler’s party, which included an entourage of about twenty disarmament experts in the rear cabin, to provide technical assistance and advice during the course of his visit. But my real purpose, as chief inspector, was to command a series of surprise inspections—an operation we called UNSCOM 255—so called because it was UNSCOM’s 255th inspection since its inception. We were set to begin as soon as Butler’s visit ended on the 5th and he was out of Iraq. I had forty-two men on the ground in Bahrain and Baghdad ready to move in, awaiting Butler’s green light.

The four inspection sites we were ready to pounce on were all exceptionally promising but one was a real gem, chosen on the basis of one of the hottest intelligence tips we’d ever scored: the precise location of a cache of ballistic missile guidance and control components, enough to equip a dozen missiles —the hardware and the heart of Iraq’s chemical, biological, and nuclear deliver)' potential.

Under the 1991 Security Council resolution providing for Saddam’s disarmament, Iraq was permitted to retain ballistic missiles with a range under 150 kilometers. Suspicion arose from the very start however that Iraq would seek to maintain a covert long-range missile capability.

It had agreed to declare its inventory of long-range missiles and associated production capabilities. UNSCOM’s job was to destroy this inventory. Within months of that declaration, it became clear to us at UNSCOM that our initial concerns were soundly backed by fact: Iraq had lied on every level. For example, aerial photographs revealed that Iraq had more mobile launchers than it had declared.

UNSCOM had engaged Saddam in a frustrating game of cat and mouse, trying to hunt down the evidence of Iraq’s wrongdoing. Saddam had covered his tracks well, yet UNSCOM continued to isolate inconsistencies in the stories told by Iraqi officials, pressing so hard on their inherent contradictions that gradually aspects of the truth emerged. Many of these breakthroughs took place over the issue of ballistic missile guidance and control components. Iraq was gradually forced to admit to clandestine dealings with several German and British companies that had provided critical support. But it never revealed the entire truth, just tantalizing bits and pieces wrapped in a cheesy fabric of lies, old and new. Even now Saddam was hiding something and even more so, he was hiding how he hid it. We called this phenomenon "the concealment mechanism” and we were resolved to find out how it worked.

As we made our way north, skirting Kuwait and ascending the fertile valley between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, the briefing was going well. Butler was fired up, and even Duelfer appeared upbeat. He was the pessimist among us. A longtime State Department official, he had risen through the ranks to become a national security!" expert.

…..

|