|

1. PREFACE

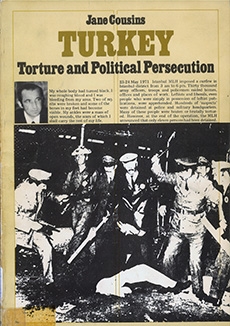

On 12 March 1971 the Turkish armed forces issued a memorandum which resulted in the immediate resignation of the corrupt right wing Justice Party government led by Suleyman Demirel. An ‘above parties’ government wasTormed, pledged to introduce reforms and to put an end to the ‘anarchy’ of the previous two years. On 26 April the military consolidated their political power by declaring martial law in eleven strategic provinces. Twenty months later Amnesty International issued a press statement declaring unequivocally that political prisoners in Turkey were being systematically tortured. Western European journalists had convincing evidence that in these twenty months over 12,000 persons had been detained, arrested or sentenced for political ‘crimes’. According to The Times, the official number of political prisoners awaiting trial before military courts was about 4,000.

On 11 December 1972 the Sunday Times Insight Team published an account of the systematic policy of imprisoning and torturing political opposition in Turkey. This was the first time that any British national paper had tried to present the Tacts. The reason for this silence in the British press is clear. Military censorship of the press in Turkey is strict: no paper is allowed to publish information concerning martial law before an official statement is released. The Martial Law Authorities have the power to close down any paper or magazine which criticizes the regime, and to detain or arrest any journalist, editor or publisher. This power has been used persistently. Almost all the news of Turkey that appears in the British press is provided by two Turkish journa-Ests7~th'emselves subject to this martial law censorship. Apologist for the present Turkish regime, Sami Kohen (Sam Cohen to his British readers) is employed by the right-wing Turkish paper Milliyet. He is stringer for the Guardian, The Economist, the Daily Mirror, the Jewish Chronicle and several American journals. Metin Munir, was until February 1973 editor of the conservative English-language Daily News. He is stringer for The Times, the Financial Times and the BBC. Turkish military censorship effectively censors the British press.

Until late 1972 no British politician had expressed concern about the complete erosion of democracy in Turkey, a NATO and CENTO ally and an associate member of the EEC. When the issue wa raised, notably by Frank Judd, MP, the British Con servative government expressed displeasure at criti cism of the regime. Julian Amery, Secretary of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, told Frank Judd that personally he admired the Turkish regime. Sir Alec Douglas-Home echoed this sentiment in an exclusive interview he granted to Milliyet. Anthony Royle, Under Secretary of State, sounded as if he had been briefed by the Turkish Martial Law Authorities when he claimed, in reply to a letter from Frank Judd, that torture allegations were being manufactured by an East German communist-controlled radio station.

The banning of the Turkish Labour Party, the teachers’ unions and all student unions and the repressive amendments to the constitution provide clearest evidence of the lack of democracy. But it is not easy to discover the exact extent to which the Turkish regime is imprisoning and torturing all political opposition. Turkish government officials, ministry spokesmen and the Martial Law Commanders constantly produce differing figures and dates; a comprehensive list of the names and occupations of those detained or arrested is never released. Press censorship prevents Turkish newspapers from revealing the facts and evidence. The Martial Law Command in the south-eastern Kurdish area of

Turkey is particularly reluctant to reveal information.

It was the lack of information in the British press that led the author to visit Turkey in 'the summer of 1972. In Turkey I was able to meet | politicians, university and school teachers, trade ' unionists and intellectuals on the right and on the > left. I met many persons who had been imprisoned or were awaiting trial for their political beliefs. I also jnet many who had been brutally tortured.

The material in this book has been obtained from Turkish newspapers or has been smuggled out of Turkey. Much of it appeared in a book entitled, File on Turkey, published by Democratic Resistance of Turkey in Europe in 1972. This I have checked and so have other journalists who visited Turkey, who also provided m e with additional material. The Union of Turkish Progressives in Britain (ITIB) has provide d me with information and help. Another source has been Amnesty International. Index provided information concerning the freedom of the press.

The material in this book provides the evidence for the following contentions: that democracy no long er exists in Turkey; that a military regime operates behind a facade of democracy which or too long has either fooled foreign governments or has provided the excuse for supporting an associate member of the EEC, a member of NATO and CENO; that since the declaration of martial law the reime has used the fear of a return to the unrest of 1968-'ll as an excuse for bru ally destroying or silencing all sources of opposition or possible opposition; and that the use of torture is a systematic policy of the regime. As well as the above-mentioned sources of information, I would like to thank the following persons for their help: June Bastable, Mavis MacDonald, and especially Martin Gilbert. Finally, I should like to express my deep gratitude to Alec Horsley who made this book possible.

February 1973

2. Introduction

The history of the modern Turkish state dates from the end of the First World War. After the surrender of the Ottoman Empire at Mondoros in 1918, the Allies planned to divide Turkey among themselves. This scheme was frustrated by a successful national liberation war. Mustafa Kemal is credited with the leadership of the struggle, but its strength was in fact drawn from heterogeneous political elements in Turkey. The first Grand National Assembly met at Ankara in 1920 with Mustafa Kemal as its chairman. Despite the massacre of fifteen communist leaders on the Black Sea, socialists continued to support the nationalist movement and the common goal of independence as ratified by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. In October of that year, the Republic of Turkey was established.

A coalition of the ruling classes and the bureaucracy formed the only legal party, the Republican People’s Party (RPP); it was led by Mustafa Kemal. He was also President of the Republic and assumed the name Ataturk (meaning ‘Father of the Turks’) and the title ‘Eternal Chief’. Until his death in 1938 all legislative, executive and judicial powers were vested in the party and its leader. His government adopted ‘westernization’ as the first article of its programme, and to symbolize the break with the past, the capital was shifted from Istanbul to Ankara. Social reforms were initiated in an attempt to transform Turkey into a modern secular national unit. But in the 1930s the nationalistic element of ‘Kemalism’ became more violent. The ‘sun-language’ theory, that Turkish was the root of all other languages, became official doctrine; Kemalist theoreticians claimed that all humanity descended from the Central Asian Turks. All political opposition, especially from socialists and Kurds, was declared disloyal and illegal.

More broadly Kemalism was, and is, a national-popular ideology which promises a defence of national identity and interests together with painless economic growth under conditions of social equality and justice for all. Such an all-embracing ideal was clearly best personified by an idealized father-figure, Ataturk, whose speeches and writings have become the texts of Turkish political theory. Their basic ambiguity assures their continued centrality. Kemalism may be quoted to justify the prerogatives of the army, the sovereignty of parliament, the primacy of the public sector, the enterprise of the private sector, an evolutionary path of social change and a revolutionary overthrow of injustice. Members of the centre, the right and many of the left all contest the heritage of Ataturk’s political will.

After Ataturk’s death in 1938, his second-in-command Ismet Inonu came to power. He headed …

|